- Prelude

- Editorial

- A time to Act

- Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

- Rabindranath as Painter

- Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality

- Abanindranath Tagore: a reappraisal

- Where Existentialism meets Exiledom

- Nandalal Bose

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- Sailoz: The Inerasable Stamp

- Amrita Sher-Gil

- Calcutta's Best Kept Secret: The Marble Palace

- Art is Enigmatic

- A few tools to protect the French culture

- The exact discipline germinates the seemingly easiness

- Symbols of Monarchy, power and wealth the Turban Ornaments of the Nizams

- The Bell Telephone

- The Pride of India

- Tapas Konar Visualizing the mystic

- Theyyam

- Our Artists vs. their Artists

- Dragon boom or bubble?

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata: May – June 2011

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Raja Ravi Varma: The painter who made the gods human

Volume: 3 Issue No: 18 Month: 7 Year: 2011

Art Treasures

by Nanak Ganguly

For the students of Art History and the followers of Indian Art, the name Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) has been familiar for more than one century. He was born in Kilimanoor in Kerala.  There was no immediate traditions which could inspire him and help him to evolve, Raja Ravi Varma broke new ground and left a brilliant legacy of academic realism. In the matter of skill and workmanship, he remains unsurpassed even today. He appeared at a historical time when “for the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie which arose within the colonial context” writes Eijaz Ahmed, “ the nation was a convenient site at which to construct their own hegemonic projects, in opposition to colonialism but also to displace the preceding and existing pluralities of indigenous society”. The arrival of Raja Ravi Varma's oleographs into the scene coincided with the construction of new cultural elite the arbiters of middle class taste. Born to the ruling family of Kilimanoor, a small estate in the erstwhile kingdom of Travancore, this aristocrat painter of myths with a high surface gloss became a cultural icon whose popularity acquired a pan- Indian sweep. Ravi Varma had two German experts to help him in the Lithographic press to meet the demands of his oeuvre. They were Schleicher and P.Gerhardt. From them the artist learnt German. The pictures that came out of the lithographic press reached as far as South Asia, Europe, Africa, and other places. The opening up of Ravi Varma Fine Art Lithographic Press in Bombay in 1893 lured quite a number of young stragglers just out of Sir J.J. School of Art. The production in the Press started a year later and among the many promising artists that worked in that Kalbadevi property included M.V Dhurandhar and the father of Indian Cinema Dadasaheb Phalke. Ravi Varma's

There was no immediate traditions which could inspire him and help him to evolve, Raja Ravi Varma broke new ground and left a brilliant legacy of academic realism. In the matter of skill and workmanship, he remains unsurpassed even today. He appeared at a historical time when “for the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie which arose within the colonial context” writes Eijaz Ahmed, “ the nation was a convenient site at which to construct their own hegemonic projects, in opposition to colonialism but also to displace the preceding and existing pluralities of indigenous society”. The arrival of Raja Ravi Varma's oleographs into the scene coincided with the construction of new cultural elite the arbiters of middle class taste. Born to the ruling family of Kilimanoor, a small estate in the erstwhile kingdom of Travancore, this aristocrat painter of myths with a high surface gloss became a cultural icon whose popularity acquired a pan- Indian sweep. Ravi Varma had two German experts to help him in the Lithographic press to meet the demands of his oeuvre. They were Schleicher and P.Gerhardt. From them the artist learnt German. The pictures that came out of the lithographic press reached as far as South Asia, Europe, Africa, and other places. The opening up of Ravi Varma Fine Art Lithographic Press in Bombay in 1893 lured quite a number of young stragglers just out of Sir J.J. School of Art. The production in the Press started a year later and among the many promising artists that worked in that Kalbadevi property included M.V Dhurandhar and the father of Indian Cinema Dadasaheb Phalke. Ravi Varma's  “Saraswati” and “Lakshmi” became the two most popular prints ever produced in India. Raja Ravi Varma became a household name. It influenced Indian Cinema and people who pioneered it-the 'Indianness' label in Phalke who was his acolyte, came to perform a role similar to Ravi Varma's naturalist freeze: providing a standpoint from which, against which, the images could be mediated into the present, that is, into cinema in the latter years. In Ravi Varma's painting the tableau-like quality draw our attention to use of models and photographs. “The tableau delivers what Barthes calls above the essence of the image, which is presumably iconic, into the arena of narrative. That is particularly relevant for Indian pictorial tradition as this transit into the modern.” (Geeta Kapur)

