- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Persistence of Anomaly

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

The creative journey of Srikanta Paul

by Moutushi

"I would repeat my trust in the contingent, the inauthentic, the whim, the practical - as strategies for finding meaning. I would repeat my mistrust in the worth of Good Ideas and state a belief that somewhere between relying on pure chance on the one hand, and the execution of a programme on the other, lies the most uncertain but the most fertile ground for the work we do." - William Kentridge

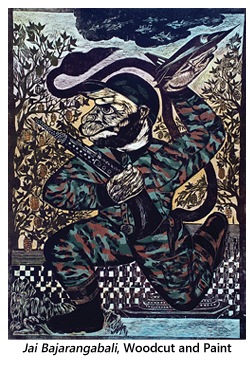

The artistic genre of Srikanta Paul stems from an unflappable rootedness of cultural inherit that concomitantly embraces the broader concerns of a globalised world with the conscience of a vagrant spectator.  Srikanta's expressionism reverberates with the philosophical connotations of the baul songs of native Bengal, weaving into it the historical-fantastical texture of mythological anecdotes; the crude realities of contemporary issues bordering on black satire. In his recent show titled Relevant/Irrelevant at Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai, Srikanta came up with a host of imageries distinctive in all their idiosyncratic renderings. Jai Bajrangbali presented to us the essence of this sensibility wherein the artist presents the iconic figure of Hanuman, a symbol of youthful vigor and blind loyalty. Embarking upon this as a reference point he ingeniously projects his Hanuman as a young gun-wielding military man replete in guerilla attire. Inhabiting the hostile world of fighter planes and grenade-bearing trees, this Hanuman, appears poised in his purposeful stance of duty. Sworn in allegiance by body and mind, he is a mere tool that facilitates a political endgame. With all his present day allusion Jai Bajrangbali epitomizes the socio-political concern of the artist. Interestingly, the works presented in Srikanta's Jehangir show were woodcuts printed on canvas painted over with acrylics and do not bear editions.

Srikanta's expressionism reverberates with the philosophical connotations of the baul songs of native Bengal, weaving into it the historical-fantastical texture of mythological anecdotes; the crude realities of contemporary issues bordering on black satire. In his recent show titled Relevant/Irrelevant at Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai, Srikanta came up with a host of imageries distinctive in all their idiosyncratic renderings. Jai Bajrangbali presented to us the essence of this sensibility wherein the artist presents the iconic figure of Hanuman, a symbol of youthful vigor and blind loyalty. Embarking upon this as a reference point he ingeniously projects his Hanuman as a young gun-wielding military man replete in guerilla attire. Inhabiting the hostile world of fighter planes and grenade-bearing trees, this Hanuman, appears poised in his purposeful stance of duty. Sworn in allegiance by body and mind, he is a mere tool that facilitates a political endgame. With all his present day allusion Jai Bajrangbali epitomizes the socio-political concern of the artist. Interestingly, the works presented in Srikanta's Jehangir show were woodcuts printed on canvas painted over with acrylics and do not bear editions.

In conventional terms one would be at a loss to categorize his works either as paintings or prints and perhaps this is what the artist unassumingly desires to be free of defined classification. By breaking away from the comfort zone of acceptance he manages to prioritize instead the visual content of his imagery. For artists like Srikanta conventionality or compartmentalization of an art form within the bounded limit of manifestation creates strictures within the art  practice that eventually override the primal focus of contextual profundity.

practice that eventually override the primal focus of contextual profundity.

