- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

by Soumik Nandy Majumdar

'The artists and art-connoisseurs of our past used to set rules and defy them too. … To loose the cultural wealth of our past is a tragedy indeed, but to have only those and nothing from the present is also not a conducive situation for the sustenance of art. … We might hope to expand our art feeding on the past, but this will not work as long as we eschew the present'

Abanindranath Tagore. 1

Abanindranath Tagore (1871- 1951) is not only one of the most significant artists of twentieth century India but he is also a kind of enigma to the art-knowing public. His cult status in modern Indian art has often overshadowed the originality of his contribution. Even a cursory look at his complete oeuvre reveals that it is well-nigh impossible to see his art entirely either in the model of a linear chronological progression or within the confines of specific stylistic genre. Any attempt to rethink or re-assess Abanindranath Tagore, as Ella Dutta writes, 'is a task riddled with ambiguity. Is he to be seen as the founder of a new school of painting, the Bengal School? Do we take into account his links with the nascent nationalist movement? Or do we only consider his achievements as an artist?' 2

Abanindranath Tagore (1871- 1951) is not only one of the most significant artists of twentieth century India but he is also a kind of enigma to the art-knowing public. His cult status in modern Indian art has often overshadowed the originality of his contribution. Even a cursory look at his complete oeuvre reveals that it is well-nigh impossible to see his art entirely either in the model of a linear chronological progression or within the confines of specific stylistic genre. Any attempt to rethink or re-assess Abanindranath Tagore, as Ella Dutta writes, 'is a task riddled with ambiguity. Is he to be seen as the founder of a new school of painting, the Bengal School? Do we take into account his links with the nascent nationalist movement? Or do we only consider his achievements as an artist?' 2

Quite unusual to his time, Abanindranath Tagore's art abstains from any kind of straight-jacketing and it is replete with surprises, unforeseen turns and twists and often amazingly new ideas nearly unsettling his previous ones. His alignment with the Swadeshi pledge and his engagement with the so-called revivalist school are equally complex and frequently confronted by his own sensibility and predilections. His literary outputs too bring to light the same kind of propensity.  The Bengali readers are still charmed by his extraordinary ability to turn a commonplace descriptive style of writing into a vivid, sensuous and emotive experience. He does that not by any definitive stylistic search but largely by infusing his writing with his curious responses to the cultural and social reality around and by throwing his art open to a vast range of sources from traditional allusions to contemporary dialects to urban witty ones. Passing through the mesh of his personal sensibilities all these features eventually claim the writer and painter Abanindranath as one single but multifarious personality who 'writes art' and 'paints words'.

The Bengali readers are still charmed by his extraordinary ability to turn a commonplace descriptive style of writing into a vivid, sensuous and emotive experience. He does that not by any definitive stylistic search but largely by infusing his writing with his curious responses to the cultural and social reality around and by throwing his art open to a vast range of sources from traditional allusions to contemporary dialects to urban witty ones. Passing through the mesh of his personal sensibilities all these features eventually claim the writer and painter Abanindranath as one single but multifarious personality who 'writes art' and 'paints words'.

However, it is not an easy task to take Abanindranath Tagore out of history and evaluate his works independent of the prevalent historical developments of pre-independent India. While it is not altogether unjustified to recognize him as the protagonist of the Bengal School painters but to fetter him to this particular category will certainly lead to an absolutely incomplete appraisal of his works. While addressing the inherent difficulties of retrieving Abanindranath from the continual stereotyping Tapati Guha-Thakurta writes, 'How effectively can we pull the artist out  of his nationalist past and the folds of the Indian art injunctions, however profound they seemed to be, and privileged individual experience along with a fresh reading of the past. Much later in 1924, in a letter written to Dhirendra Krishna Deb Burman, Abanindranath cautioned against a mindless derivation in the name of salvaging Indian art. He wrote, 'This thing called Indian art the more I see this the more I get convinced, that what is brought forth in music, painting or sculpture in this way is burglary committed on one's own or other's treasures. They are stolen goods we want to trade off as our own.' 7 He further wrote, “Remember I cautioned Nandalal before all of you, the other day, whether you take after Ajanta or Greek or Japanese or China, it is nothing but taking to another man's way. Why should I port my boat at an alien coast when each one of us has our own? We have no option but to go alone.” 8