“Saraswati” and “Lakshmi” became the two most popular prints ever produced in India. Raja Ravi Varma became a household name. It influenced Indian Cinema and people who pioneered it-the 'Indianness' label in Phalke who was his acolyte, came to perform a role similar to Ravi Varma's naturalist freeze: providing a standpoint from which, against which, the images could be mediated into the present, that is, into cinema in the latter years. In Ravi Varma's painting the tableau-like quality draw our attention to use of models and photographs. “The tableau delivers what Barthes calls above the essence of the image, which is presumably iconic, into the arena of narrative. That is particularly relevant for Indian pictorial tradition as this transit into the modern.” (Geeta Kapur)

Since his acclaim at the Fine Arts Society Exhibition in Madras, 1873, he has been in the limelight and art critics and historians have sought to assess his role in the modern phase of Indian Art, and some erroneously on cheap oleographs rather than on his original paintings. Some historians such as Vincent  Smith had got facts mostly erroneous. Smith observes “the most representative of the Europeanized school of Indian Artists as the late Raja Ravi Varma of Travancore- a connection of the Maharaja of that State…..He had received instruction from Theodore Jensen and other European artists.. as well as from Alagiri Naidu, a native of Madurai in Madras Presidency. “The nature of the connection between Ravi Varma has been referred above , that the artist was no Raja and Jensen did not instruct him either; he only allowed him to watch him paint though there is an element of allegorical sketches in Deepanjana Pal's recently published book titled “The Painter- A Life of Ravi Varma.” It is also nowhere on record if Ravi Varma had any other European Masters, nor could have received any instruction from Alagiri Naidu. (This has been discussed in detailed accounts in Raja Ravi Varma by E.M.J. Venniyoor. Govt. of Kerala. 1981).

Smith had got facts mostly erroneous. Smith observes “the most representative of the Europeanized school of Indian Artists as the late Raja Ravi Varma of Travancore- a connection of the Maharaja of that State…..He had received instruction from Theodore Jensen and other European artists.. as well as from Alagiri Naidu, a native of Madurai in Madras Presidency. “The nature of the connection between Ravi Varma has been referred above , that the artist was no Raja and Jensen did not instruct him either; he only allowed him to watch him paint though there is an element of allegorical sketches in Deepanjana Pal's recently published book titled “The Painter- A Life of Ravi Varma.” It is also nowhere on record if Ravi Varma had any other European Masters, nor could have received any instruction from Alagiri Naidu. (This has been discussed in detailed accounts in Raja Ravi Varma by E.M.J. Venniyoor. Govt. of Kerala. 1981).

“…our days and nights were eloquent with the stately declamations of Burke, with Macaulay's long rolling sentences, discussions centered upon Shakespeare's dramas and Byron's poetry and above all, the large headed liberalism of nineteenth century English politics” (Tagore on the time of Raja Ravi Varma).

That fear of the unknown has been complemented in recent decades, by a fear of the known, one manifestation in writing of the famous “cultural cringe”. The Raja Ravi Varma retrospective at National Museum, New Delhi in May- June 1993, eighty seven years after his death aroused many a debate critiquing its ethical, cultural and political issues as a part of a larger political design of the state's intention to rehabilitate the painter with state honours, especially after December 6 in 1992. The critics and cultural theorists questioned of his becoming a cultural icon whose popularity acquired a pan-Indian sweep. Even Abanindranath said  “It is rare to come across in these days men like him, lovers of India like him”. But the cultural theorists feared that Ravi Varma's vision of Hindu- India as an 'ideal' is now being pushed towards a hardened fascist vision is obvious. Anita Dube, a contemporary practitioner remarked “It does not make him a fascist artist. Yet his lineage, from Phalke to B.R. Chopra, culminated in the Rath Yatra and the razing of Babri Masjid is certainly a matter of concern”. The painter was accused to have flattered the 'taste' of his predominantly Hindu patrons, what Ravi Varma depicted was a vision of civilization of the classical times, the mythic Golden Age, when Hindus were said to be at the peak of their powers-supreme and pure, both politically and culturally. The critics questioned “What was the nature of his enterprise within the larger construction of the Indian nation? What does his representation of women indicate? And does his resurrection within this particular hour of history mean? Geeta Kapur argued “ideologically speaking, the classical past is set against the medieval, which is regarded as having corrupted by a medley of foreign influences and by the psychology of subordination showing up a Hindu civilization…..” and that the State for being part of such designs, like the exhibition to become a cultural propaganda is plain and simple. That such design needs powerful icons, cult figures around which masses can be mobilized and encouraged to be uncritical. Do not forget even after two decades of the retrospective the popularity seems to remain unabated. The disjuncture with the past in the colonial was sought to be overcome by Ravi Varma through a facile appropriation of his own history within a typical, closed but 'high' and 'ideal' system in which the use value of myth was enormous even as a new myth, that of bourgeois eternity and naturalness was being formed.

