- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Jyotindra Jain

Early Photography In India

Daguerreotype photography, invented in Europe around 1840, came to India the same year and gained instant popularity, so much so that in the following decades India became one of the most prolific producers of photography in the world.

The continuous amalgamation of new technological developments and the intense engagement with the genre by Indian and western photographers working in India in the nineteenth century led to the rise of a complex visual field where photographic technology was put to use in sectors as diverse as the crime branch, hospitals, surveillance, the documentation of people, culture and events to more aesthetically conscious exercises in the sphere of portraiture and the picturesque.

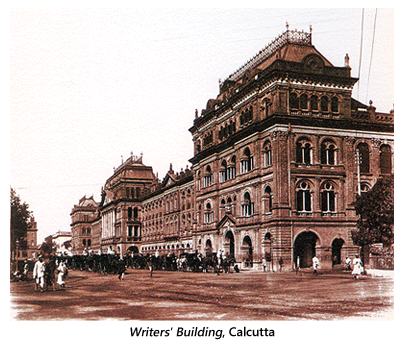

By the mid-nineteenth century, photographic societies and journals had begun to emerge in the cities. The Bombay Photographic Society was established in 1854, followed by the Bengal Photographic Society and the Madras Photographic Society in 1856. These journals became earnest fora for critical discussions of photography. By 1880 several large photographic firms had been established in Calcutta and Bombay.

A vibrant scene of serious photographic practice had already emerged by the time Deen Dayal made his entry into photography in the mid-1870s. Moreover, certain colonlally endorsed aesthetic norms and functions of photography were in place, which Deen Dayal largely imbibed into his work.

Besides its uses in surveillance, photography proved to be an effective tool for the nineteenth century's universal knowledge project - the documentation of the colony's heritage of art, architecture and artisanry, its races, people and natural resources. Deen Dayal became an integral part of this colonial agenda.

From Engraving to Photography

Already in the late 1840s topographic surveys were being replaced by photography on account of its higher 'data-ratio' value. Panoramic views of cityscapes, favourites of surveyors and engravers, were being created by joining together segments of photographs constituting a similar view. One of the earliest examples of this transition was that of Fredrick Fiebig's engraving of the panoramic view of Calcutta from around the late 1840s, which Josiah Row almost literally translated into a photographic version in an eight-part panorama, capturing it from the same vantage point. By this time, most technical institutes in India had introduced photography to their curricula to aid architectural draftsmanship. It was for this reason, at the Civil Engineering College at Rourkee in the 1860s, that Deen Dayal, too, learnt photography.

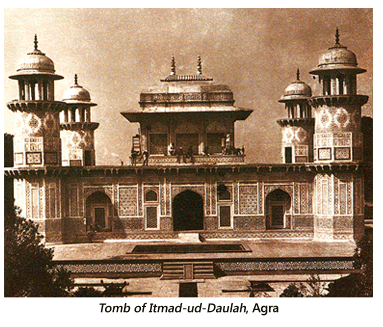

Documenting Heritage

By the time Deen Dayal began work on photographing the famous monuments of Central India as commissioned by Sir Lepel Griffin of the Bengal Civil Service around 1882, certain norms and criteria for photographically recording India's architectural heritage were well established by the work of William Pigou (temples of Dharwar and Mysore region: 1856); Captain Linnaeus Tripe (temples of Madras Presidency: 1856-57); John Murray (the Moghul monuments of the Agra-Delhi region: 1850s and 1860s); and Samuel Bourne (monuments of Agra and Delhi besides others: 1863-1870), to mention only a few. In 1877, James Fergusson famously displayed 500 photographs of Indian architecture at the Paris Exhibition which became exceedingly popular. As a result, some of the research on the subject that followed even prioritised photography over actual fieldwork.

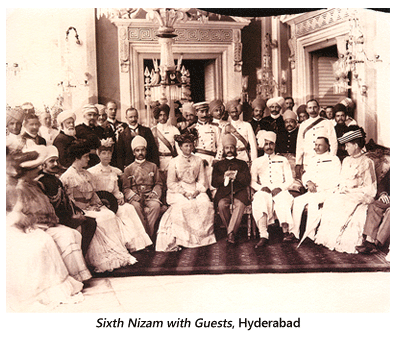

Darbars: Imaging Spectacles of Empire and Princes

Another colonial genre of photography which provided a backdrop to Deen Dayal's work at the court of the Sixth Nizam pertained to the documentation of royal visits from Britain as well as the assemblies/imperial darbars held in India, such as the Viceroy Lytton's Imperial Assemblage of 1876, where 400 Indian princes were invited, or Lord Curzon's Durbar held in 1903. Certain norms set by the British photographers, predominantly concerned with representing the ruler (both British and Indian) with their well-defined hierarchical positioning by including in the frame the spectacular paraphernalia around him, provided Deen Dayal with a working model which he then articulated for the work that he did for the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Portraiture

Besides architectural heritage, the colonial knowledge and surveillance project included the detailed documentation of the 'tribes and castes of India' under the combined rubric of anthropology, census operations, and representation of the Orient. Among a number of these, William Johnson's The Oriental Races and Tribes (1863-66) and J.W. Watson and J.W. Kay's People of India (1868-75) are particularly worth mentioning. Included in the latter category were the "nautch girls" and "beauties" series. Portraits under the broad rubric of the "People of India" were neither participatory nor performative such as the decorous and overstated images of elite portraiture, but instead displayed a frightened and passive "uneasy gaze as they confronted the camera". This passivity of the urban poor, villagers, farmers and tribals entered the aesthetic categories of "the untainted", "the natural" and "the authentic" and from there crossed over to "art" as witnessed by the history of photographic awards from the nineteenth century until recently. The aesthetic canons of portraiture - both of the elite and the vernacular - as established around the time Deen Dayal began work as a studio photographer, served as a frame of reference within the space of which he improvised his individual photographic practice.

Miscellaneous

Other areas of colonial Indian life and culture for which photographic conventions were established before and around Deen Dayal's practice included capturing the picturesque: documenting cities, hill-stations and dockyards; recording religious ceremonies and spectacles, artisans and urban service providers - jugglers and acrobats, military exercises, hunting expeditions, famine relief work, etc. Dayal might have elected some of these as models, but his care for detail and the thick descriptions of the place and people he photographed became evident in his unique personal idiom.

The Article was originally published in the Catalogue titled Raja Deen Dayal: The Studio Archives from The IGNCA Collection (2010)

Images & Article Courtesy: IGNCA, New Delhi