- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

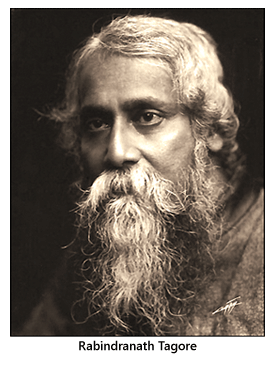

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Rabindranath as Painter

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

by R. Siva Kumar

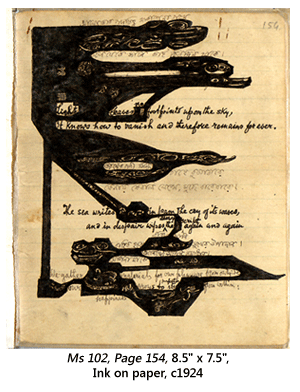

Rabindranath had always wanted to paint but he eventually found himself as a painter only when he was 63. After doodling in his manuscripts and turning his textual deletions into decorative motifs for over two decades almost all of a sudden in 1924 on the pages of the Purabi Manuscript it began to proliferate and assume more representational and expressive intent. Victoria Ocampo who spotted these during his stay in Argentina as her guest was impressed and found artistic merit in them. This in turn made him aware of their artistic potential. Compared to his early doodles it is clear that these were not entirely spontaneous but inspired by the examples of Primitive art he had been looking at. In these the decorative is conjoined with the grotesque and the fantastic as in many traditions of non-Western art gathered under the rubric of 'Primitive art'.

Rabindranath had always wanted to paint but he eventually found himself as a painter only when he was 63. After doodling in his manuscripts and turning his textual deletions into decorative motifs for over two decades almost all of a sudden in 1924 on the pages of the Purabi Manuscript it began to proliferate and assume more representational and expressive intent. Victoria Ocampo who spotted these during his stay in Argentina as her guest was impressed and found artistic merit in them. This in turn made him aware of their artistic potential. Compared to his early doodles it is clear that these were not entirely spontaneous but inspired by the examples of Primitive art he had been looking at. In these the decorative is conjoined with the grotesque and the fantastic as in many traditions of non-Western art gathered under the rubric of 'Primitive art'.

These doodles of 1924 mark the beginnings of Rabindranath's artistic career and Rabindranath himself recognised them as such and wrote: 'The only training I had from my young days was the training in rhythm in thought, the rhythm in sound. I had come to know that rhythm gives reality to that which is desultory, which is insignificant in itself. And therefore, when the scratches in my manuscript cried, like sinners, for salvation, and assailed my eyes with the ugliness of their irrelevance, I often took more time in rescuing them into a merciful finality of rhythm than in carrying on what was my obvious task.' He also called this his 'unconscious training in drawing.'

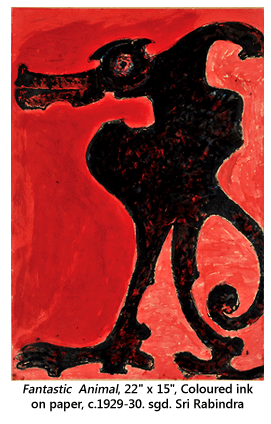

Switching from writing to giving finality to his doodles he sometimes erased an entire page of writing and turned it into a page of drawing. This freed the image from the text and made it independent but he did not take to doing independent paintings until 1928. His initial paintings of imaginary animals and birds and mask like faces were akin to the doodles. They exist half way between the real and the possible, the primeval and the surreal. While some of his imaginary creatures have an organic unity that suggests an anatomical probability, others have forms composed from decorative motifs as in Chinese ritual bronze vessels or ancient Peruvian carvings,  and yet others have forms that break up into geometric units or bodies and are pure inventions with animation borrowed from of real animals. He achieves this largely though the creation of composite forms and cross-projections of movement or expression. Although gradually perceived reality begins to influence the formation of images the spirit of cross-projection, of knowing things by inhabiting them, continued to inform his work.

and yet others have forms that break up into geometric units or bodies and are pure inventions with animation borrowed from of real animals. He achieves this largely though the creation of composite forms and cross-projections of movement or expression. Although gradually perceived reality begins to influence the formation of images the spirit of cross-projection, of knowing things by inhabiting them, continued to inform his work.