“It is rare to come across in these days men like him, lovers of India like him”. But the cultural theorists feared that Ravi Varma's vision of Hindu- India as an 'ideal' is now being pushed towards a hardened fascist vision is obvious. Anita Dube, a contemporary practitioner remarked “It does not make him a fascist artist. Yet his lineage, from Phalke to B.R. Chopra, culminated in the Rath Yatra and the razing of Babri Masjid is certainly a matter of concern”. The painter was accused to have flattered the 'taste' of his predominantly Hindu patrons, what Ravi Varma depicted was a vision of civilization of the classical times, the mythic Golden Age, when Hindus were said to be at the peak of their powers-supreme and pure, both politically and culturally. The critics questioned “What was the nature of his enterprise within the larger construction of the Indian nation? What does his representation of women indicate? And does his resurrection within this particular hour of history mean? Geeta Kapur argued “ideologically speaking, the classical past is set against the medieval, which is regarded as having corrupted by a medley of foreign influences and by the psychology of subordination showing up a Hindu civilization…..” and that the State for being part of such designs, like the exhibition to become a cultural propaganda is plain and simple. That such design needs powerful icons, cult figures around which masses can be mobilized and encouraged to be uncritical. Do not forget even after two decades of the retrospective the popularity seems to remain unabated. The disjuncture with the past in the colonial was sought to be overcome by Ravi Varma through a facile appropriation of his own history within a typical, closed but 'high' and 'ideal' system in which the use value of myth was enormous even as a new myth, that of bourgeois eternity and naturalness was being formed.

I cannot help quoting Prof R. Sivakumar from his essay “The Home and The world in Ravi Varma” in the catalogue brought out during the above retrospective he writes “Ravi Varma's reputation largely rests on his appropriation of the Western academic style for the representation of Indian mythological themes. Strictly speaking he was not the first or the only artist to do so, but he set the ultimate standard and became the archetypal artist of this kind,  the master who best typified the tendencies of his times. His early success at the exhibitions and the national acclaim it brought, was somewhat offset by the harsh criticism of Havell and Coomaraswamy. His reputation has since then risen and fallen with currents in our ongoing debates on nationalism.”

the master who best typified the tendencies of his times. His early success at the exhibitions and the national acclaim it brought, was somewhat offset by the harsh criticism of Havell and Coomaraswamy. His reputation has since then risen and fallen with currents in our ongoing debates on nationalism.”

E. B. Havell says” Though not trained in a school of art, all his (Ravi Varma's) methods have been based on the academic rostrums of Anglo-Indian schools, fine Arts societies and art critics' and G. Venkatachalam, discussing the state of Art during the latter half of XIXth century, says” Painting, as such, there was none worth the name except the mogrelised type imposed by the Government Schools of Art, of which Raja Ravi Varma was the best example.'. Ravi Varma had nothing to do with art schools at any point of time. The Madras Art School was founded in 1853 and the Calcutta School in 1854, and for many years both of them had taught only industrial crafts. When painting, as high art as it was introduced as an additional discipline, during the late 1870's Raja Ravi Varma was already an accomplished painter. And his paintings emerged as the first important signifiers of 'modernity' and 'nationality', the notion of modernity, by then, was fully appropriated with the agenda of Indian nationalism. Dr . Anand Kentish Coomaraswamy's criticism was not based on his originals but on his oleographs. He had not seen the originals “I have not even seen the painter's work, and known it only from coarse prints.” The clue to the interpretive process in his work starts from the fact that the portrait, a privileged form of European and therefore colonial Indian art, is mapped over an indigenous albeit popular iconicity. Ravi Varma's references for this came from Tanjore paintings with their more elaborate Mysore antecedents, but these are superseded by what he learns of western manner in the easel format in Trivandrum.

