- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Rahaab Allana

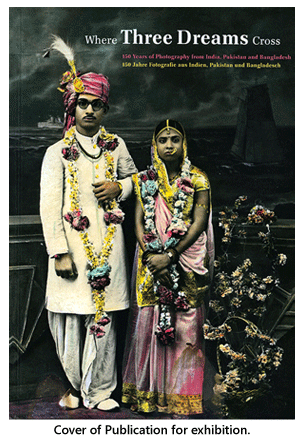

A recent exhibition¹ on South Asian photography, entitled 'Where Three Dreams Cross' sought to highlight indigenous or native photographers from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The exhibition suggests that there is in fact an early history of camerawork that stands outside the ambit of European practitioners in Asia. The exhibition featured over 400 photographs, a survey of images attempting to showcase early trends and photographers from the 19th Century, the social realism of the mid-20th Century, the movements of photography from the studio to the streets and, eventually, the playful and dynamic recourse with image-making in the present.

a survey of images attempting to showcase early trends and photographers from the 19th Century, the social realism of the mid-20th Century, the movements of photography from the studio to the streets and, eventually, the playful and dynamic recourse with image-making in the present.

Cultural practitioners – whether writers, musicians, painters and even photographers – have tried to understand the varied ways in which we should and do look beyond borders; and whether those lines of separation monitor the inner workings and deeper cultures of engagement in our dealings with art, and even curatorial practice that is engaged with expressing its nuances. Consequently, to ponder if early photography in India should geographically encompass Pakistan and Bangladesh, or whether South Asian photography is exemplified by practices in these three nations alone, unfurls a series of assumptions and notions that may counter reasons for the separation of identity today. At the same time, these questions also insinuate how and why there are traceable differences that mark the development of photography in Asia.

The exhibition

Photography in Asia represents the coming of an age, digital, virtual and otherwise. Its history is inextricably linked to a European one, which however, does not find its way into this exhibition. Furthermore, in trying to juxtapose the vintage elements of photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, do these early images comfortably reside by their contemporaries, or are they struggling for space?

Photography in Asia represents the coming of an age, digital, virtual and otherwise. Its history is inextricably linked to a European one, which however, does not find its way into this exhibition. Furthermore, in trying to juxtapose the vintage elements of photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, do these early images comfortably reside by their contemporaries, or are they struggling for space?

The preface in the exhibition catalogue announces: 'This project traces the characteristics of contemporary photography through its historical precedents, revealing the roots.' This is a curatorial decision of working backwards in time, and therefore a significant amount of attention has been given to the self-determination of the curators in creating personal links with the artworks. The catalogue itself marks this intent, with evocative pieces by the curators Sunil Gupta, Radhika Singh, Hammad Nassar, Shahidul Alam, Urs Stahel and Iwona Blazwick as well as Christopher Pinney, Geeta Kapur and Sabeena Gadihoke. The writing however is heavily focused on photography in India, leaving readers a little concerned about tangible practices in the other 2 nations, namely Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Five distinct sections in the exhibition highlight distinct themes that draw the attention of the visitor towards classifications and subjects. These include, the portrait, family, body politic, performance and the street, each highlighting thematic passages. Over 70 photographers including Raghu Rai, Pushpamala N., Rashid Rana, Dayanita Singh, Raghubir Singh, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Gauri Gill, Sheba Chachi Rashid Talukder, Ayesha Vellani and Munem Wasif are presented in the show, with works drawn from important collections of historic photography, including the Alkazi Collection of Photography (Delhi), The Abhishek Poddar Collection (Bangalore), The Udaipur City Palace Museum Archive (Central India), Whitestar (Pakistan) and the Drik Archive (Dhaka). These are joined by many previously unseen images from private family archives, galleries, individuals and works by leading contemporary artists.

Exhibitions are part of a collective enterprise, a space where artists and their work often speak for themselves. Given that India has had a varied encounter with photography over the last 150 years, any engagement with it in the present may consciously undo, abet or seek to trace an evolving narrative of practices.  The bearing of such an exhibition, therefore, highlights three distinct modes of operation that address fraught relationships between past and present: the imperial, nationalist and the post-colonial. These transitions in discursive practices mark continuities, ruptures and contradictions that have given the modern aesthetic in South Asia nourishment in the last 100 years.

The bearing of such an exhibition, therefore, highlights three distinct modes of operation that address fraught relationships between past and present: the imperial, nationalist and the post-colonial. These transitions in discursive practices mark continuities, ruptures and contradictions that have given the modern aesthetic in South Asia nourishment in the last 100 years.