of his nationalist past and the folds of the Indian art injunctions, however profound they seemed to be, and privileged individual experience along with a fresh reading of the past. Much later in 1924, in a letter written to Dhirendra Krishna Deb Burman, Abanindranath cautioned against a mindless derivation in the name of salvaging Indian art. He wrote, 'This thing called Indian art the more I see this the more I get convinced, that what is brought forth in music, painting or sculpture in this way is burglary committed on one's own or other's treasures. They are stolen goods we want to trade off as our own.' 7 He further wrote, “Remember I cautioned Nandalal before all of you, the other day, whether you take after Ajanta or Greek or Japanese or China, it is nothing but taking to another man's way. Why should I port my boat at an alien coast when each one of us has our own? We have no option but to go alone.” 8

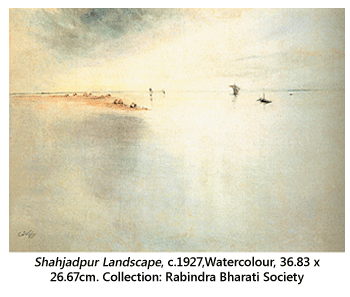

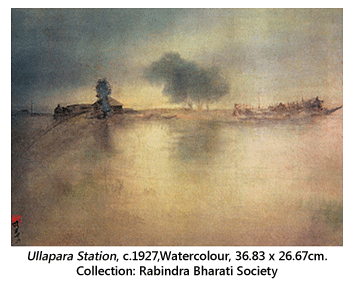

Around 1903 the Japanese wash technique, demonstrated by Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunso the two artists sent to Jorasanko by Okakura brought a radical change in Abanindranath's art. He enthusiastically responded to the dream-like quality of this painting method and noticed the way forms are made to remain dissolved in a veil of atmosphere. Consequently, Abanindranath produced some brilliant works poising his art almost silently somewhere in between the object-reality and a distant vision imbued with a poetic resonance. Paintings like Dewali (c.1903), Bharatmata (c.1905), Omar Khayyam series (c.1907-09), Sun Worshipper (c.1912-13) and Shahjadpur Landscape (c.1927) are some of the well known examples of his 'wash' paintings. Abanindranath's proclivity of transposing the ordinary into the domain of subtle evocative insinuations revealed the magical-romantic in him who wandered this visual world with a magic wand. '…both in his painting and his writing he had an alchemy of touch, investing his actual descriptions with the far-awayness of dreams and his fantasies with a strange palpability, an ambivalence one associates with a child's imagination. He himself recognized it; he reveled in telling stories to children, and to adults who had the child in them still alive.' 9

Paintings like Dewali (c.1903), Bharatmata (c.1905), Omar Khayyam series (c.1907-09), Sun Worshipper (c.1912-13) and Shahjadpur Landscape (c.1927) are some of the well known examples of his 'wash' paintings. Abanindranath's proclivity of transposing the ordinary into the domain of subtle evocative insinuations revealed the magical-romantic in him who wandered this visual world with a magic wand. '…both in his painting and his writing he had an alchemy of touch, investing his actual descriptions with the far-awayness of dreams and his fantasies with a strange palpability, an ambivalence one associates with a child's imagination. He himself recognized it; he reveled in telling stories to children, and to adults who had the child in them still alive.' 9

