- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

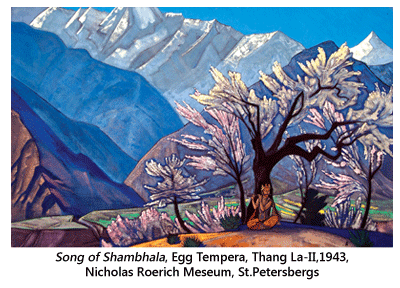

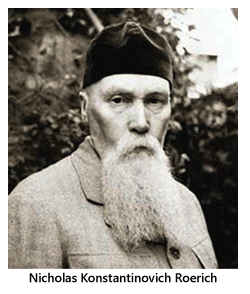

(About Nicholas Roerich's art)

by H.A. Anil Kumar

When Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich (1874-1947) painted those innumerable Himalayan mountain ranges as images, over a stretch of his mature lifetime, he was always attempting to cross over the very mountains, beyond their real and metaphorical dimensions. Perhaps he was the initial diasopric Indian artist, much before Amrita Sher-gil¹ Nicholas Roerich was depicting the walls of India with its mythical past as its character. For the Europeans who depicted India it was a colonial expedition, and for the Russian it was a land of increasing uncertainty regarding the notion of home. May be he was painting from a side which was the wrong side, because home was what laid on the other side for him. He painted series of mountain scapes in India at Kulu, wherein currently a museum of his-self does exist.

When Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich (1874-1947) painted those innumerable Himalayan mountain ranges as images, over a stretch of his mature lifetime, he was always attempting to cross over the very mountains, beyond their real and metaphorical dimensions. Perhaps he was the initial diasopric Indian artist, much before Amrita Sher-gil¹ Nicholas Roerich was depicting the walls of India with its mythical past as its character. For the Europeans who depicted India it was a colonial expedition, and for the Russian it was a land of increasing uncertainty regarding the notion of home. May be he was painting from a side which was the wrong side, because home was what laid on the other side for him. He painted series of mountain scapes in India at Kulu, wherein currently a museum of his-self does exist.

Compare these mountains with Mont Sainte-Victoire that Cezanne painted and the Fuji Mountains based on which Katsushika Hokusai created the Ukiyo-e prints. Roerich was trying to do what the other two were not interested in doing. He was representing that which he wanted but could not overcome. For the other two the mountains were the very conclusive canvas of contemplation. They went around it, only to bring back visuality, to rest upon the mountains they painted. For Roerich, though the hilly ranges were availed with a certain contemplative rock solid objects, they are also seen as barriers that the artist would like to overcome, in his pictures. And his very painting seems to be the best remedy for that!

Instead of using the classic oil and canvases, he used tempera layers, wherein the layers were mutually distinct, even when perceived for aesthetic consumption. He excavated, documented and did all that a typical Orientalist in the early part of the twentieth century was so enthused to do, in and around the area that he painted. He painted the area that he had traversed or the ones he wished to, in the near future. It was as if to (a) record, (b) document and (c) measure-draw them. All these three are the ingredients of 'mapping' a place. Either the cultural mapping he was into was done before an excavation (as a 'plan') or afterward (as a 'diary'). Just like a travelogue concludes only after the visited places are appropriately documented, the land and mountains that he painted seem to  belong to a point wherein his anthropological sojourn would embark or conclude.

belong to a point wherein his anthropological sojourn would embark or conclude.

The mature painterly period of Nicholas Roerich was a period of tumultuous political upheaval that did not spare artists who wanted to contemplate upon those through cultural expressions (Naum Gabo, Pevsner, Chagall, Chaplin, Matisse and the like). However, though his seemingly ever lush colours in his paintings seems very iconoclastic, in the sense it seemed to belong to a classical Baroque tradition, they nevertheless along with his all other non-artistic, scientific preoccupation--yearned for a world which was utopian by nature. His writings and thought process believed in a unified ideal world based on cultural products. It was a world which was becoming more and more unrealistic, for, it seemed to be the result of a leisurely (but laboured) imagination of the elitist and the bourgeois, in an increasingly Marxist/leftist world ideology.²

Roerich's artistic biography is a network of visual travelogue, written from either the view point of an anthropologist or surveyed through the eyes of a painter. Like a Renaissance man, like Tagore, Tolstoy and Shivarama Karantha³ was he accumulating all that he had undergone, in the form of those mountain ranges, which look like theatre prop to the drama of his life? In his visual representation,  he perhaps adopted a representational device that was more mythological than contemporary. Tiny figures, incidents and village-scapes act as pins on a notice board, in his paintings, wherein mythology comes as an unspecified narrative of the contemporary, with a background of mountain ranges, which withholds its own yet another kind of narrative. The cultural response based on mythical characters, to a life threatening contemporary political upheavals beginning with exiledome, might be an attempt to construe a space of one's own that the political foes might not be able to decipher.