The effect of photography on contemporary exhibition practice, such as that under discussion here, highlights to my mind the framework of the post-colonial (and even post-modern) as the point of engagement with the public. However, in the attempt at shaping the discourses on representation in visual culture today, the true import seems somewhat ruptured, barely addressing the full scope of differences within the exhibition. This is perhaps also because the chief curator (and photographer), Sunil Gupta makes a conscious attempt to avoid what he terms as 'conceptual art' from entering the realm of the exhibition. He broaches on a kind of intended play associated with the notion of heritage, the inherent contradictions that arise from the local to the global, often signaled in the mediations of the South Asian Diaspora, placed in a trans-national landscape of cultural production. However, in questioning 'who produces and for whom and why?', the exhibition struggles to provide an answer.

On the other hand, the exhibition purposefully avoids chronology. There is an emphasis on theme and the use of insinuation and reflection rather than a sense of temporal or even aesthetic progression, or in some cases iconic works featured from the history of the contemporary. Photography is realised as a form of cultural production in the present that lays claim to the past, and this is mediated and transformed by the act of display. Here contemporary practitioners from all countries, respond to cultural dilemmas in varied self-conscious ways and often remain caught in the discrepancies created by colonial history and the paradigms of it. Dayanita's commentary on Mona Ahmed, the personal life of the eunuch who lives beside a graveyard; Pushpmala N.'s engagements with the historical archive and the use of iconcity; the use of memory by Vivan Sundaram through a relay of works on his aunt and grandfather, Umrao Sher Gil; these are only some of the links created that provide insights into the history of the contemporary.

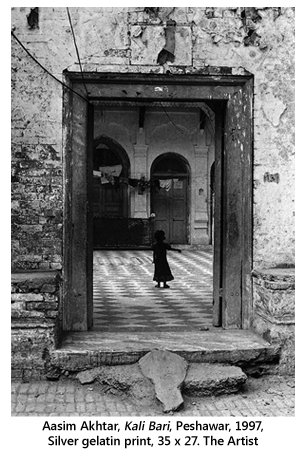

Hammad Nassar, curator of the collections  from Pakistan, in the catalogue essay highlights the infusions of fine art and documentary photography that emerges from Pakistan. Nasar is a London-based curator, gallerist, writer and co-founder of the arts organisation, Green Cardamom, with a range of interests outside photography. He comments on the magic realism of some of the ruh khitch (soul pulling) photographers who line the streets of Lahore with older cameras. Important examples here are Gogi Pehewan and Muhammad Amin. Iftikar Dadi and Shaukhat Mehmood's interaction with photography is of interest in connection with the genre of manipulating and altering the surface of the image, as one sees in painted photographs. Bani Abidi's work, represented in video and photographic forms, together with Rashid Rana's investigation of photographic narrative structures creates an interesting juxtaposition with photographers in India, depicted through nuanced investigations of place and identity.

from Pakistan, in the catalogue essay highlights the infusions of fine art and documentary photography that emerges from Pakistan. Nasar is a London-based curator, gallerist, writer and co-founder of the arts organisation, Green Cardamom, with a range of interests outside photography. He comments on the magic realism of some of the ruh khitch (soul pulling) photographers who line the streets of Lahore with older cameras. Important examples here are Gogi Pehewan and Muhammad Amin. Iftikar Dadi and Shaukhat Mehmood's interaction with photography is of interest in connection with the genre of manipulating and altering the surface of the image, as one sees in painted photographs. Bani Abidi's work, represented in video and photographic forms, together with Rashid Rana's investigation of photographic narrative structures creates an interesting juxtaposition with photographers in India, depicted through nuanced investigations of place and identity.

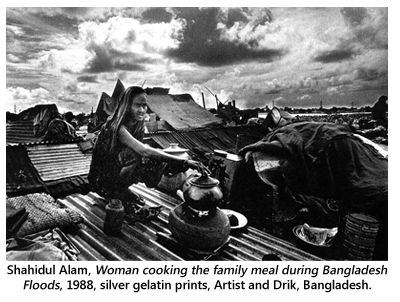

Here we take an interesting turn to Bangladesh, an important force in photography today, curated by Shahidul Alam, a pioneering figure in the oganisation and dissemination of photography in Bangladesh. Shahidul Alam studied and taught chemistry in London where he obtained a PhD from the University of London, starting out as a practitioner of photography in 1980. In 1989 he set up the Drik picture library and Pathshala: a South Asian Institute of Photography. He is also a director of Chobi Mela, the well-known festival of photography in Asia. In this exhibition, he brings forth the work of Golam Kasem Dady, an early photographer in Bangladesh in 1918. Later works by Rashid Talukdar who photographed perhaps the most important moments of the 1970s, juxtaposed with images of Muhammad Shafi or Jalalluddin Haider create a political trajectory that permits a deeper understanding of Bangladesh's violent past. Other younger and extremely dynamic photographers from Bangladsh on display were Shumon Ahmed, Abir Abdullah, Abdul Hamid Kotwal and Munem Wasif.