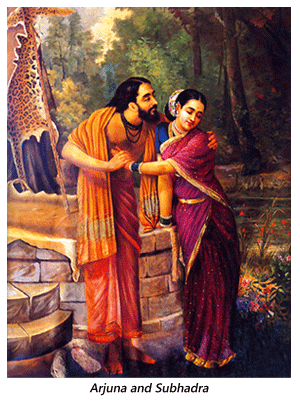

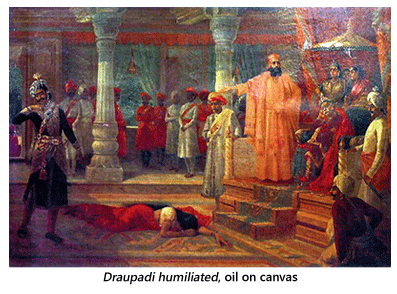

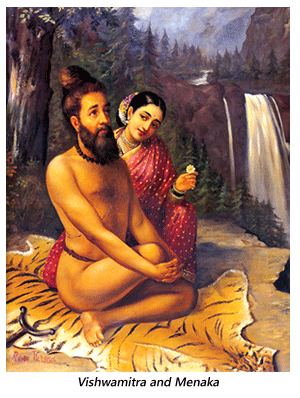

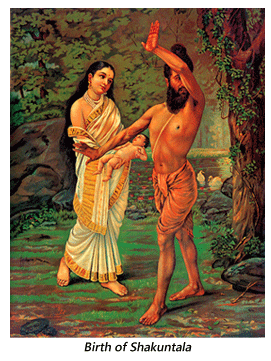

“That he was an artist en rapport with world in which he was living has been noticed both by his admirers and detractors” writes Sivakumar. “...  his sensibility has been seen as naturally and fully responsive to the taste of the contemporary native rulers and the rich westernized gentry. As one catering to their taste he is often seen as a product of this patronage. That in a sense he was, but before he was consciously responding to it and allowing himself to be moulded by it, he was motivated in that direction by some very home breed values”. Prof. Sivakumar's assessment is true. Almost everything that Ravi Varma initiated has become the stock in trade of the mass arts, especially commercial cinema, is what speaks for his genius, the identification and concretization of the core ideological spaces on which the mass market in India was, and is structured and also at the same time shall remain a striking case study of academic art in India. The neo-classical nuances in his language converged with the elements of the contemporary Parsi and Marathi theatre of his times. His particular style has an underpinning of the iconic format; it offers in the second look a specific style of staging whereby the frozen vignette comes to have an allegorical impact. In “Arjun and Subhadrs”, Shakuntala”, 'Galaxy of Musicians”, “ Draupadi at the court of Virata”, Hamsa and Damayanti, Shakuntala Patralekhan, etc done in oil. The seemingly classical devolves into the category of popular realism. He was courted assiduously by the John Company as by the Indian Maharajas, whilst cheap oleographs of Hindu Gods and Goddesses hung in almost every household of that period. These prints, still an essential ingredient of popular culture, are derided as signs of Orientalism. Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh writes” His most interesting innovation lies in the choice of his themes. He virtually invented the visualization of the legends of Harischandra-Taramati, Shakuntala, Vishwamitra-Menaka amongst others, as there are hardly, if any, traditional prototypes of these. With a bias towards a theatric tableau and physical freezing of scene, he was adding a new dimension of portrayals of traditional narrative. Traditionally, a continuous narration had avoided the projection of a claimactic moment. In looking for new themes to paint, he seems to have unearthed from the ancient and medieval storehouse many of with a vast potential for the nostalgic sentimentalia the Indian middle class seemed craved for.,

