- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

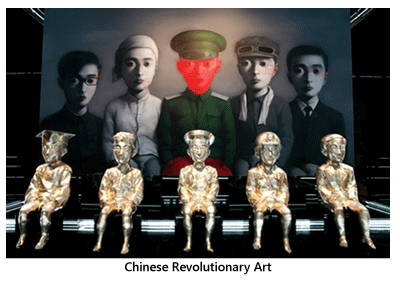

Dragon boom or bubble?

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

Market Insight

by AAMRA

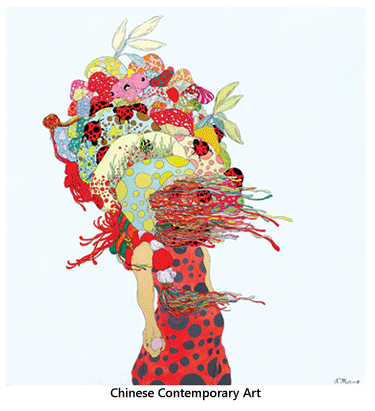

On March 14, Bloomberg reported that China has overtaken the U.K. to become the world's second-largest art market after the U.S. Now that is old news, on which we have already touched upon in the last issue.  Art Tactic's Chinese Contemporary Art market report 2011 stated that, “China and its contemporary art market have gone through a remarkable transformation in the last 5 years. The contemporary Chinese auction market has grown from just below $1 million in 2002 to $167.4 million in 2010, and this year is already set to become a record year…

Art Tactic's Chinese Contemporary Art market report 2011 stated that, “China and its contemporary art market have gone through a remarkable transformation in the last 5 years. The contemporary Chinese auction market has grown from just below $1 million in 2002 to $167.4 million in 2010, and this year is already set to become a record year…

The global art market recovery has been helped by strong economic growth in Asia. Sotheby' and Christie's Hong Kong have seen sales turnover increasing by 300% between 2009 and 2010. Mainland Chinese auction houses such as Poly and Guardian have seen their Chinese sales seasons grow from $397 million in 2009 to $2.2 billion in 2010, and even the contemporary Chinese art market is approaching the previous peak level set in 2008.”

But while everybody else in the world seems to be bullish and full of hope about the rise of China, an art analyst and critic, sitting in Sydney has raised a very valid question. In his blog, Artmarketblog.com, Nicholas Forrest writes:

“What concerns me most about the Chinese art market is the fact that the Chinese are not only showing a keen interest in the work of modern master “trophy” artists, just as the Japanese did, but unlike the Japanese are also showing a keen interest in the work of their own young contemporary artists. The first reason that this is concerning is the obvious issue of inflated pricing that arises when uneducated and indiscriminate buying of “trophy” works takes place especially when the reasons for purchases are related to status, vanity and games of one-upmanship. The second reason that this is concerning is that China does not have the sort of private gallery infrastructure in place that is needed to support young contemporary artists and nurture their careers over the long term. Without the private gallery step in the process of natural progression, young artists end up being thrust into the limelight ill-prepared and without having been through that crucial process of critical review that the private gallery system is a major part of. It is that private gallery system that would usually separate the true stars from the posers and direct the marketplace towards the true stars. Artists whose work is taken directly from the art school to the auction house are essentially being thrust into a position of authority and responsibility without the proper credentials. This is fine while the going is good but as soon as the money runs out and these artists are asked to prove their worth the whole foundation that their career has been built on comes tumbling down.”

The second reason that this is concerning is that China does not have the sort of private gallery infrastructure in place that is needed to support young contemporary artists and nurture their careers over the long term. Without the private gallery step in the process of natural progression, young artists end up being thrust into the limelight ill-prepared and without having been through that crucial process of critical review that the private gallery system is a major part of. It is that private gallery system that would usually separate the true stars from the posers and direct the marketplace towards the true stars. Artists whose work is taken directly from the art school to the auction house are essentially being thrust into a position of authority and responsibility without the proper credentials. This is fine while the going is good but as soon as the money runs out and these artists are asked to prove their worth the whole foundation that their career has been built on comes tumbling down.”

Forrest here raises a very valid point. Because the Chinese pattern is very like the American pattern before the global meltdown. Actually, the way a nation's art market performs can also be understood by the way the same nation's property market performs. And China's property market, in its own way is not in the pinkest of health. Like all nations which try a simulated boost on their economy, China is building massive cities in anticipation of the massive rise in the number of Chinese people who can afford to purchase their own home. This, the Chinese government believes will take place. The problem is that many of these cities remain empty a long time after construction has been completed. Moreover, they offer no signs of filling up.

A recent article in Bloomberg stated, “China's property market may be heading into a bubble as the economy's reliance on real estate reaches a level close to the housing peaks in the U.S. and Japan, according to Citigroup Inc.” This is particularly relevant and as Forrest rightly points out, this “compares China's property market boom to the Japanese property market peak the collapse of which caused the art market collapse of the early '90s. With so much money being invested in property and being made from China's property boom it is highly likely that a significant proportion of the money being spent by the Chinese on antiques and fine art comes from the property boom. It is therefore also highly likely that the ability to pay any debt that Chinese buyers are racking up to pay for their trinkets is reliant on the continued positive progression of China's property boom.”