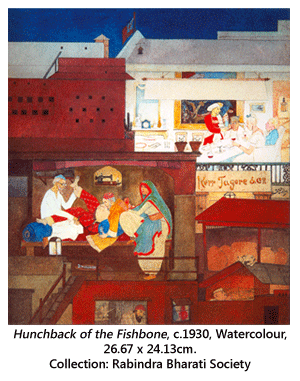

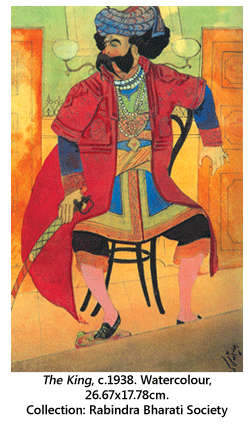

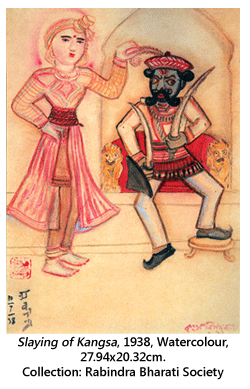

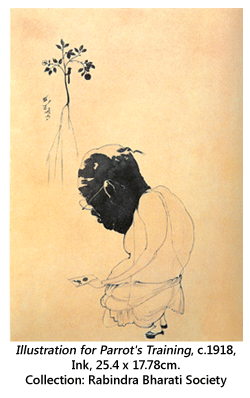

Whether it is the wonderful fictions for children, or moving reminiscences or serious academic deliberations like Bagishwari Shilpa Prabandhabali, Abanindranath is equally profound, intimate and playful. His language is evocative and carefully woven into a brocade of metaphors to the great delight of the readers, young and old. His descriptive idiom is often infused with the sensual flights, playful imaginative inflections and even subtle subversions. The master of story-telling himself, it is only natural for Abanindranath to cull his imageries from,  conceive his motifs and even paint entire series of works on literary sources like Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (c.1907-09), Kabikankan Chandi series (1938), Krishna Mangal series (c.1939) and others. Yet, his paintings, instead of functioning as secondary to the literary source, often supersede the narrative by reinterpreting it, and visually rendering it into another experience endowed with features intrinsic to visual language. From illustration they move on to allegory and later more personalized narration. 'Narration', R. Siva Kumar writes, 'was central to Abanindranath's art. The narrative impulse, as we have seen, informed both his landscapes and portraits, and they became involved and more engaging when they were inflected with narrative innuendoes.' 10 His playful insinuations begin to push the limits of these enterprises when in paintings like Arabian Nights (1930) he strategically upsets the hierarchy of history, culture, representation and conventions. Not only has he played on the Mughal miniature formats by including inscriptions in the Persian calligraphy style (albeit Bengali), he also allows characters and locations from his immediate colonial cosmopolitan neighborhood to participate in these resplendent visual dramas sourced from a distant cultural and geographical locale. By projecting his observations of local life into his images of Arabian Nights the 'artist-flaneur' in Abanindranath frees the colonized people from their frozen 'object-state' and empowers them with their own voice and own stories. In R. Siva Kumar's words, 'The social space that Abanindranath narrativized as an artist-flaneur is thus the subject of the Orientalist artist/writer read from the obverse.

conceive his motifs and even paint entire series of works on literary sources like Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (c.1907-09), Kabikankan Chandi series (1938), Krishna Mangal series (c.1939) and others. Yet, his paintings, instead of functioning as secondary to the literary source, often supersede the narrative by reinterpreting it, and visually rendering it into another experience endowed with features intrinsic to visual language. From illustration they move on to allegory and later more personalized narration. 'Narration', R. Siva Kumar writes, 'was central to Abanindranath's art. The narrative impulse, as we have seen, informed both his landscapes and portraits, and they became involved and more engaging when they were inflected with narrative innuendoes.' 10 His playful insinuations begin to push the limits of these enterprises when in paintings like Arabian Nights (1930) he strategically upsets the hierarchy of history, culture, representation and conventions. Not only has he played on the Mughal miniature formats by including inscriptions in the Persian calligraphy style (albeit Bengali), he also allows characters and locations from his immediate colonial cosmopolitan neighborhood to participate in these resplendent visual dramas sourced from a distant cultural and geographical locale. By projecting his observations of local life into his images of Arabian Nights the 'artist-flaneur' in Abanindranath frees the colonized people from their frozen 'object-state' and empowers them with their own voice and own stories. In R. Siva Kumar's words, 'The social space that Abanindranath narrativized as an artist-flaneur is thus the subject of the Orientalist artist/writer read from the obverse. He reclaims the colonial subjects' right to narrate their stories that was arrogated to themselves by the colonial rulers and perpetuated by presenting their readings as 'objective'. Abanindranath reasserts this right by recasting the Nights, a text central to the Orientalist representation of the East, by urging us to read his act of imagination contrapuntally with the text authenticated by the Orientalist.' 11