his sensibility has been seen as naturally and fully responsive to the taste of the contemporary native rulers and the rich westernized gentry. As one catering to their taste he is often seen as a product of this patronage. That in a sense he was, but before he was consciously responding to it and allowing himself to be moulded by it, he was motivated in that direction by some very home breed values”. Prof. Sivakumar's assessment is true. Almost everything that Ravi Varma initiated has become the stock in trade of the mass arts, especially commercial cinema, is what speaks for his genius, the identification and concretization of the core ideological spaces on which the mass market in India was, and is structured and also at the same time shall remain a striking case study of academic art in India. The neo-classical nuances in his language converged with the elements of the contemporary Parsi and Marathi theatre of his times. His particular style has an underpinning of the iconic format; it offers in the second look a specific style of staging whereby the frozen vignette comes to have an allegorical impact. In “Arjun and Subhadrs”, Shakuntala”, 'Galaxy of Musicians”, “ Draupadi at the court of Virata”, Hamsa and Damayanti, Shakuntala Patralekhan, etc done in oil. The seemingly classical devolves into the category of popular realism. He was courted assiduously by the John Company as by the Indian Maharajas, whilst cheap oleographs of Hindu Gods and Goddesses hung in almost every household of that period. These prints, still an essential ingredient of popular culture, are derided as signs of Orientalism. Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh writes” His most interesting innovation lies in the choice of his themes. He virtually invented the visualization of the legends of Harischandra-Taramati, Shakuntala, Vishwamitra-Menaka amongst others, as there are hardly, if any, traditional prototypes of these. With a bias towards a theatric tableau and physical freezing of scene, he was adding a new dimension of portrayals of traditional narrative. Traditionally, a continuous narration had avoided the projection of a claimactic moment. In looking for new themes to paint, he seems to have unearthed from the ancient and medieval storehouse many of with a vast potential for the nostalgic sentimentalia the Indian middle class seemed craved for.,  This triggered off varied repercussions on the ensuing movements in (Indian) cinema”(-Ravi Varma in Baroda). When marketed on a larger scale, the paintings transformed and transferred to appropriate the technology of colour lithography with high surface gloss, at the Ravi Varma Lithographic Press established by him and which supported his brother Raja Raja Varma, other apprentices and technicians.

This triggered off varied repercussions on the ensuing movements in (Indian) cinema”(-Ravi Varma in Baroda). When marketed on a larger scale, the paintings transformed and transferred to appropriate the technology of colour lithography with high surface gloss, at the Ravi Varma Lithographic Press established by him and which supported his brother Raja Raja Varma, other apprentices and technicians.

K.B. Goel, noted critic deconstructs Varma's 'Jatayu Vadha' at Shri Jayachamrajendra Art gallery, Mysore. In the painting Ravana is a dark Dravidian, powerfully built coarse figure embodiment of malevolent forces forcibly abducting a fair, demure North Indian woman, Sita, whose refined, upper class sensibility is horrified at the killing of Jatayu- there the core convention of the rape- formula has been created, with the bad black man and the 'good' white woman. But Pal's book that I mention above evades such issues completely and gives us a compelling tale of a prince from Killimanoor, a small estate in Travancore who took the revolutionary step of being a painter. In the biopic she has remained faithful mainly to the information she has rifled through books, manuscripts, notes, articles and catalogues to recreate the story of our first celebrity painter and a genius. She has weaved a narrative made of part fiction and imagination introducing a new area in art writing. The Raja's early days in Travancore to setting up of Fine Art Press in Kalbadevi, Lonavala and Ghatkopar. “ I wanted my reader to feel that same sense of immediacy that I had felt when hearing about Ravi Varma and the people he knew. I wanted to tell Ravi Varma's story in a way that felt alive, was accurate, and drew the reader into his world whether or not they were interested in the beginnings of modern Indian art…..and I have been careful to keep that which has been recorded distinct from that which was imagined.”

E. M. J. Venniyoor in his monograph on Raja Ravi Varma gives an account of his visit to Calcutta, the then capital city “During his visit to Calcutta, Ravi Varma had the very pleasant experience of being honoured by some of the leading families in the capital city. Surendranath Banerjee, a patriot and orator, who was among those who received him at the railway station, is reported to have exclaimed “We have been waiting for you for long; now we won't let you go!” There was a reception for him at the Jorasanko house of the Tagore’s when a young man brought a few sketches and pictures printed by him for the Master to see. He studied the pictures and prophetically stated that he saw the signs of future greatness in him. And it proved even so, for that young man was the future Abanindranath Tagore”.

the then capital city “During his visit to Calcutta, Ravi Varma had the very pleasant experience of being honoured by some of the leading families in the capital city. Surendranath Banerjee, a patriot and orator, who was among those who received him at the railway station, is reported to have exclaimed “We have been waiting for you for long; now we won't let you go!” There was a reception for him at the Jorasanko house of the Tagore’s when a young man brought a few sketches and pictures printed by him for the Master to see. He studied the pictures and prophetically stated that he saw the signs of future greatness in him. And it proved even so, for that young man was the future Abanindranath Tagore”.

But the worries persist about not having the full set of cultural tools, or misreading the grandeur and magnificence as these apply to the painter. The work and legacy of the painter Raja Ravi Varma is an impressive reminder of the vitality of our arts, then and now. The introductions continue though and open up a fresh new discourse. It is though these various ways that Raja Ravi Varma still acquires a public presence, with his work and discussion that surround him.