- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

A Medley of Tradition

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

The block-printed legacy of Brigitte Singh

by Sonika Soni

The continuum of Indian traditions including the art of painting, block printing, and garment design embraces Brigitte Singh. As she patiently seeks the blessings of the goddess Saraswati, her perseverance in this continuum contributes fresh layouts and distinguished flavours. Brigitte Singh's atelier is found in the large open complex of a haveli in Amber, near Jaipur. Immediately recognizable are her selections of traditional techniques and the graceful image of Saraswati astride a swan which has become Singh's trademark.

Brigitte Singh is a world-renowned textile designer who touched down India in 1980. It was a sensitive period for the emerging Indian market, a time when new equations between ethnic and foreign commodities were coming to terms. Increasing tourism gave way to the development of souvenir culture, and thus local crafts were saved from extinction, especially after the fastening of the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972. According to Brigitte a healthy local market for handicrafts was just cropping up, usually offering ad hoc and mediocre objects.  This period was also decisive for the families and communities of artists and craftsmen. Many such families and communities, which could not withstand changing circumstances after the loss of royal patronage, had diverged from their traditional order. Conversely, other families and young people were adopting traditional crafts in order to sustain themselves in the changed conditions. This confusion within the crafts tradition manifested itself in both miniature paintings and textiles. Brigitte, who initially came to India with the intention of learning the traditional art of miniature painting, was quite favoured by these conditions. Brigitte's original hopes of learning the traditional art of miniature painting faced a long run of misfortune until she met the master painter Shri Ved Pal Sharma, 'Bannuji' and the art collector and connoisseur Kumar Sangram Singh of Nawalgarh. Brigitte got the basics of tradition plastered in her under the acute guidance of these two personalities who were then considered as the authorities on the subject. Brigitte's hold on the brush and her selection of motifs exemplifies the quality of training that she underwent. But after her training in miniature paintings, she chose block printing as her career option, wherein she exploited her painting skills with a novel approach. She was immensely supported by her late husband Surya Vijay Singh of Nawalgarh.

This period was also decisive for the families and communities of artists and craftsmen. Many such families and communities, which could not withstand changing circumstances after the loss of royal patronage, had diverged from their traditional order. Conversely, other families and young people were adopting traditional crafts in order to sustain themselves in the changed conditions. This confusion within the crafts tradition manifested itself in both miniature paintings and textiles. Brigitte, who initially came to India with the intention of learning the traditional art of miniature painting, was quite favoured by these conditions. Brigitte's original hopes of learning the traditional art of miniature painting faced a long run of misfortune until she met the master painter Shri Ved Pal Sharma, 'Bannuji' and the art collector and connoisseur Kumar Sangram Singh of Nawalgarh. Brigitte got the basics of tradition plastered in her under the acute guidance of these two personalities who were then considered as the authorities on the subject. Brigitte's hold on the brush and her selection of motifs exemplifies the quality of training that she underwent. But after her training in miniature paintings, she chose block printing as her career option, wherein she exploited her painting skills with a novel approach. She was immensely supported by her late husband Surya Vijay Singh of Nawalgarh.

