- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

Museum

by Anurima Sen

Marble Palace, named by Lord Minto, is a whimsically built nineteenth century mansion in North Kolkata. Located at 46, Muktaram Babu Street, Chorbagan, it is one of those quirky palatial houses that represent the spirit of grandeur and extravagance of 19th Century Calcutta. In order to visit the house one must obtain a permit twenty four hours in advance from the West Bengal Tourism Information Bureau at BBD Bag, Kolkata. Entry is free, and there are guides-who occasionally demand baksheesh- to give visitors a tour of the house on all days (except Mondays and Thursdays) from 10am in the morning to 4pm in the evening.

As the name sufficiently suggests, the mansion is widely known because of its marble wall-panels and floors- made exclusively from one hundred and twenty six types of colourful Italian marble that had been transported across the seas. Built in 1835 by Raja Rajendra Mullick, it continues to be a residence for his descendants. He was an affluent businessman and the adopted son of Nilmoni Mullick. There exists an old Jagannath temple built by Nilmoni Mullick within the premises, which predates the house itself.

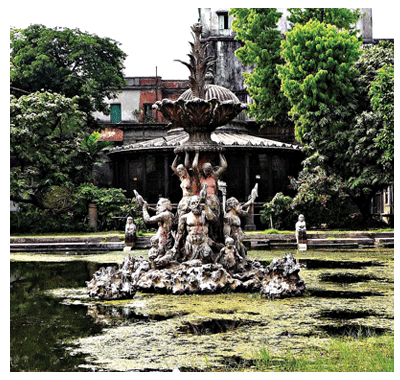

The white façade of the house imparts an impression of rapidly declining opulence. The structure is stately, but now in a state of disrepair. The enormous grounds contain innumerable statues, a pond with a beautifully crafted stone-fountain (now possibly defunct) featuring mermen and mermaids, the Marble Palace zoo and a miniature rock garden. The statues provide a taste of what to expect within the house itself: sheer eccentricity.  Scattered all over the grounds are figures of lions, some keeping vigil and some fast asleep, and accompanying them are sculptures of Gautam Budhha, gods from the Hindu pantheon, Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ and even Christopher Columbus! There is also an unassumingly small statue of Raja Rajendra Mullick himself, placed near the entrance. There are seating arrangements all across the lawn, sometimes accompanied by tables with impressive marble table-tops. As for the aviary, it still plays hosts to birds of exotic origin- from toucans and hornbills to pelicans. Apart from birds, there are several species of deer being kept here within small enclosures, such as the spotted deer and the barking deer. A little known trivia is that this was the first zoo opened in India.

Scattered all over the grounds are figures of lions, some keeping vigil and some fast asleep, and accompanying them are sculptures of Gautam Budhha, gods from the Hindu pantheon, Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ and even Christopher Columbus! There is also an unassumingly small statue of Raja Rajendra Mullick himself, placed near the entrance. There are seating arrangements all across the lawn, sometimes accompanied by tables with impressive marble table-tops. As for the aviary, it still plays hosts to birds of exotic origin- from toucans and hornbills to pelicans. Apart from birds, there are several species of deer being kept here within small enclosures, such as the spotted deer and the barking deer. A little known trivia is that this was the first zoo opened in India.

