- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

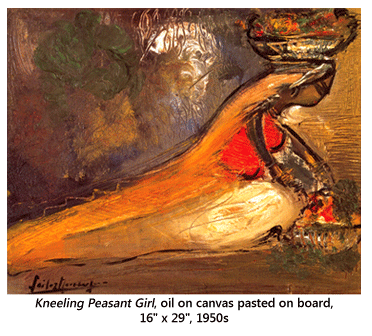

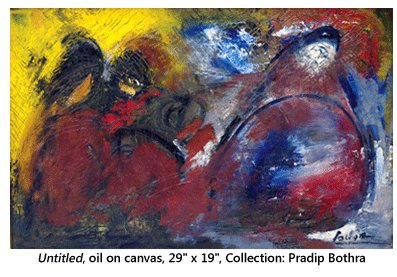

Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

by Keshav Malik

The year, I believe, is 1944, and we, I mean Ramkumar (later to be a full-fledged painter) and myself are still studying. He is studying economics and I am bravely struggling with my intermediate. Brain-wave and both of us find ourselves enrolled in Ukil School of Art on Queensway (later Janpath). Our art instructors are an amiable lot - there were three or four of them. And they taught us over the weeks to draw a skimpy chaprasi, complete with loin-cloth. The man is made to change his postures like a dancer. Sometimes he is seated, looking morose, on a shaky wooden stool and at another moment he is standing with one leg on floor and the other on stool. Well, his pantomime is in tact on my mind till date tickling a funny bone but also bringing on a sense of guilt. How we exploit the poor, for the matter of glorifying the art!

He is studying economics and I am bravely struggling with my intermediate. Brain-wave and both of us find ourselves enrolled in Ukil School of Art on Queensway (later Janpath). Our art instructors are an amiable lot - there were three or four of them. And they taught us over the weeks to draw a skimpy chaprasi, complete with loin-cloth. The man is made to change his postures like a dancer. Sometimes he is seated, looking morose, on a shaky wooden stool and at another moment he is standing with one leg on floor and the other on stool. Well, his pantomime is in tact on my mind till date tickling a funny bone but also bringing on a sense of guilt. How we exploit the poor, for the matter of glorifying the art!

Along with this modeling we were also made to copy Ajanta figures, often female ones, for days. The teachers would guide our erring pencils and then peer over our shoulders. This stint must surely have been our true initiation into the mysteries and delights of culture. The sensuous female torso toyed with, though only on paper, with complete detachment. A learning of the imagination indeed! Not quite clinical, but close to it. We were bewitched by the Ajanta hair-dos and the rich ornamentation from an age of abandon and the seemingly spontaneous mingling of men and women in gatherings and also with their meditative inwardness at other moments. All this is surely far distant from our patriarchal, dry as dust, morality; the cramped life space. We, at least I, found the Ajanta images suffused with the feminine principle, and thus awing in their very naturalness.  Yet, paradoxically, those who then follow in the steps of Ajanta, by sheer contrast, appear unreal, un-convincing. The imitating of hand gestures, of the mudras, and the headgears in our hands become cloying, merely arty. But since we are told that Ajanta is true art, we fall in line quietly. But something still tells us that the Ajanta spirit has to be pursued, though in a different way.

Yet, paradoxically, those who then follow in the steps of Ajanta, by sheer contrast, appear unreal, un-convincing. The imitating of hand gestures, of the mudras, and the headgears in our hands become cloying, merely arty. But since we are told that Ajanta is true art, we fall in line quietly. But something still tells us that the Ajanta spirit has to be pursued, though in a different way.

On such a scene comes a welcome disturbance, may be a monkey wrench thrown into our timid spirits. It is Sailoz Mukherjea. Among the other gentle souls he is the one whose postures are most intriguing but nonetheless entirely refreshing. There is yet boyishness intact in his full grown manhood.

Well, all in all here appeared a Guru whose wards were more likely to be like his pals. Yes, who of us would not have fallen for his charms? Given his overall life stances ours too underwent a secret mutation. Here was a friend in need in the guise of a drawing master. We leeched to the man even as we showed full respect to the other teachers. Sailoz however was a magnet and we like pins easily gravitating towards him; he then instilling us with an unknown fizzy freedom.

like pins easily gravitating towards him; he then instilling us with an unknown fizzy freedom.

And yes, out of school too he would often accompany us to the adjoining Coffee House, and we excitedly were doting on his words which never ever were pedantic. Not the usual authoritarian, we loved the ease in his speech. Oh, he had been to Holland! But this fact alone cannot have formed his life style, or his non-dogmatic opinions. There was some singular plasticity to his behavior but on which I am still not able to place a finger. At any rate here was one, a senior, who one loved and admired but whose feet one didn't touch as per given routine. Sailoz liberated us. He just would not be wooden in any sense of the term. A free bird he was, of great alacrity, the wings of his spirit sweeping back and forth and thereby unwittingly fanning the air in the fetid atmosphere to a brisk breeze. This was his true teaching, the manner in which his thoughts were presented.

His works are therefore celebratory, exuberant. He rejoiced in common and that is rural-life, despite the sophistication of his trained mind. He rebuffed intellectual snobbery of whatever kind. A modern with a heart- at long last! A rare thing indeed! Never stiff, his hallmark was his uncontrollable spontaneity. No unruly rebellion for him, as amongst self-conscious painters. His natural wisdom as well as his authenticity was totally uncorrupted by the present-day commerce or by stale convention.

No unruly rebellion for him, as amongst self-conscious painters. His natural wisdom as well as his authenticity was totally uncorrupted by the present-day commerce or by stale convention.

The impersonality of his craft had nonetheless the sharp profile of his own personality. The vitality of his work is suffused with the deeper individuality.

Sailozda's verve infected all those who came in touch with him. After Ukils, he was at the polytechnic, and in especial at the Carlton's Café at Kashmiri Gate. As for his choice works, they possess a latent energy. His human figures were robust, but unsentimental. His brush strokes are always bold, and simple that carried conviction. Racy and spontaneous, the wind of freedom still blows in his compositions.