he perhaps adopted a representational device that was more mythological than contemporary. Tiny figures, incidents and village-scapes act as pins on a notice board, in his paintings, wherein mythology comes as an unspecified narrative of the contemporary, with a background of mountain ranges, which withholds its own yet another kind of narrative. The cultural response based on mythical characters, to a life threatening contemporary political upheavals beginning with exiledome, might be an attempt to construe a space of one's own that the political foes might not be able to decipher.

On the one hand the mythical figures in his pictures are also part of his yearning for the nostalgia, which is there to be recovered, in order to include them to his Urusvathi-like idealistic world. On the other, the brush strokes that form the mountains seems to be gestures to traverse through the artist's own hands, that he did or could not do (inclusive of both) physically across the geographical areas during his excavations, due to socio-political reasons and restrictions.

The logo that he designed for his ideal world, uniting people across the countries through cultural products (three red circles forming a Pyramid) were all derived during the time of the world wars. What you cannot solve in reality, you can reclaim it through cultural representation, seems to be the unfailing belief system that he had developed. The figuration in his works are theatrical, influenced by the Byzantine church in Russia (St.Petersburg, to be specific,  where one of the art school is named after him), and also insists upon a friendly neighbourhood comradeship between Russia and India, through linking of past narrative mode. Shergil and the current Diasporic Indian artists' artworks might consider a direct national narrative as banal, while Roerich relied much upon it.

where one of the art school is named after him), and also insists upon a friendly neighbourhood comradeship between Russia and India, through linking of past narrative mode. Shergil and the current Diasporic Indian artists' artworks might consider a direct national narrative as banal, while Roerich relied much upon it.

He was aware of his contemporary European Modernist art, but by heart was what those sympathizers of Modernity would term as 'romantic' at heart a la the Orientalist. In a way, the burden of nostalgic baggage affiliated to Roerich's kind of artworks becomes less if one realizes that the overall outlook of the Symbolists at the turn of the twentieth century was as existentialist as the French literary existentialism, though not lesser than that. The boat that carries the travelers from India, or the tribal people and similar other pictures by him hint at double or dual, juxtaposed narratives, willing to mutually differ from each other forever, just like the layers of wash tempera paint that he used are mutually distinguishable, even while perceiving his completed works. On one hand they were simple narratives of Asian myths and on the other, the myths were used as autobiographical analogies by the artist. Those who are on the move are yet to get something while they will be giving away what they already posses; and Roerich was always on the move.

succinctly. 14

Note:

1. Not many writers, working within academic premise, acknowledge any modernity before Indian artists before Bengal school and Shergil. The diasporic Shergil is held to be the 'protagonist' of certain tradition of east west and inter-nationalist relations. There could be yet another kind of art history provided if Shergil is treated as the 'conclusive point' of a certain art historical tradition. Roerich and the European artists of Company period precede her in the notion of Diaspora and representation. Parta Mitter's book 'Much Maligned Monster' gives a comprehensive account of early phase of diasporic travelogue and representations. An interesting point is how an Italian artist represented the Indian Coromondal dancers, down south, based on the description by a traveler. The artist himself had never been to India. Also, it was a regular habit to graphically depict Indian monuments as a part of archaeological survey and convert them into watercolours, or vice versa, back in London in the form of book-editions by other artists who had not visited India.

Nicholas Roerich was depicting the walls of India with its mythical past as its character. For the Europeans who depicted India it was a colonial expedition, and for the Russian it was a land of increasing uncertainty regarding the notion of home.

Only in such circumstance will Nicholas Roerich be considered within the Indian diasporic discourse, just like his son Svetoslav Roerich will be considered within the history of Karnataka modern art.

2. A latter case similar to this is arguably the philosophy of novelist Ayn Rand, F. Kapra.

3. I am deliberately cross referring to personalities who do not gel well in the given framework of cultural epistemology. However, I heard a talk by Ramchandra Guha in Bengaluru, wherein he placed Dr.Shivarama Karantha, the Jnanapeet awardee above Rabindranath Tagore, the Noble Laureate, ten years ago; and in a lighter tone, said,” after writing this sentence, I am yet to go to Calcutta”.//