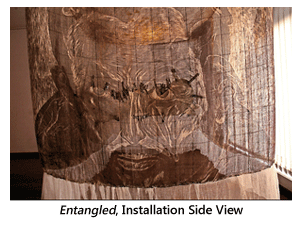

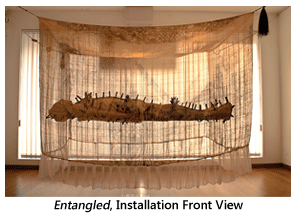

Hence the artist prefers to incorporate a personal vocabulary by embracing other nuances of creativity to represent his vision completely…a feat that is of no less significance, as it demands, manifold technical virtuosity. Srikanta's urge to straddle multiple genres for the fulfillment of his often angst-ridden expressionism has informed his art practice since his pedagogic years, when to achieve a desired texture he would prefer using a chisel hammer instead of the conventional woodcut tools or employ a gas-cutter machine to slice out a desired contour for his metal plate. As a part of the faculty in the Department of Printmaking at the Institute of Fine Art at Modinagar in Ghaziabad, he would encourage his students to print their imageries on the fabric of their garments thereby building a deeper connectivity with their individual art forms wherein the body, as a site of presentation, became its integral appendage. The very act of this transition of the printed surface from paper to cloth liberated the scope of his creative dimensionality by allowing him to exhibit his ideas at a more elaborate level of possibilities. This is exemplified by an installation work by him titled Entangled where he has printed his woodcut imageries on a semi-transparent muslin fabric which is then stitched and presented as a mosquito net. Inside this tent-like structure, placed on a transparent pedestal is a fiberglass body-mould of the artist himself, bandaged and held together with cloth clips. As the observer moves around the installation the imageries overlap with each other through the layers of fabric, spurting up a new metaphorical dimension with every passing angle. Entangled relates to its audience, the pining of an alert yet incapacitated being, entrapped within his domesticated dwelling where his soul begins to dry up with the inefficacy of his circumstances.

Inside this tent-like structure, placed on a transparent pedestal is a fiberglass body-mould of the artist himself, bandaged and held together with cloth clips. As the observer moves around the installation the imageries overlap with each other through the layers of fabric, spurting up a new metaphorical dimension with every passing angle. Entangled relates to its audience, the pining of an alert yet incapacitated being, entrapped within his domesticated dwelling where his soul begins to dry up with the inefficacy of his circumstances.

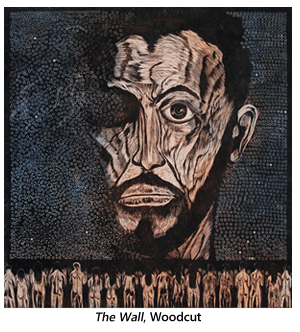

In several works, as in Entangled, the self-image of the artist stares back at the spectator with an uncompromising glare, in defiance of his stance, observing everything and dispensing nothing. As if in a lyrical representation of form this self-image recurs again and again within the frame of the artist's creative genus which he explains to be the presence of the common man, personified by himself, standing witness to the significant events of his time. This 'common man' enacting in the role of the 'conscience', sometimes looks inwards and at times outwards, to comprehend the import of the contemporaneous under-tide. In The Power Glass the artist represents himself as the curious onlooker, peering through a pair of binoculars, at the ironical events of his time. What he visualizes is a coercion of ideological values, where the protector turns to be the power-hungry eradicator. A comment on an unfortunate event of Nandigram in his native state, he manifests this abomination by the reflected clash of two iconic images of revolution Chittaprasad's bucolic uprising hailing communism and Goya's record of disastrous encroachment on 'The Third of May'. Here the 'home' and the 'world' unite in the intellectual horizon of the artist as he looks outside of himself at the human predicament. In another image titled The Wall after Alan Parker's 1979 film, the artist looks within himself for the courage to resist, even with a wounded body turned back defiantly with a single eye that refutes the statement 'an eye for an eye'.

sometimes looks inwards and at times outwards, to comprehend the import of the contemporaneous under-tide. In The Power Glass the artist represents himself as the curious onlooker, peering through a pair of binoculars, at the ironical events of his time. What he visualizes is a coercion of ideological values, where the protector turns to be the power-hungry eradicator. A comment on an unfortunate event of Nandigram in his native state, he manifests this abomination by the reflected clash of two iconic images of revolution Chittaprasad's bucolic uprising hailing communism and Goya's record of disastrous encroachment on 'The Third of May'. Here the 'home' and the 'world' unite in the intellectual horizon of the artist as he looks outside of himself at the human predicament. In another image titled The Wall after Alan Parker's 1979 film, the artist looks within himself for the courage to resist, even with a wounded body turned back defiantly with a single eye that refutes the statement 'an eye for an eye'.

Stylistically Srikanta's imagery evokes the tradition of Bat-tala prints that introduced the trend of commenting on present-day social issues within the framework of mythological referencing. Concurrently he also draws heavily on the urgent immediacy of German Expressionism and artists like Chittaprasad Bhattacharya and William Kentridge. In a conscious decision to proudly carry forward one of the most ancient techniques of printing, i.e. woodcut; Srikanta fosters the medium with élan, resolute in his defiance of the medium's present tag of 'unsaleability'. He continues his practice with a meditative resilience that he believes the medium of print illumines within him.