Frictions

Historical material in the exhibition is rarely seen as a starting point but rather, as a point of return. In taking this view, the vintage material seems somewhat appropriated to the production of material in the contemporary, rather than a point of initiation. There seems to have been an act of scrambling the images, perhaps a rightful solution in this case. Material is drawn from disparate collections and the thematics identified are often from older productions or exhibitions. The method devised to deal with this problem is to let the images speak for themselves. This is an important curatorial stance, but needed to be sussed out in more tangible and descriptive ways, allowing the unread viewer to take stock of the movements and international conditioning in photography in Asia.  The impressionistic overview veers through the tracts of self-representation, portraiture, documentation and artistic recreation, where artists from the three countries try to contend with their own realities and, in doing so, they yearn to be understood.

The impressionistic overview veers through the tracts of self-representation, portraiture, documentation and artistic recreation, where artists from the three countries try to contend with their own realities and, in doing so, they yearn to be understood.

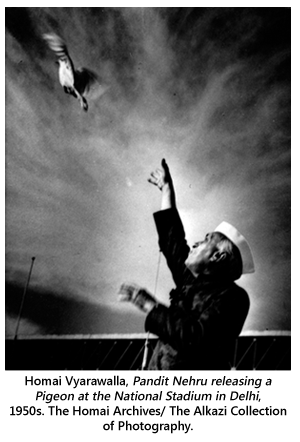

From a holistic point of view, exhibitions such as these are an interesting route into Art History. Here the social economic and, at times, political forces that shape artistic production and distribution come together, exerting varying degrees of pressure on artists, critics, curators, collectors and dealers alike. Therefore, while encountering the exhibition, it becomes important to forge your own links with the works. How, then, does Muhammad Arif Ali with his 2008 works of political rallies compare with the sweeping panoramic images of Praful Patel in Mumbai in the 1950s? This leads us to compelling historical figures such as Homai Vyarawalla and Kulwant Roy, mirrored on a facing wall with architectural images by Lala Deen Dayal from the Alkazi Collection and by Bharat Sikka's gigantic views of contemporary Delhi.

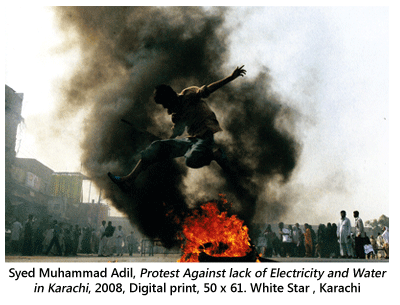

Rooms of wonder yield the dynamic images of Vikas Roy, Ram Rahman and Abdul Kalam Azad, leading further onto Muhammad Ali Salim, and even views by Shahid Datawala. Further connections may be drawn between Syed Muhammad Adil and Tanveer Shahzaad, while the historical images of Bozai go well with Homai Vyarawalla and Whitestar images from Pakistan. Therefore in exhibitions such as this one, it is important to identify why the juxtaposition of the old and the emerging, have led artists to confront the future of their own productions with varying degrees of emulation, rejection and creative departure.

Apart from talks by the three main curators, a compelling symposium was organised over two days in the Fotomuseum, Winterthur. The speakers included curators such as Pramod Kumar KG, who spoke on the life of portraiture in India, based on his extensive work in the Udaipur Archives. Akshaya Tankha and Suryanandini Narain revealed their experiences of ethnography and the archive and the representation of women in studio photography, respectively. Practitioners such as Dayanita Singh and Bani Abidi spoke of their personal inspirations and experiences  that led to the generation of their work. Sabeena Gadihoke highlighted her interest in photography during and after the national movement in India, concentrating on press and magazine photography. One of the most intriguing talks was by independent practitioner and senior assistant editor for the Telegraph, Aveek Sen, on his personal journey through the images and themes that underlay the exhibition and the complexity between the meaning and resonance of images and words.

that led to the generation of their work. Sabeena Gadihoke highlighted her interest in photography during and after the national movement in India, concentrating on press and magazine photography. One of the most intriguing talks was by independent practitioner and senior assistant editor for the Telegraph, Aveek Sen, on his personal journey through the images and themes that underlay the exhibition and the complexity between the meaning and resonance of images and words.

In all, the exhibition presented more than pure aesthetic delight, creating horizons of contestation between themes and images. In a world where the art market seems to be sky rocketing and artists are becoming ever more demanding of galleries and curators are vying to represent them – photography in Asia still seems to demand much greater academic input and real substantive criticism that would allow it to represent more than regional identity. Such an interaction would necessarily explain and exploit a landscape that has a powerful modern visual paradigm in order to highlight a sense of cultural difference in the 21st Century, a sense of heterogeneity in what is 'seen' and experienced. This is the world that contends with ideas of global capitalism, citizenship, neo-imperialism, minorities, exile, secularism: and these are the boundaries that need to be transgressed for a deeper understanding of history and the contemporary.

Note

¹The exhibition 'Where three dreams cross: 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh was on display at the Whitechapel Gallery, London in January 2010 and at the Fotomuseum in Winterthur, Switzerland from June until August 2010.

The article was written for the IIAS Newsletter, & was published in the Autumn Issue, 2010