Imagination and serendipity played a greater role than planned execution in the early works and his innate sense of rhythm that structured the forms introduced an element of abstraction into his paintings. Commenting on it, he wrote: 'It is the element of unpredictability in art which seems to fascinate me strongly. The subject matter of a poem can be traced back to some dim thought in the mind… While painting, the process adopted by me is quite the reverse. First there is the hint of a line, and then the line becomes a form. The more pronounced the form becomes the clearer becomes the picture to my conception. This creation of form is a source of wonder. If I were a finished artist I would probably have a preconceived idea to be made into a picture.  This is no doubt a rewarding experience. But it is greater fun when the mind is seized upon by something outside of it, some surprise element which gradually evolves into an understandable shape.'

This is no doubt a rewarding experience. But it is greater fun when the mind is seized upon by something outside of it, some surprise element which gradually evolves into an understandable shape.'

But painting also opened him to the world of visual sensations and made him see the world anew. He wrote, 'when I turned to painting, I at once found my place in the grand cavalcade of the visual world. Trees and plants, men, beasts, everything became vividly real in their own distinct forms. The lines and colours began revealing to me the spirit of the concrete objects in nature. There was no more need for further elucidation of their raison d'être once the artist discovered his role of a be holder pure and simple.' He also wanted the viewers to approach his paintings as they approached nature and know them through empathy and sensibility. And so he refused to name his paintings, and to come between them and their viewers.

In his paintings meanings did not exist separate from form; to him the painted image was more like nature than language and this gave it greater claim to permanence and a communicativeness that transcended cultures. Comparing the relative permanence of the arts he wrote: 'All kinds of poetic works die with language… But there is no such hassle with nature. The Krishnachura gave us Krishnachura flowers yesterday, so it does today and so it will tomorrow. Every difficulty is with language. In a way paintings are much more enduring. The difference between what is grasped by the eyes and what is grasped by language lies in this.'

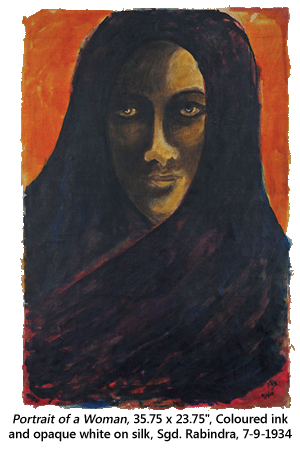

Painting awakened him to the evocative power of forms in nature and in his painting too he wanted to express through the sensory aspects forms. In this he was in tune with the approach adopted by modern artists who believed in the aesthetic autonomy of mediums.  The most recurring form in his paintings was the human face; his interest in it remained constant but his approach to its rendering did not remain fixed. The earliest ones are more mask-like. Some of these remind us of Peruvian or Indonesian masks, but more often they reflect an effort to turn a seen face into a social or universal type. Without any reference to the body, of which the face is a part, they usually float on the page, and like actual masks they represent the face as a form complete in itself.

The most recurring form in his paintings was the human face; his interest in it remained constant but his approach to its rendering did not remain fixed. The earliest ones are more mask-like. Some of these remind us of Peruvian or Indonesian masks, but more often they reflect an effort to turn a seen face into a social or universal type. Without any reference to the body, of which the face is a part, they usually float on the page, and like actual masks they represent the face as a form complete in itself.

Yet within a short period his faces begin to function as a formal synecdoche for the whole body. Etched into their lineaments are the signs of the absent body and we can see them with our mind's eye if we pay attention to the painterly, materiality of these painted faces. As his repertoire of skills grew the faces became more individualised as in portraits. Shadows of people he had seen and known began to fall across his painted faces. But for Rabindranath who believed that the self was always evolving and who was ever unravelling his self, portraits did not mean likeness but something deeper and truer than likeness, more akin to what writers call character. And, amalgamating the social and individual, it is in this direction that his representations of the human face finally moves.

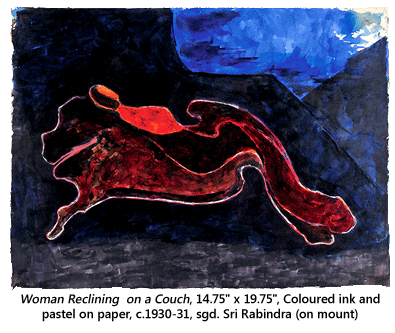

Discovering the human body was for Rabindranath a part of discovering nature afresh through painting.  Considering that he was to the world the white-beard, long-robbed, serious-minded poet his figures are surprisingly agile, light and sometimes acrobatically animated. That his involvement with dance took a definitive turn about the same time as he was beginning to painting perhaps explains this. In 1927 while visiting Java he was greatly impressed by their dances and felt that their life expressed itself through dance; he wrote: 'Here, when their life seeks utterance, it sets them a-dance… I have seen their plays; it is movement from the beginning to end… In this dance the tongue is silent, but they speak with their whole body through signs and gestures.' In his paintings too the tongue is silent and the figure speaks through movement and gesture.