He reclaims the colonial subjects' right to narrate their stories that was arrogated to themselves by the colonial rulers and perpetuated by presenting their readings as 'objective'. Abanindranath reasserts this right by recasting the Nights, a text central to the Orientalist representation of the East, by urging us to read his act of imagination contrapuntally with the text authenticated by the Orientalist.' 11

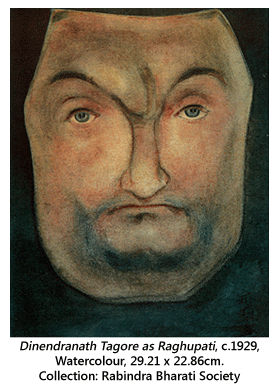

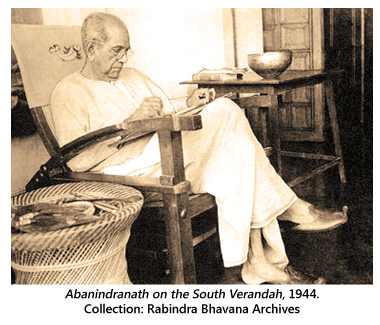

It seems that Abanindranath Tagore has been playing these subversive games over and over again in various garbs and with different intentions. His innumerable takes on traditional, folk and the popular turned upside down with remarkable freedom and eclectic assimilations are evident in plays written in Jatra format, Masks based on real characters and even in the katum-kutum (sculptural images fashioned from found objects, drift-woods, twigs and other scraps). In fact the last ten years of his life, till his death (5th December 1951), Abanindranath was passionately involved in producing these katum-movement and reposition him within the history of Indian modernisms of the early 20th century? There is a way in which Abanindranath, from the 1920s willfully writes himself out of history to play out his creative life within a private shell on stubbornly different terms.' 3 However, it is always instructive to see how the various coordinates the emotionally charged Swadeshi firmament, his momentous encounter with E. B. Havell (the great champion of the heritage of Indian art), exciting exposures to Japanese art through Okakura Kakuzo (a strong advocate of a pan-Asian aesthetic agenda), stimulating and scholarly participations of A. K. Coomaraswamy and Sister Nivedita in the revival movement and the hugely inspiring presence of the irresistible persona of his uncle Rabindranath Tagore shaped and influenced the formative stage of Abanindranath Tagore's artistic career.Born (7th August 1871) into the illustrious Tagore family of Jorasanko in north Calcutta, Abanindranath Tagore did not go through any formal art education but received all kinds of intellectual encouragement from the family charged with creative impulse and cultural awareness. As he grew up he realized that the prevailing art situation was critical, undecided and at times confused and unclear. On the one hand the perceived notion of modern art implied an attempt at recasting mythological subjects and genre scenes in Western realistic idiom and on the other hand the revivalist notion of modern Indian art got inseparably tied up with nationalistic aspiration as opposed to the colonial cultural hegemony. In between these two ends of the spectrum there were a number of professional artists catering to the patrons with limited tastes and over-specified uninspiring demands. Any artist envisaging a breakthrough from this rather frustrating situation would be looking at effecting some drastic changes in the art concepts and the overall cultural climate; not merely in the style and manner of art but in the basic rationale and vision of modern Indian art. When one locates Abanindranath Tagore in this context one can grasp the gravity of this mammoth uphill task faced up by any courageous artist of that time. His responsibilities thus happened to be manifold. As K. G. Subramanyan writes, 'He had to rescue art from the rigid conventionalisms of the traditional artist, he had to release it from the constrictions of pedestrian patronage, he had to reconcile it, at whatever point of contact, with its previous history. He had also to reckon with the new cultural fact that the cultivated Indian was coming out of his traditional predispositions and the old mythologies and symbols did not hold with him the same credence and immediacy as they did with his predecessors. So he had to begin afresh and seek a new language, starting with a personal bivouac with nature and environment.' 4

