- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

Profile

Tapas Konar was born (in 1953), in Parul, the village in Hooghly district with some beautiful terracotta temples. He grew up to early youth in that rural part of West Bengal. He emigrated to Kolkata for earning a livelihood, in 1974. Nostalgic relationships make him still visit the native place regularly. Although, as we shall see that, he has great deal to do with nature in his work, yet, no descriptive details of his native place, neither the sky, land,  water divisions nor the flora and fauna of the area, ever enter Tapas' art as identity markers of location. Tapas avoid all reference to visible phenomenon (other than human figures) for descriptive purposes. Emigrating from rural Hooghly, in search of a livelihood, he drifted to the Indian College of Art and Draughtsman ship of Kolkata (at a period when the institution was passing through a particularly bad patch of time). This school inherited a legacy of adherence to illusionistic representation of visible phenomena only, through anatomical drawing, optical perspective, foreshortened images and chiaroscuroistic methods of light-and-shade variations for 3-dimensional effects. From a basic dislike of the manner in which education was imparted, Tapas refused to adhere to any of the norms. Tapas would rather follow up the pre-art school lessons he took from Hariprasad Medda who claimed to have been a pupil of Acharya Nandalal Bose. Indicating draped human figures by lyrically flowing contour lines, without filling them up with physical details, is one lesson that Tapas seems to have learnt early. The mature Tapas Konar further detaches the draped human figure from anatomy, by indicating those by quivering contour lines, to give out the feeling of agitation within. Tapas would like to think that his mode of rendering human body sans its physicality is a means of foregrounding its emotive capacity, and it comes from his love of Abanindranath, Nandalal and their followers. Question, however is which works of these two masters he is particularly referring to. One is surer about Tapas' debt to Abanindranath in his choice and use of tonally graded colours and muted tones to indicate diurnal-nocturnal cycle and atmospherics for mood generation.

water divisions nor the flora and fauna of the area, ever enter Tapas' art as identity markers of location. Tapas avoid all reference to visible phenomenon (other than human figures) for descriptive purposes. Emigrating from rural Hooghly, in search of a livelihood, he drifted to the Indian College of Art and Draughtsman ship of Kolkata (at a period when the institution was passing through a particularly bad patch of time). This school inherited a legacy of adherence to illusionistic representation of visible phenomena only, through anatomical drawing, optical perspective, foreshortened images and chiaroscuroistic methods of light-and-shade variations for 3-dimensional effects. From a basic dislike of the manner in which education was imparted, Tapas refused to adhere to any of the norms. Tapas would rather follow up the pre-art school lessons he took from Hariprasad Medda who claimed to have been a pupil of Acharya Nandalal Bose. Indicating draped human figures by lyrically flowing contour lines, without filling them up with physical details, is one lesson that Tapas seems to have learnt early. The mature Tapas Konar further detaches the draped human figure from anatomy, by indicating those by quivering contour lines, to give out the feeling of agitation within. Tapas would like to think that his mode of rendering human body sans its physicality is a means of foregrounding its emotive capacity, and it comes from his love of Abanindranath, Nandalal and their followers. Question, however is which works of these two masters he is particularly referring to. One is surer about Tapas' debt to Abanindranath in his choice and use of tonally graded colours and muted tones to indicate diurnal-nocturnal cycle and atmospherics for mood generation.

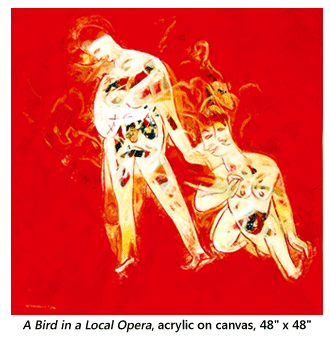

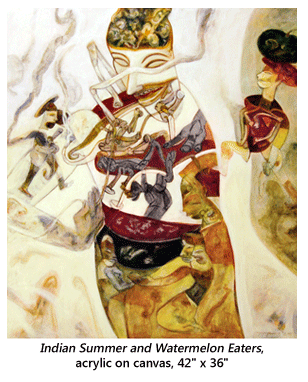

Tapas have no use, in his work, for background and foreground for staging his human dramas. It is usually one whole pictorial plane for him. Tapas' use of pictorial space as a uniplanimetric two-dimensional surface is to a large extent, the resultant effect of his non-chiaroscuroistic use of colour tonalities. While in his small watercolours and sketches single and/or two-figure images are posited on blank unadorned surfaces, to focus attention on the construction and the emotive effect of the imagery, in more elaborate paintings,  the backgrounds are non-descriptive playgrounds of colour-tones, functioning as eloquent settings for enactment of charged drama.

the backgrounds are non-descriptive playgrounds of colour-tones, functioning as eloquent settings for enactment of charged drama.