Now this is a very alarming supposition the Forrest makes. If it is true that the money being pumped into the Chinese art market is actually being channelised from the property market, there is every possibility that the 2008 trend in the Chinese art market will be repeated there.  If property dealers fail to get their customers, it will have an adverse effect on the economy, whereby the economy will suffer having a direct impact on the art market boom.

If property dealers fail to get their customers, it will have an adverse effect on the economy, whereby the economy will suffer having a direct impact on the art market boom.

In fact, Forrest's research also reveals a few disturbing facts about the performance of Chinese buyers in the global art market. He writes:

“If you follow the progress of the art market you will be aware the auction houses have experienced serious problems when dealing with a number of Chinese buyers whose actions threaten to stifle the surge of Chinese buyers before it has really even begun. As reports of Chinese buyers failing to pay for antiques and fine art that they have purchased at auction continue to hit the headlines, auction houses have been forced to take action. Several major auction houses have chosen to combat the issue of non-payment by asking clients who are bidding on certain high priced lots to provide a refundable deposit before the auction takes place. This may seem like a simple and neat solution to the problem, but such a scheme is likely to cause conflict between the auction houses and Chinese buyers who are used to conducting business in a particular social and cultural environment…

It is important to know that non-payment by Chinese buyers is not something that has only just started happening. In fact, there are reports as far back as 2007 that express concerns over the number of instances of Chinese buyers failing to pay for art and antiques that they had purchased at auction. Since 2009 there have been an increased number of reported instances of non-payment by Chinese buyers culminating in the recent clampdown by auction houses on delinquent buyers. Excuses for non-payment or slow payment range from problems (of) transferring money into Western currencies to issues with the “legal” status of objects. Many instances of non-payment, however, appear to just be the result of plain old overzealous bidding.”

Forrest goes on to list a few instances of non-payment:

-

Political statement: There have been instances where Chinese buyers have bid on items that were allegedly looted from Chinese sites then refused to pay as a political statement. The most infamous case of politically motivated non-payment is that of dealer Cai Mingchao and the bronze animal heads which Cai purchased at the Yves Saint Laurent/Pierre Berge sale in 2009 then failed to pay for citing evidence that the items had been illegally removed from China as his reasons for defaulting on payment.

-

Buyers remorse: With many Chinese buyers paying way over the odds for antiques and fine art, it is likely that at least some of them will go away from the auction regretting the amount that they spent.

-

Unable to pay: Once again, overzealous bidding from determined Chinese bidders who do not want to “lose face” by losing an auction is likely to produce instances of buyers bidding beyond their means.

-

Negotiation tactics: It is likely that some Chinese buyers will not see the final auction price as the end of the sale and will begin negotiating with the auction house over the price as well as terms of payment once the sale has ended.

-

Currency exchange: Apparently it takes considerable time to transfer money out of a Chinese account and to perform the necessary currency exchange when purchases have been made outside China.

It is true that the number of instances of slow payment and non-payment have been very small, however, the issue is not so much how many instances there have been, but what the ramifications have been for the industry and for the sentiment of Chinese buyers. It is no secret that respect and honour are a big part of Chinese culture. Not wanting to “lose face” on such a public stage, Chinese bidders are likely to feel strong opposition towards the implementation of enforced deposits by several auction houses. To be asked to provide a deposit will potentially offend Chinese bidders who will see such a demand as disrespectful and offensive, because to be forced to pay a deposit suggests that the bidder is untrustworthy. If you think that demanding a deposit will not have an effect on auction proceedings then you might like to consider the poor results of the recent Meiyintang Collection auction that was held at Sotheby's in Hong Kong which an article from Bloomberg suggests could be the result of required deposits for “premium lots”.

It is no secret that respect and honour are a big part of Chinese culture. Not wanting to “lose face” on such a public stage, Chinese bidders are likely to feel strong opposition towards the implementation of enforced deposits by several auction houses. To be asked to provide a deposit will potentially offend Chinese bidders who will see such a demand as disrespectful and offensive, because to be forced to pay a deposit suggests that the bidder is untrustworthy. If you think that demanding a deposit will not have an effect on auction proceedings then you might like to consider the poor results of the recent Meiyintang Collection auction that was held at Sotheby's in Hong Kong which an article from Bloomberg suggests could be the result of required deposits for “premium lots”.

Forrest's argument is solid. However, there is one small loophole. If it Is so that most of the money being channelised into the art market by Chinese bidders is a result of the property boom, and it IS also true that the cities being built by the Chinese government are remaining unpopulated long after being constructed, the question is where is the money in the hands of the Chinese bidders coming from? If we are to suppose that all the construction work is being carried out on speculation, and also that when it is coming to Chinese auction houses in the mainland, no money is actually exchanging hands, and the whole transaction is being carried out on a virtual scale, then of course it makes sense. The niggling feeling is that Chinese bidders have failed to pay up on certain occasions, when it came to international auction houses. Which reinforces the idea that the money, in currency notes, perhaps is still to see the light of day. And that is something to be thoughtful about.

However, it would only be good if Forrest's supposition and alarm bell is proved to be wrong. Because that way, the global art market will stand to gain from the Chinese boom.