movement and the hugely inspiring presence of the irresistible persona of his uncle Rabindranath Tagore shaped and influenced the formative stage of Abanindranath Tagore's artistic career.Born (7th August 1871) into the illustrious Tagore family of Jorasanko in north Calcutta, Abanindranath Tagore did not go through any formal art education but received all kinds of intellectual encouragement from the family charged with creative impulse and cultural awareness. As he grew up he realized that the prevailing art situation was critical, undecided and at times confused and unclear. On the one hand the perceived notion of modern art implied an attempt at recasting mythological subjects and genre scenes in Western realistic idiom and on the other hand the revivalist notion of modern Indian art got inseparably tied up with nationalistic aspiration as opposed to the colonial cultural hegemony. In between these two ends of the spectrum there were a number of professional artists catering to the patrons with limited tastes and over-specified uninspiring demands. Any artist envisaging a breakthrough from this rather frustrating situation would be looking at effecting some drastic changes in the art concepts and the overall cultural climate; not merely in the style and manner of art but in the basic rationale and vision of modern Indian art. When one locates Abanindranath Tagore in this context one can grasp the gravity of this mammoth uphill task faced up by any courageous artist of that time. His responsibilities thus happened to be manifold. As K. G. Subramanyan writes, 'He had to rescue art from the rigid conventionalisms of the traditional artist, he had to release it from the constrictions of pedestrian patronage, he had to reconcile it, at whatever point of contact, with its previous history. He had also to reckon with the new cultural fact that the cultivated Indian was coming out of his traditional predispositions and the old mythologies and symbols did not hold with him the same credence and immediacy as they did with his predecessors. So he had to begin afresh and seek a new language, starting with a personal bivouac with nature and environment.' 4

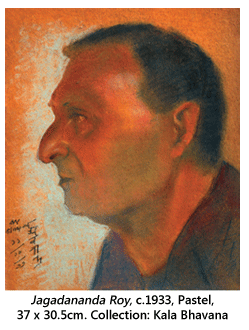

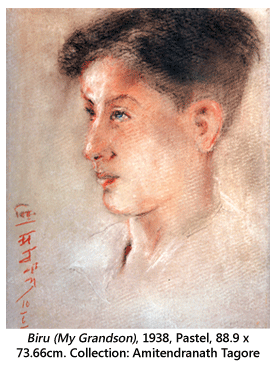

We know that in 1891-92 Abanindranath Tagore took lessons in the Western realistic art, as was the norm and preference in the elite-educated class of those days, first from the Italian artist O. Ghilardi (then, Vice Principal of the Calcutta School of Art) and later from an English artist C. L. Palmer. Though both these tutorials (mainly on still-life studies, portrait painting,  oil painting and pastel work) were short lived, the four pastel-portraits done in different times Rabindranath (c.1892), Debendranath (c.1893), another portrait of Rabindranath (c.1930) and the most poignant double portrait of artist's grandsons (done in late 1920s and reminiscent of early Italian Renaissance paintings) are stunning testimonials to the fact that Abanindranath had never forgotten these Western lessons and elevated them to an evocative plane in these and many other skillful works.

oil painting and pastel work) were short lived, the four pastel-portraits done in different times Rabindranath (c.1892), Debendranath (c.1893), another portrait of Rabindranath (c.1930) and the most poignant double portrait of artist's grandsons (done in late 1920s and reminiscent of early Italian Renaissance paintings) are stunning testimonials to the fact that Abanindranath had never forgotten these Western lessons and elevated them to an evocative plane in these and many other skillful works.

Yet, he was unhappy with the Victorian academic style of painting and he associated this brief period of formal training with failures and frustrations. The flipside of this restlessness is his notion of art as a romantic endeavor and art making as a personal space for contemplation. This “personal discontent” is, according to Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “… of central importance in nationalist perceptions in marking the break away from Western academic methods. In Abanindranath's career, this discontent coincided with his encounter with some new kinds of art that would dramatically change the course of his painting.” 5

