- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

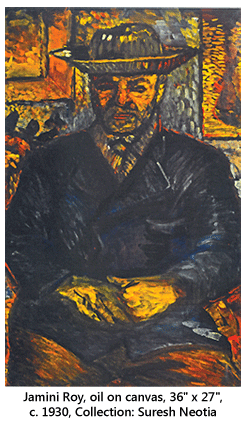

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

A time to Act

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

Hard Talk

Shoma Bhattacharya in conversation with Suresh Neotia

There is no lovely lady in New Delhi's designer circuit going gaga over a glorious miniature or a broken bronze of a pre-AD era. Yes, she would call over her band of sundry beauties and their powerful husbands to show off her latest Subodh Gupta acquisition, glinting away in an already resplendent den, screaming money and status. But, no, she is unlikely to spare a second glance for what classifies as national heritage, as India's history.

There is no lovely lady in New Delhi's designer circuit going gaga over a glorious miniature or a broken bronze of a pre-AD era. Yes, she would call over her band of sundry beauties and their powerful husbands to show off her latest Subodh Gupta acquisition, glinting away in an already resplendent den, screaming money and status. But, no, she is unlikely to spare a second glance for what classifies as national heritage, as India's history.

These may not be the exact words of Suresh Neotia, a respected figure in the world of Indian antiquities. But they more or less convey his frustration at the current state of affairs in his chosen field antiquities and art treasures. A collector himself, rather a former collector, the corporate elder is now a somewhat bitter critic of the government's cultural wing, which is nominally in charge of preserving the country's heritage. Neotia's bitterness, however, has not frayed his passion nor chipped his determination to carry on fighting for what he loves and knows best.

“I don't mind going on record as saying that Jawahar Sircar, the culture secretary, also my very dear friend, does not match his words with deeds. Of course he is an extremely cultured and cultivated man, well qualified for his post, but…” Neotia trails off. Neither does he has a very high opinion about the current Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972, which came into effect from April, 1976. “This Act has stopped dissemination of interest in Indian antiquities among scholars, collectors and in turn in dealers. So the dealers have all gone underground,” he says.

“My concern is that in the last 35 years, very few scholars have emerged in the field of antiques. The only young expert I know is Naman Ahuja, a professor in Delhi's Jawaharlal Nehru University. There is almost no one to replace the likes of Pramod Chandra, Pratapaditya Pal or B.N. Goswami,” he says. So, if in the remote future, the government decides to constitute a watchdog body for authenticating antiques, it will have a mission impossible in its hands.

“If anyone seeks to buy a piece of British heritage, that person is legally required to notify the government. Once notified, the government buys it to prevent that bit of history from leaving the national boundaries. In China, there is a system of exemption of duties, which has inspired the Chinese nouveau riche to import large chunks of their national riches back to their homeland,” says Neotia. Then he returns to what also becomes our favourite refrain throughout this exchange: “So what is our government doing about this?”

To its credit, like any other organization, the central government did form a committee under the chairmanship of Professor R.N. Mishra to look into recommendations for modifying the flawed 1972 Act. The members met a few times and failed to agree on most points, leading to absolute inertia. Neotia too had been appointed a member, all the reason for his acute disappointment with the failure of the body of experts to make some decisions.

How it started

Though there was an Act The Antiquities (Export Control) Act, 1947in place, the Indian antiques market was an unregulated zone. Unaccounted money drove the market, with buyers and sellers exchanging cash for priceless objects. Smuggling and fraudulent dealings were rampant. Worse, vandalism at archeological sites and public places had gone viral. Terracotta and bronze sculptures would be looted and efficiently spirited out of the country in large numbers by a clandestine network of dealers. Adding to the government's angst was talk about the impending sale of the Nizam's jewels to buyers abroad. All this set off a sudden spurt of action. “Indira Gandhi almost acted in panic. An Act was swiftly drafted in 1972,” Neotia says. “Ultimately, her babus drafted such a statute that it smothered any buyer interest.”

Though there was an Act The Antiquities (Export Control) Act, 1947in place, the Indian antiques market was an unregulated zone. Unaccounted money drove the market, with buyers and sellers exchanging cash for priceless objects. Smuggling and fraudulent dealings were rampant. Worse, vandalism at archeological sites and public places had gone viral. Terracotta and bronze sculptures would be looted and efficiently spirited out of the country in large numbers by a clandestine network of dealers. Adding to the government's angst was talk about the impending sale of the Nizam's jewels to buyers abroad. All this set off a sudden spurt of action. “Indira Gandhi almost acted in panic. An Act was swiftly drafted in 1972,” Neotia says. “Ultimately, her babus drafted such a statute that it smothered any buyer interest.”

A mountain of red tape, it seems, confronts the potential antique buyer. The mandatory registrations, documents and photographs that have to be submitted to the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) may not seem too unreasonable to the objective layperson. However, the following example cited by Neotia leaves none in doubt about the futility of governmental procedures. “If I move an antique sculpture from my living room to my dining room or from my Delhi house to my Kolkata home, I will have to inform the ASI about it. An officer from the local ASI wing is empowered to inspect my home for such 'movements' at any time. If I somehow forget to keep the ASI informed, I am liable to be prosecuted,” Neotia elaborates, possibly from personal experience.

He adds: “Between 1940 and 1970, several large collections were put together. Post the Act, there has been no sizeable collection. Most of the domestic trading, if any, takes place at a clandestine level. Looting from archeological sites also continues. There is an archeological site in Chandraketugarh, around 50 miles from Kolkata, where figurines and objects dating to the first and second centuries BC have been unearthed. Any object in relatively good shape finds its way abroad via the smuggling route. This is happening today and now. Such is the state of security that any local person can use his ingenuity to pick up a first BC figure and sell it off to a dealer who then makes a killing abroad.”

Now what?

Precisely, I ask Neotia, what would be his specific suggestions to the government to break out of this vicious cycle of no-buyer-no-seller-no expert-no culture in the matter of antiquities. His solution: “First, the government's police wing has to get serious about catching the smugglers. This will at least send a signal to the thieves. Second, free the trade. There are no restrictions on trade in other objects, so why on antiquities? The government should stop interfering and controlling, period.  The gold control order was scrapped which curbed gold smuggling to a great extent.”

The gold control order was scrapped which curbed gold smuggling to a great extent.”

But wouldn't that be rather simplistic? Antiquities, after all, constitute our national heritage. Safeguards have to be put in place. The government has to be in charge when the word, 'national' comes into the picture. There has to be a watchdog which will vet the antiques. There have to be experts and scholars, there has to be schooling. There has to be an infrastructure which will prevent daylight robbery in archeological sites and then the subsequent smuggling.

“Absolutely,” says Neotia. “But we have to make a start somewhere. The 1972 Act was passed in Parliament by Indira Gandhi's government to prevent smuggling that had become rampant. But those who wrote the contents of the Act worsened the situation to such a degree that since 1976, not a single sizeable antique collection has been put together by an individual.” Give or take a Vijay Mallya or a Shiv and Kiran Nadar, both of whom have imported substantial numbers. In both instances, personal clout and friends in high places have played their role in granting of requisite exemptions and smoothening of creases.

“The maximum we have managed to extract from this government is an exemption of duties on objects provided they are meant for public display.” Decoded, an antique buyer will not have to pay a duty only if he/she declares that the antiquities being imported are meant for public display at a public museum or a national institution.

But how about the body of individual buyers who collectively add to the market's strength? What if I, a common citizen with no vocabulary of clout, want to buy a piece of antique just for the love of it. Who do I approach? “No one. Just no one,” Neotia tells me bleakly.