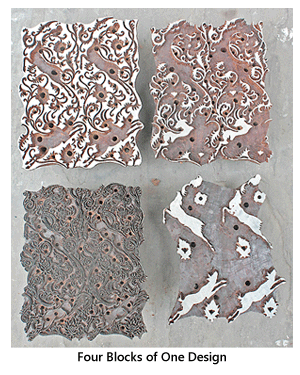

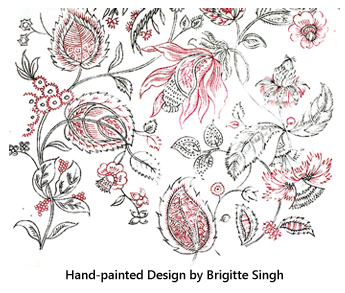

Painting and block printing in Rajasthan, as already stated, were part of living traditions. It was Singh's genius to realize the need of fresh inputs in both traditions in order to revitalize them. After the loss of courtly culture these traditions were hovering near stagnation. The commonly known forms of block printing, which were produced under the labels of Sanganer, Farrukhabad, Chhota Sanganer, Bagroo et al in Rajasthan, and also Paithapur, Jetpur and others in Gujarat, were quite distinguishable with their striking black-red-blue motifs and bold undefined lines. In block printing two or three wooden blocks of similar design but with different reliefs are immersed in colours and manually pressed (or thumped) on stretched cloth. Considered on a generic level, the splatter of colours and miss-punching of different blocks of the same design (off-register) is considered part of the traditional features. But for Brigitte, who was trained in the miniature painting tradition of precision and neatness, in which ultra-fine detailing and well-defined lines attest to the proficiency of the artist, she could accept nothing less than perfection. Singh was well aware of the fine specimens of block-printed cloths which master craftsmen had at one time produced for wealthy patrons in courtly times. Motifs in Brigitte's textiles are usually the floral and intricate entwined kunj. In India well-appreciated but pseudo naturalistic flowering plants have been favoured for royal paintings and costumes. Especially favoured and promoted by the Mughals, these patterns attained special status in the design departments of royal ateliers between the 16th to 18th centuries. The immense popularity of these motifs caused their simplified versions to surface in bazaar tradition. Their manifestations were of course to be seen in more popular block-printed textiles as well.

she could accept nothing less than perfection. Singh was well aware of the fine specimens of block-printed cloths which master craftsmen had at one time produced for wealthy patrons in courtly times. Motifs in Brigitte's textiles are usually the floral and intricate entwined kunj. In India well-appreciated but pseudo naturalistic flowering plants have been favoured for royal paintings and costumes. Especially favoured and promoted by the Mughals, these patterns attained special status in the design departments of royal ateliers between the 16th to 18th centuries. The immense popularity of these motifs caused their simplified versions to surface in bazaar tradition. Their manifestations were of course to be seen in more popular block-printed textiles as well.

Taking design references from these traditions, Brigitte undertakes the task of finalizing her designs after a series of chops, adding and changing details with her fine miniature painting brushes. She retains the quirky flow and 'jaan' (life) of these motifs as in miniature paintings. The finalized design is taken in the block-making section with the coordinators and the block makers who chip, press and chisel. They make three-four blocks as per the colour and lining requirements of each design. Considering the paradoxical requirement for both softness and stiffness in wood, usually teak and roida is used for this purpose. Great amounts of attention and exactness is employed while carving to ensure that the blocks last for the targeted amount of imprints, and also that the flow of the painted design is maintained in the blocks. Traditionally the worn blocks were never destroyed or re-carved, but were inserted in the walls of the home of the block maker. Keeping with this ritual, Brigitte cautiously preserves all of her old blocks.

Though Singh is inspired from the living tradition, she allows enough porosity between practice and tradition to achieve new results. Brigitte uses specially-made synthetic colours of varying shades and viscosity to match the needs of her technique and uses up to thirteen different colours for one print. Selection rests on a sombre and tertiary colour-scheme, with all the combinations and blending of tints finding the appropriate harmony. The nomenclature of her pigments…ranging from 'Jali Grey' to 'Krishna Leaf' to 'Haveli Sky', under colour collection tags such as 'Mughal Spring', 'Indian Summer' and 'Monsoon Rains' can evoke bewilderment. Singh's atelier maintains a separate colour-making unit where a carefully trained individual is in charge of making the desired tones and amounts of colour. After a series of sample printing, fine cotton clothes are stretched on long tables for final printing.  Not more than 50 meters of cloth is produced in a day, ensuring the intricacy and precision of the designs.

Not more than 50 meters of cloth is produced in a day, ensuring the intricacy and precision of the designs.

Long wooden tables are spread in a large hallway. This hallway is provided with large wire mesh windows and also huge chimneys that vent fumes emitted by the chemical pigments and also for direct light and temperature control as these hallways are liable to get warm because of the number of people working without fans. Breezes from fans can disturb the drying tendency of the pigments. Weather conditions are also a major factor in printing work. Late autumn, early spring, the tail end of the monsoon, and the very beginning of winter are the most desirable times for block printing. The entire printing process is like making a body filled with life through the prepared wooden blocks. This "life-filling" of the fabric comes with an interesting rhythm created by the thumping blocks. Block printing is a meditative process in itself, and it is done without diverged attention. Three or four sequential blocks are thumped with great precision to ensure that their accuracy is correct every time. Between the colour applications these long textile pieces are left to dry on ropes hanging over the tables. It is only after the final layer of colour that the cloths are dried in direct sun.