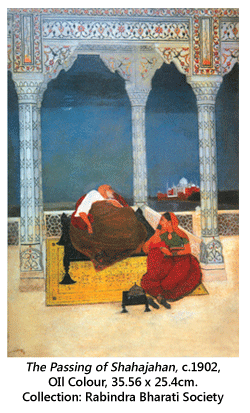

Arrival of and subsequent exposure to the illuminated manuscripts of Irish ballads and a folio of miniatures of Delhi qalam respectively certainly appear to be significant departure points for Abanindranath. Soon, he was looking at the possibilities of creating a fruitful contact with his artistic antecedents and the paintings of his Radha Krishna series (1893-95) are charming experiments on that. They are in a sense attempts at appropriating his own brand of “poetic naturalism”  with the compositional structures of Rajasthani or Pahari miniatures. In terms of these appropriations he achieved a greater degree of success when he came up with paintings like The Building of the Taj (1901) or The Death of Shah Jahan (c.1902) modeled after the framework of Mughal miniatures. Before we take a look at this more personal and individual journey let us have brief recapitulation of his encounter with Havell.

with the compositional structures of Rajasthani or Pahari miniatures. In terms of these appropriations he achieved a greater degree of success when he came up with paintings like The Building of the Taj (1901) or The Death of Shah Jahan (c.1902) modeled after the framework of Mughal miniatures. Before we take a look at this more personal and individual journey let us have brief recapitulation of his encounter with Havell.

E. B. Havell, who joined the Government School of Art in Calcutta in 1896 as its Superintendent, diverged away from the colonial project of teaching Western art and focused on the revival of Indian art in a big way. He brought down the specimens of European masterpieces from the Art School gallery and replaced them with Mughal and Rajput miniature paintings of India. Havell also believed that true art must permeate the daily life and activity of common people and thus set out to restore the rural arts and crafts of our country. This led to a remarkable change in the art school when he introduced a separate division called Industrial Art wherein artisans from various sectors were asked to join and work thus exposing the urban students to the rich tradition of Indian crafts, particularly the handloom works. When Abanindranath met Havell in 1897, the former was instantly inspired by the latter's vision. Though Abanindranath had never been his formal student, he regarded Havell as his guru and considered Havell's contribution to the Indian art scenario valuable and timely. Abanindranath took part in Havell's crusade for Indian art and supported its Nationalist cause. Later, in response to Havell's famous book “Ideals of Indian Art”, Abanindranath Tagore wrote to him in a letter written in 1911 'Many thanks for the valuable book, I shall keep it always as a valued present from my Guru whose unworthy chela I am. … How truly you have said “art does not die of over-praise, it can not live or thrive in an atmosphere of contempt and depreciation.”…It is time that Indians should feel the magnitude and grandeur of their art heritage and hope that your book will open their eyes.' 6

Later, in response to Havell's famous book “Ideals of Indian Art”, Abanindranath Tagore wrote to him in a letter written in 1911 'Many thanks for the valuable book, I shall keep it always as a valued present from my Guru whose unworthy chela I am. … How truly you have said “art does not die of over-praise, it can not live or thrive in an atmosphere of contempt and depreciation.”…It is time that Indians should feel the magnitude and grandeur of their art heritage and hope that your book will open their eyes.' 6

At the request of Havell, Abanindranath Tagore joined the Government School of Art as Vice-Principal in 1905. When in February 1906 Havell left India, Abanindranath had to take the additional responsibility of officiating as the Principal for three years until Percy Brown joined as the head. Abanindranath was to remain Vice-Principal until he resigned in 1915 but he continued to make himself available as a mentor in Jorasanko's Bichitra Sabha and later through the Indian Society of Oriental Art. Abanindranath during his tenure in the art-school was the head of the Advanced Design Class, a department which was later renamed 'Indian Painting' class. This was a crucial phase in his life as an art teacher formally heading a premier institution and taking some remarkable pedagogic decisions. For instance, in 1906 he appointed Iswari Prasad Verma a traditional painter belonging to the Patna Miniature Style as a teacher of foliage. After Abanindranath it was Iswari Prasad who became the head of the Indian painting section. As a guru Abanindranath inspired a whole battalion of accomplished students many of whom played noteworthy roles in spreading the ideals of Oriental art and establishing what later came to be known as the Bengal School Painting (though some writers prefer to call it the Neo-Indian School to suggest its influence and spread across the boundaries of Bengal). Nandalal Bose and Surendranath Ganguly were Abanindranath's very first students,  followed by Asit Kumar Haldar, Kshitindranath Majumdar, Sailendranath Dey, Surendranath Kar, Sarada Charan Ukil, K. Venkatappa and others. Many of his followers, barring a few like Nandalal Bose, failed to get to the depth of Abanindranath's teaching and ended up in imitating the Guru without much innovative approach and creative intervention.