Considering that he was to the world the white-beard, long-robbed, serious-minded poet his figures are surprisingly agile, light and sometimes acrobatically animated. That his involvement with dance took a definitive turn about the same time as he was beginning to painting perhaps explains this. In 1927 while visiting Java he was greatly impressed by their dances and felt that their life expressed itself through dance; he wrote: 'Here, when their life seeks utterance, it sets them a-dance… I have seen their plays; it is movement from the beginning to end… In this dance the tongue is silent, but they speak with their whole body through signs and gestures.' In his paintings too the tongue is silent and the figure speaks through movement and gesture.

Committed to expressing himself through visual and sensuous means such as movement and gesture, Rabindranath kept narration out of his paintings and instead imbued his figures with a character or bhab (mood) that could be expressed formally. He gave expression to it in two different ways. He sometimes condensed the sensations or the bhab aroused by a figure into a motif, or a single iconic image. In such images the figure assumes a denser, non-anatomical decorative shape; undergoes an expressive metamorphosis comparable to the transformation of a hand into a fist. The process remains the same even when there is more than one figure;  the figures are then fused in to a single motif and seen as constituting an individual biomorphic shape. And when a figure is seen in relation to an object, they are similarly amalgamated into a single entity with the object assuming human overtones.

the figures are then fused in to a single motif and seen as constituting an individual biomorphic shape. And when a figure is seen in relation to an object, they are similarly amalgamated into a single entity with the object assuming human overtones.

He also sometimes transforms a group of figures into an engaging moment. In paintings conceived as a moment he does not condense or fuse figures, but retain their discreteness and individuality; it revolves around turning the picture into a gestalt of gestures. Like other modernist painters while trying to free painting from literature he recognised that two or more figures brought together paved the way for painting's own kind of narration. But unlike in literature where a story is unravelled through characters developed through successive events, in painting a gestalt of gesturing figures leads us towards a theatrical moment. In these paintings where he explores the narrative and expressive potential of the body in movement and gesture Rabindranath uses insights gained from theatre just as he brought a writer's sense of character into his rendering of faces. Dramatically pregnant as these moments are, their meanings are tantalisingly ambivalent; they lend themselves to partial unravelling when they are read experientially from within, but becomes intractable as soon as we try to read them according to some external code.

Like these dramatic scenes his landscapes too are soundless. Devoid of human figures and with very few suggestions of human presence in them, to him landscape represents a one to one intimate encounter with the world. There are echoes of an old habit that bordered on the spiritual in these pictures. In The Religion of Man Rabindranath wrote: 'Almost every morning in the early hour of dusk, I would run out from by bed in a great hurry to greet the first pink flush of the world… The sky seemed to bring to me the call of a personal companionship, and all my heart my whole body in fact used to drink in at a draught the overflowing light and peace of those silent hours.'  Only in these pictures painted in his mature years the scene and the twilight silence is not that of dawn but of dusk. With trees ominously silhouetted against iridescent skies or dense woodlands patiently mapped in dim evening light, those familiar with old Santiniketan will recognise experiential elements in these landscapes, but they are more archetypal than descriptive and with enchanting pools of light and shadow they draw us in rather than unfold.

Only in these pictures painted in his mature years the scene and the twilight silence is not that of dawn but of dusk. With trees ominously silhouetted against iridescent skies or dense woodlands patiently mapped in dim evening light, those familiar with old Santiniketan will recognise experiential elements in these landscapes, but they are more archetypal than descriptive and with enchanting pools of light and shadow they draw us in rather than unfold.

Art was for Rabindranath self-expression, or more precisely an expression of the artist's personality. Though as a painter he was no virtuoso and possessed limited representational skills, his graphic skills and rhythmic sense were commendable. He was by his own admission an artist who found rather than one who created according to a pre-defined idea but once the image surfaced the richness of thinking and imagination gained from creative work in other fields took over and guided it to its expressive finality. Perhaps there is a late Tagore both in his paintings and poems who was more personal in expression. And if there is darkness in his paintings there is also playfulness in them and unlike the Expressionists with whom he is often compared he did not cease to feel a deep empathy with nature even in his darkest moments.