- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Through the Eye of a Lensman

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

A Conversation between Saba Gulraiz and Pablo Bartholomew

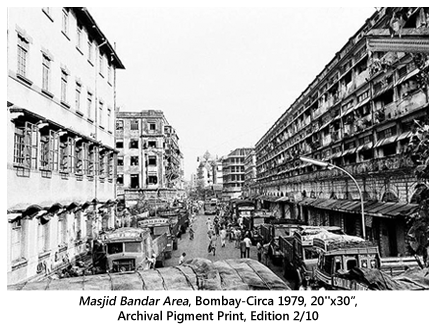

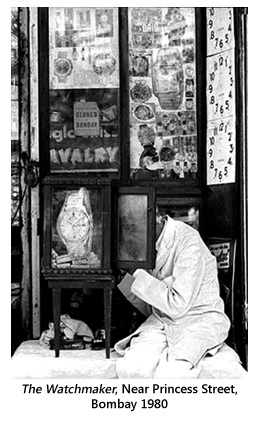

“A good photograph can stop time and awaken distant memories”, believes Pablo Bartholomew, a leading photographer of India. Photography, for Pablo, is not just a craft. It is a passion; an 'inner urge' to capture all that is vulnerable to the vagaries of time and memories. Early in his teenage, this inner urge drew him to documentary photography. These works convey different emotional states and associations. They give access to his own internal space. In the early phase of his career, as a photojournalist, he would just hold his camera and wander in the lanes and by-lanes of the big cities like Bombay and Calcutta, in search of something that he would call a 'visual joy'.  These experiences as a photojournalist in different parts of the country added a new dimension to his art of photography.

These experiences as a photojournalist in different parts of the country added a new dimension to his art of photography.

Now his camera not only beholds the memories of his past; but the images are also meaningfully held between the past and the present, the sombre shades of life. His camera clicks to capture ordinary everyday sights and occurrences. Many of these images give a peek into broader concerns of life where his anonymous characters are representatives of a world located on the periphery. Such images can be read as a critique of contemporary life but the situations sometimes fuse with them to create humour, an element typical to Indian life. Pablo accomplishes this juxtaposition masterfully and sensitively.

Saba Gulraiz: I would like to open this interview with a line from your father's poem “All things stand naked in the house of the eye.” (-Richard Bartholomew, an eminent art critic, photographer and poet) How beautiful, how ugly, and how strange do you feel the naked realities that engage you as a photographer/photojournalist are?

Pablo Bartholomew: These are all parts of life of a photographer that engages and lives and works with photography that is real and tangible.

By real and tangible I mean that the photographer engages with people and looks at real life situations.

It would be different for a photographer creating conceptual work.

SG: You took up photography as a passion and then it turned into your profession. What do you enjoy more – photography as a passion or as a profession?

PB: In whatever you do, the passion has to be there. Having said that there are levels of passion and the deepest is from the work that I do for myself.

SG: You initially started out as a documentary photographer and your early works are black-and-white. What particularly attracted you to black-and-white photography? Now being a photojournalist you have to turn to colour. Do you have any regrets about renouncing your black-and-white world?

PB: I haven't renounced the black-and-white world at all… There are many ways of working with it. I still shoot some things in black-and-white. I have been working with my archive and two major shows out of it. I have done my father's exhibition and book.

So I am very much working with black-and-white.

In the 70's there was no colour as such and mostly everything was black-and-white so that was the medium that one took to. And when I shifted to working in the photojournalistic medium by 1983, the magazine world had started to move and change into colour pages. Hence I started to shoot a lot of colour.

SG: Over the years the world has seen a remarkable transition in everything, including the modes and techniques of photography. Now with the coming of digital cameras and Photoshop, the possibilities of photography to be used as an art form have expanded tremendously. How far have you assimilated these changes in your own style of photography?

SG: Over the years the world has seen a remarkable transition in everything, including the modes and techniques of photography. Now with the coming of digital cameras and Photoshop, the possibilities of photography to be used as an art form have expanded tremendously. How far have you assimilated these changes in your own style of photography?

PB: For me there is no difference in the technique. When working with digital material, Photoshop is like the digital dark room. I do not manipulate images and cut and paste things in. That sort of work does not appeal to me at all.

It is too easy to make that sort of creation. And too many artists have abandoned their tools to take up this very easy route of creation.

SG: In one of your earlier interviews you have said that bad light has a world of drama. What is this drama? How does bad light capture this drama?

PB: It is about the shadows and highlights. And when you have great low key images, the shadows speak. That is the magic of bad light.

SG: Your subjects have always been the underdogs like rag pickers, film extras, and prostitutes living in urban landscapes. How do you see this “urban India in transition” through your lens?

PB: I don't see a transition. I just capture the essence of a period and an era.

SG: Your images are not just images, they are the narratives of the bygone days. There is a kind of nostalgia, a tinge of melancholy or emptiness in these images….

PB: Mostly the images are a document, a record of an era. But they are not merely documents, they have feelings, thoughts and aesthetics. I don't think it borders on nostalgia. Obviously anything that is a few decades old has some sort of time warp but that is not why the pictures become exciting. Yes there is emptiness as the world then was less crowded but all these stand out and still stand the test of time and are very fresh.

SG: I am interested to know about your two recent exhibitions, Outside In: A Tale of Three Cities and Chronicles of A Past Life: 70s & 80s.

PB: “Outside In” was an exhibition of black-and-white photographs I had taken in the year between 1970s and 80s. It was exhibited at the National Museum, New Delhi and Fotomuseum Winterthur (Zurich) Switzerland. It has my experience of the lost generations of Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta of the 1970s and 1980s. “Chronicles” is my diary, of when I was growing up, between the age of 15 and 25. It's my earliest work; I photographed my family and friends.

SG: The theme in your series of works like Indians in America, The Indian Émigré, Indians in France is migration. Is this because being the son of immigrant parents you also had to face the crisis of identity and alienation?

PB: Yes you can assume this. It gives me a reason to look at others lives and also provides an excuse for me to travel.

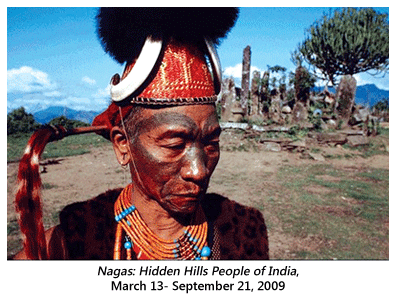

SG: While doing a series of photographs on the Naga tribes of Northeast India you had done intensive research on these tribes living in a marginal world. Is research also a part of your photography practice? Does it enhance the reality of your subject or add meaning to it?

PB: I don't think the Nagas live in a marginal world. It is Indian politics that has marginalised most of the North Eastern part of the country. Yes, research is very big part of my life and as I say this, I am in Leicester in the UK researching and photographing.

SG: There are certain memories/images that we would like to erase from our mind. One of such images is the image of a half buried dead child for which you won the World Press Photo Award of the year for the Bhopal Gas Tragedy (1984). At that time I was a small child and only have a faint remembrance of the horrible gas tragedy in Bhopal, the place I belong to, but this image still haunts me, it's so painful. Would you like to share your experience of the whole tragic situation? What is more important for you–the 'news value' that a calamity carries with it or the very reality itself?

b No, I would not like to erase this memory of Bhopal. But there is a shame and guilt associated with winning an award and then seeing how marginalised these people have been made by the endless suffering that they had to go through. Maybe there will be a time when I will do something in Bhopal again.

Photos Courtesy: Pablo Bartholomew