- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Musings from Chennai

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

June - July 2011

by Vaishnavi Ramanathan

This month's Musings from Chennai will look at the works of Rajendran whose works present an interesting case on tradition and its creation. Rajendran was an artist belonging to the Irula tribe of the Nilgiris, a tribe known for its skill in catching rats and snakes. A few decades back the tribe was relocated to Chenglepet district near Chennai. Around the year 2000, Dakshina Chitra, a heritage centre in Chennai conducted an artistic experiment to understand if the Irulas might have had a visual art tradition which might have subsequently been lost during this migration. So art materials were provided to Irulas and as a result a few artists emerged, the most significant being Rajendran1.

This month's Musings from Chennai will look at the works of Rajendran whose works present an interesting case on tradition and its creation. Rajendran was an artist belonging to the Irula tribe of the Nilgiris, a tribe known for its skill in catching rats and snakes. A few decades back the tribe was relocated to Chenglepet district near Chennai. Around the year 2000, Dakshina Chitra, a heritage centre in Chennai conducted an artistic experiment to understand if the Irulas might have had a visual art tradition which might have subsequently been lost during this migration. So art materials were provided to Irulas and as a result a few artists emerged, the most significant being Rajendran1.

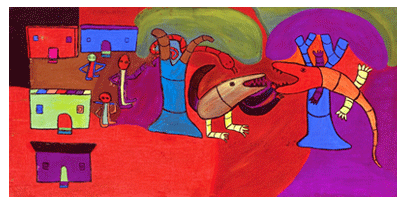

Rajendran's vivid paintings range from personal narratives such as drawings of his dream home to 'community'2 narratives based on the Irula life of capturing reptiles. These narratives are often structured along a diagonal or an undulating line that cuts across the picture space. This along with the predominant use of primary colours creates a sense of dynamism in the works.

Viewing Rajendran's works for the first time one is struck by the size of the animals and reptiles represented.  On closer look, the figures accompanying the reptiles become visible. However, the recognizable narrative of man dominating nature or vice-versa is subverted here since man not only slips between the role of the hunter and the hunted but at times even negates both roles by peacefully coexisting with the reptiles. The space in his painting is also very unique since it plays with the dualities of fantasy and reality- that is, the assumption that the creatures in Rajendran's paintings are purely fantastic or they are expressionistic depictions of the reptilian world around. However, these paintings point towards a third possibility; a viewer, who is unfamiliar with animals might 'imagine' that what he/she is seeing belongs to a 'reality' that he/she is not familiar with, even when the figures may actually be from the artist's imagination.

On closer look, the figures accompanying the reptiles become visible. However, the recognizable narrative of man dominating nature or vice-versa is subverted here since man not only slips between the role of the hunter and the hunted but at times even negates both roles by peacefully coexisting with the reptiles. The space in his painting is also very unique since it plays with the dualities of fantasy and reality- that is, the assumption that the creatures in Rajendran's paintings are purely fantastic or they are expressionistic depictions of the reptilian world around. However, these paintings point towards a third possibility; a viewer, who is unfamiliar with animals might 'imagine' that what he/she is seeing belongs to a 'reality' that he/she is not familiar with, even when the figures may actually be from the artist's imagination.

Often the idea that one has seen the kind of images in Rajendran's paintings somewhere yet nowhere arises.  This is evident in the common reaction to ascribe these works to an elsewhere space, that of other tribal traditions that one is more familiar with3. Perhaps this brings to the fore the issues related to a 'contemporary tribal artist' with regard to the individual and the establishment of a community style. While Rajendran like Jangrah Singh Shyam died young, he did so before he could establish an 'Irula style' of painting. The position of Rajendran's oeuvre perhaps points to the disparate role that death plays in the life of an artist. While the death of a 'contemporary artist' alters evaluative standards used to understand his/her work- increased prices and a need to document his/her body of works, the death of an artist associated with a community, before the establishment of a 'tradition' often creates a form of amnesia and a queasiness about locating the artist's works.

This is evident in the common reaction to ascribe these works to an elsewhere space, that of other tribal traditions that one is more familiar with3. Perhaps this brings to the fore the issues related to a 'contemporary tribal artist' with regard to the individual and the establishment of a community style. While Rajendran like Jangrah Singh Shyam died young, he did so before he could establish an 'Irula style' of painting. The position of Rajendran's oeuvre perhaps points to the disparate role that death plays in the life of an artist. While the death of a 'contemporary artist' alters evaluative standards used to understand his/her work- increased prices and a need to document his/her body of works, the death of an artist associated with a community, before the establishment of a 'tradition' often creates a form of amnesia and a queasiness about locating the artist's works.

1ExC-Sites of Recurrence, Madras Craft Foundation, 2003

2The dominance of reptilian forms in his paintings not only speaks of the importance of these animals in Irula life and history but also points to the artists referring to another tradition; that of films such as Godzilla, Jurassic Park etc. that would have been available to these artists in the form of dubbed films. Thus the community narrative that Rajendran draws upon is also one that extends outside the 'community'.

3Rajendran's paintings address viewers in different ways. The perception of these paintings by a person with a rural background or with an interest in animals would be different from a person who is unfamiliar with animals. Yet when Rajendran's paintings are viewed in association with the Irula community, the reaction to the works is in many ways similar, since the 'layman' as well as well as those familiar with the Irula community are unaware of the existence of an 'Irula art tradition'.

Images Courtesy: Collections of DakshinaChitra