The broad stairs that lead into the mansion are now seldom used, and visitors are only allowed to enter the house through a side entrance leading straight into the Billiard Room. It almost feels like stepping back in time, and landing straight into an antique shop! One only wishes it was well-lit enough to make sense of even half the objects that have been amassed over the years in these huge, airy rooms. There are two billiard tables, of different sizes, placed in the centre of this room, and along the sides there are statues and vases that have been collected from all over the world. There are sculptures of Apollo, Faun and Flora amongst others- but what captures one's attention is the incredible Japanese bronze vase placed near one of the doorways. The next room is, incredibly enough, just about dedicated to Queen Victoria.  Occupying centre space is a larger-than-life wooden statue of the Queen, carved out from a single tree trunk. There is another remarkable bronze bust of the Queen in the same room, along with one of Medusa. A huge chandelier hangs in this comparatively smaller space, and a gramophone record player is kept covered in a corner of the room. The wooden ceiling is as intricately designed as the colourful marble floor. This room leads into the “jalsha-ghar”, or the music room. It is here that one gets a taste of the Raja's penchant for elaborate candle stands- either carved out of marble, or made from Belgian glass. Even the walls of the room have been decked in marble. The floors bear multicolored marble inlay on a giant scale, with a calico effect. The guide informs us that the modest piano which stands near the windows is the first piano imported to India, though this fact remains unverified. It appears that the instrument is still in near-perfect condition. Statues of Napoleon Bonaparte have been kept here, along with others from Greek and Roman mythology. Thus, we have Autumn and Spring, Agriculture and Commerce, Summer and Winter, and finally, Dawn and Night personified in the forms of beautiful men and women, facing each other, kept on opposite sides of the room. There are two paintings hung at the back of the room: that of Venus de Medici and Venus with Cupid. From here, one steps into the courtyard from where one can take a look at the overall structure of the house. The design is a curious medley of traditional Bengali, Oriental and Neoclassical styles of architecture. The sprawling open courtyard, accompanied by the place of worship (or “thakur-dalan”, as it termed in Bengali) are markedly Indian influences for example, whereas the tall Corinthian pillars, the sloping roofs are reminiscent of a Chinese pavilion. This alone exemplifies the absolutely unconventional and strange nature of this lavishly built mansion.

Occupying centre space is a larger-than-life wooden statue of the Queen, carved out from a single tree trunk. There is another remarkable bronze bust of the Queen in the same room, along with one of Medusa. A huge chandelier hangs in this comparatively smaller space, and a gramophone record player is kept covered in a corner of the room. The wooden ceiling is as intricately designed as the colourful marble floor. This room leads into the “jalsha-ghar”, or the music room. It is here that one gets a taste of the Raja's penchant for elaborate candle stands- either carved out of marble, or made from Belgian glass. Even the walls of the room have been decked in marble. The floors bear multicolored marble inlay on a giant scale, with a calico effect. The guide informs us that the modest piano which stands near the windows is the first piano imported to India, though this fact remains unverified. It appears that the instrument is still in near-perfect condition. Statues of Napoleon Bonaparte have been kept here, along with others from Greek and Roman mythology. Thus, we have Autumn and Spring, Agriculture and Commerce, Summer and Winter, and finally, Dawn and Night personified in the forms of beautiful men and women, facing each other, kept on opposite sides of the room. There are two paintings hung at the back of the room: that of Venus de Medici and Venus with Cupid. From here, one steps into the courtyard from where one can take a look at the overall structure of the house. The design is a curious medley of traditional Bengali, Oriental and Neoclassical styles of architecture. The sprawling open courtyard, accompanied by the place of worship (or “thakur-dalan”, as it termed in Bengali) are markedly Indian influences for example, whereas the tall Corinthian pillars, the sloping roofs are reminiscent of a Chinese pavilion. This alone exemplifies the absolutely unconventional and strange nature of this lavishly built mansion.

A wooden staircase leads to the first floor of the house, part of which remains inaccessible as people still live in those quarters.  Though this area is dimly lit, several paintings hang from the walls, such as Marine View by Van Goyan, Guercino's Venus and Adonis, Sassoferato's Madonna and Child, and some others by Ravi Varma. The frames are also noteworthy; most of them are ornate and gold-polished. The rooms on the first floor have a distinctly Baroque flavour, dramatically enshrined with full-length mirrors. Here, one can take a look at the remarkable collection of antique furniture, Western sculpture and of course, a fine collection of paintings. The first room to the left is the Meeting Room, housing art works, silver show-pieces, huge chandeliers, and Belgian glass mirrors. The next room is the “nach-mahal”, once entirely carpeted with seating arrangements on both sides of the room. Apart from the chandeliers, the other objects that merit attention here are the antique clocks. The corridor itself is crammed with vases, paintings, marble and wooden sculptures as well as exotic birds, such as the Red Rosella and Eastern Rosella from Australia, and the Sun Conour from South America. Vibrant, like the rooms themselves, the birds seem to embody the quintessence of the Marble Palace. One can detect a bust of George Washington, of Satyrs and a series of paintings depicting scenes from the Old Testament in these corridors. A huge brass hookah is kept near a doorway, with remarkably intricate designs carved upon it.