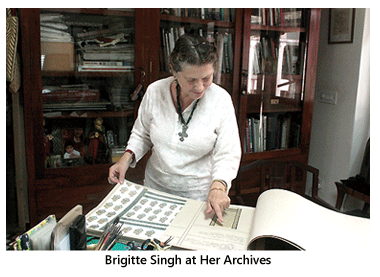

Brigitte Singh keeps a keen attentiveness to all of the work. Her haveli and atelier may sound like a dream from a royal tale, but all of that romance vanishes when one sees how dedicatedly Brigitte trains, supervises and ensures quality and precision. Work in the atelier doesn't end with printing. Brigitte enters the storehouse where all the prepared cloths are stored in lines of colourful thans. There she makes crucial selections of colours and designs for the production of various luxury furnishings, traditional costumes and accessories. After the selection of cloths, the cutting, drafting, sewing, filling, tagging and packing is done by the staffs, who are mostly women and young girls. They have been carefully trained to know that each and every stitch needs to be taken with great care to meet with the requirements of the overall aesthetics of the object. The garment line is a deliberate selection of tradition costumes ranging from choga to a line of traditional jackets including Burmese, Mughal, Nepali, Caracao and others. The most fascinating aspect of these printed clothes is the selection and designing of the patterns. Brigitte visits museums and historical places across the world to derive ideas; a huge library housed in her haveli also supplies her with the design references. All the butas (motif) used by her have been neatly archived, cataloguing the derivation and use of particular patterns in long files that are kept safely in a specially designed closet. Separate closets are provided for storing the samples of each and every draft and product made in her atelier. Brigitte provides a name to each buta that she finalizes. These names usually entail interesting stories, for instance Tara: this floral motif is named after the merchant 'Tarachand' by whom the design was first bought.

Brigitte visits museums and historical places across the world to derive ideas; a huge library housed in her haveli also supplies her with the design references. All the butas (motif) used by her have been neatly archived, cataloguing the derivation and use of particular patterns in long files that are kept safely in a specially designed closet. Separate closets are provided for storing the samples of each and every draft and product made in her atelier. Brigitte provides a name to each buta that she finalizes. These names usually entail interesting stories, for instance Tara: this floral motif is named after the merchant 'Tarachand' by whom the design was first bought.

Two popular myths are attached to Brigitte's body of work, one true and the other false. The first is that she uses only cotton cloths and the second is that her designs rest solely upon Mughal prototypes. She indeed uses only the finely woven cotton cloth for her printing, due to its friendliness to the chemistry of block printing (and also due to her personal likings for the cloth). But her patterns are not confined to Mughal motifs. She undertakes a range of references from 18th century French chintz (a word derivative from the Indian counterpart 'Chit'), to the motifs and colours found in wall paintings in the palaces of Rajasthan. Brigitte takes special care for the purification and re-use of chemically adulterated water generated by her unit. A water purification plant with a combination of traditional sand purification techniques has been set up between the lush lawns. The filters are traditional sand filters with an extra layer of vermin-compost full of micro-organisms, and also Canas plants with very powerful roots that actually digest the solid elements coming from the grey waters of the printing workshop. The cleaned water collected at the end is recycled in the gardens. This preventive measure displays Brigitte's consciousness, precision and working ethos. Technical diversity defines Brigitte's style of working. Right from the fashioning of a buta, Brigiette likes to play with the flow of the brush in a curious amalgamation of designs. This amalgamation mingles centuries and traditions, presenting brilliant hues in intricate patterns that are destined to adorn the best block-printed textiles. The tradition of painting and block printing has an undulating history of at least 4000 years. The contemporary blend of these traditions, shaped under the expert hands and 'terrible' rich eye of Brigitte Singh, makes for a medley of epochs in pleasing and happy notes.