The first elements of the settings, Tapas designs for his non-performing dramas are the indications of time within the diurnal-nocturnal cycle, as also of time within the cycle of seasons. Both the cycles are indicated by choice of particular use of hues of colour for getting proper intensities of illumination (or its lack), to create the perception of time ranging from twilight, to dusk, to lit night, to dawn. The next, that is the indications of season related atmospherics come with tonal gradations of colours, their spread over pictorial surface. The application of colours also needs to be noticed. Tapas have almost no use for saturated colours and he mutes their brilliance commensurate with tonal gradations. Due to the kind of application of colours and handling of tonalities, the indicated twilight appears as seen through a veil of summer dust, the dusk as seen through a film of suspended water particles of monsoon, or a night scene as lit up by stars in autumn sky, or light of dawn as if filtering in through a translucent curtain of winter mist. All of Tapas' endeavors in respect of colour and tonalities are governed by the intention of affecting such feelings.

The other most striking aspect of the settings, Tapas designs for his non-performing plays, are the pictorial space to colour-tone and the colour-tone to pictorial space relationships, seen in his more elaborate paintings. In conventional 'realistic' (erroneously called) work tonal gradations are instruments of creation of illusion of volumes of objects in the path of light's travel from a single source, and of illusion of receding details in field of observation with increase of distance from the observer. Tapas have no use for this kind of chiaroscuroistic function of tonal gradation of colour. Tapas' choice and use of colour and tonalities are governed by the intention of generation of mood through evocation of association with particular periods of diurnal-nocturnal cycle and weather. He seems to have derived this evocative use of colour-tones from the early wash paintings of Abanindranath. From a social-psychological point of view, such an association of mood with cycle of time and weather is pre-industrial pre-urban. Yet, Tapas sometimes divides his pictorial space into different tonal zones with indications of straight-linear shafts of light, as if coming from a definite source. But as the larger areas of these paintings do not exhibit any evidence of adherence to the rules of chiaroscuro, this devise too gets revealed as one means of creation of ambiguity of meaning. However, the particular method of dividing the uniplanimetric surface into segmented areas of disparate episodes is a development from Gaganendranath through K.G. Subramanyan. The third most striking aspect, of Tapas' more elaborate paintings, is the difference he makes between the painted surface, and the human beings in action that he supposedly represents. As Tapas' paintings are all on human action and motivation for action, this aspect becomes very important. We have already seen that the human images in action postures are indicated by non-anatomical quivering lines and are without details of physical features. Non-chiaroscuroistic attempt in endowing of physical volume to these is discernible. More importantly, the ambient colour-tones of the negative pictorial space (i.e. the space un-occupied by image) often freely enter the bodies penetrating through contour-outlines. These applications make the images, ones in union with surrounding natural atmosphere. In the process of such penetration of atmospheric light, the images get divested of physical substance.

As Tapas' paintings are all on human action and motivation for action, this aspect becomes very important. We have already seen that the human images in action postures are indicated by non-anatomical quivering lines and are without details of physical features. Non-chiaroscuroistic attempt in endowing of physical volume to these is discernible. More importantly, the ambient colour-tones of the negative pictorial space (i.e. the space un-occupied by image) often freely enter the bodies penetrating through contour-outlines. These applications make the images, ones in union with surrounding natural atmosphere. In the process of such penetration of atmospheric light, the images get divested of physical substance.

Tapas' long struggle with several arts finally bore fruit, when he got recognition by being awarded the Lalit Kala National Award in 2002. Tapas is fifty five now. Some years back, he gave up his job to devote all his time to creative thinking and realization of thought in visual form. Among his contemporaries he is alone in the kingdom of his thought. He seems to be driven to his creativity by a will to discourse on a mystic energy at the root of what is identified as genuinely spiritual, that is, not sanctioned by any religious authority or propagated by an institution. But as he does not depend upon mythological or allegorical narrative, it becomes quite problematic for him to construct the visual correlatives. Fortunately, his works do approximate the deep idea content. One only wishes, that Tapas goes a little more for expression of spiritual of mystic experience and puts a lesser stress on discourse. He has long working years ahead of him and promise; he can pursue the ideal of perfectly matching his constructional innovations with abstruse contemplation. But he has to travel the path he has chosen alone.