followed by Asit Kumar Haldar, Kshitindranath Majumdar, Sailendranath Dey, Surendranath Kar, Sarada Charan Ukil, K. Venkatappa and others. Many of his followers, barring a few like Nandalal Bose, failed to get to the depth of Abanindranath's teaching and ended up in imitating the Guru without much innovative approach and creative intervention.

Despite his interests in traditional paintings and his attempts at restructuring the module of his art in terms of the mediaeval painting styles Abanindranath was also aware of the dangers of this kind of self-conscious style alignments. With regard to the tradition he often doubted its dated rules and norms. He was not at all comfortable with the shastric kutums or relatives-in-wood. With little or no crafting hundreds of these objects assumed identities, names and even stories. Discussing this curious involvement of Abanindranath, Debashish Banerji writes, 'The “artistry” here lay more in the eye than the hand, as the “finished” toys retained the ambiguity of natural or waste objects and came to life only with the sharing of their names.' 12

In the Introduction to his huge book on Abanindranath Tagore's paintings, R. Sivakumar remarks that Abanindranath is an artist 'who is more talked about than seen. In this he is like a classic that is little read but is a part of our cultural consciousness.' 13 This book of course compensates that lacuna to a great extent. Abanindranath's art is now readily available to see, albeit reproductions. But a retrospective show is still due and generations of viewers are yet to experience the originality, depth, complexities and effortlessness of the works of this outstanding artist of all times. 'Abanindranath's life as an artist is comparable with the followers of sahajia cult. This is because his art and art-ideas have found their expression almost effortlessly. No part of his artistic life is weighed down by factual burden. This candid unfolding of his journey is rare in modern times.' Benode Behari Mukherjee sums up quite succinctly. 14

Notes:

1. Abanindranath Tagore, Shilpayan ( Kolkata: Anando Publishers, 1989) p47

2. Ella Dutta, “Abanindranath Tagore a new context”, Contemporary Indian Art: Other Realities, ed. Yashodhara Dalmia (Mumbai: Marg, vol.53 no.3, 2002, reprinted 2008) p.20

3. Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “Abanindranath, Known and Unknown: The Artist versus the Art of his Times”, Art & Visual Culture in India 1857 2007, ed. Gayatri Sinha (Mumbai: Marg, 2009) p.84

4. K. G. Subramanyan, “The Phenomenon of Abanindranath Tagore”, Abanindranath (Santiniketan: Abanindra Centenary Celebration Committee 1973) pp 34-35

5. Tapati Guha-Thakurta, The Making of a New “Indian” Art: Artists, aesthetics and nationalism in Bengal, c.18501920 (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press,1992) p.233

6. Uma Das Gupta, “Letters: Abanindranath to Havell” The Visva Bharati Quarterly Ed. Kalidas Bhattacharrya, vol.46 No.1,2,3 & 4: May 1980 April 1981 (Santiniketan: Visva Bharati 1982) pp.216-217

7. Nandan, Ed.Dinkar Kowshik (Santiniketan: Department of History of Art, Kala Bhavana1986) p.28

8. Ibid., p.28

9. K. G. Subramanyan, op.cit., p. 37

10. R. Sivakumar, Paintings of Abanindranath Tagore (Kolkata: Pratikshan, 2008) pp.255-256

11. Ibid., P.316

12. Debashish Banerji, The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore (New Delhi: Sage Publications,2010) p.118

13. SIvakumar, op.cit., p.19

14. Benode Behari Mukherjee, “Abanindra-Chitra”, Chitrakatha, ed. Kanchan Chakraborty (Kolkata: Aruna Prakashani 1984) p.284