Though this area is dimly lit, several paintings hang from the walls, such as Marine View by Van Goyan, Guercino's Venus and Adonis, Sassoferato's Madonna and Child, and some others by Ravi Varma. The frames are also noteworthy; most of them are ornate and gold-polished. The rooms on the first floor have a distinctly Baroque flavour, dramatically enshrined with full-length mirrors. Here, one can take a look at the remarkable collection of antique furniture, Western sculpture and of course, a fine collection of paintings. The first room to the left is the Meeting Room, housing art works, silver show-pieces, huge chandeliers, and Belgian glass mirrors. The next room is the “nach-mahal”, once entirely carpeted with seating arrangements on both sides of the room. Apart from the chandeliers, the other objects that merit attention here are the antique clocks. The corridor itself is crammed with vases, paintings, marble and wooden sculptures as well as exotic birds, such as the Red Rosella and Eastern Rosella from Australia, and the Sun Conour from South America. Vibrant, like the rooms themselves, the birds seem to embody the quintessence of the Marble Palace. One can detect a bust of George Washington, of Satyrs and a series of paintings depicting scenes from the Old Testament in these corridors. A huge brass hookah is kept near a doorway, with remarkably intricate designs carved upon it.

The next stop in the tour is the Painting Room. Although the entire house bears testimony to the grand collection that the Raja had, this room houses the best of them all. These include Rubens' The Marriage of St. Catherine and Amazon's War, Murillo's The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, Sir Joshua Reynold's The Infant Hercules Strangling the Serpent, and Venus and Cupid, and John Opie's Shower of Gold amongst others. An impressive (and still functional) grandfather clock stands in one corner of the room, though it is understandably dwarfed by the vast canvases.

Geoffrey Moorhouse, in his book, “Calcutta: The City Revealed,”  says it looks “as if [the objects on display] had been scavenged from job lots on the Portobello Road on a series of damp Saturday afternoons.” Such a brusque statement, I believe, is quite off-the-mark. Just as it would be folly to assume that all the artifacts scattered around the house are equally valuable or aesthetically appealing, it would also be grossly unjust to devalue this immense assortment of things on the basis of disharmony. It has to be kept in mind that most of these objects of art had been presented to Raja Rajendra Mullick as gifts- this is the main reason behind the collection's clashing styles. One needs to overcome the first jolt of perceiving elements from Greek, Roman and Indian mythology freely mixing with Biblical figures and sculptures of little orphaned girls and fisherwomen, in order to appreciate the intense creativity behind them. The apparent disharmony of the artifacts in this palatial edifice must be disregarded in order to realize the cultural wealth that has been amassed here over the ages- the palace has art and historical relics of over ninety countries across the world, a diverse medley of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, as well as an exquisite collection of around eighty antique clocks. Yet, the Marble Palace sadly remains undervalued as a tourist attraction despite being a treat for both art connoisseurs and collectors. Perhaps with a little care and renovation, this strange, old house could be transformed into a museum housing an enviable collection.

says it looks “as if [the objects on display] had been scavenged from job lots on the Portobello Road on a series of damp Saturday afternoons.” Such a brusque statement, I believe, is quite off-the-mark. Just as it would be folly to assume that all the artifacts scattered around the house are equally valuable or aesthetically appealing, it would also be grossly unjust to devalue this immense assortment of things on the basis of disharmony. It has to be kept in mind that most of these objects of art had been presented to Raja Rajendra Mullick as gifts- this is the main reason behind the collection's clashing styles. One needs to overcome the first jolt of perceiving elements from Greek, Roman and Indian mythology freely mixing with Biblical figures and sculptures of little orphaned girls and fisherwomen, in order to appreciate the intense creativity behind them. The apparent disharmony of the artifacts in this palatial edifice must be disregarded in order to realize the cultural wealth that has been amassed here over the ages- the palace has art and historical relics of over ninety countries across the world, a diverse medley of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, as well as an exquisite collection of around eighty antique clocks. Yet, the Marble Palace sadly remains undervalued as a tourist attraction despite being a treat for both art connoisseurs and collectors. Perhaps with a little care and renovation, this strange, old house could be transformed into a museum housing an enviable collection.