- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

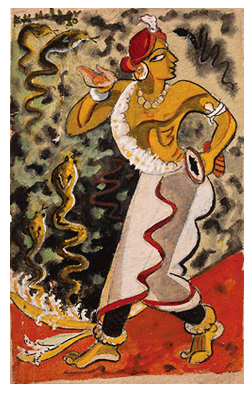

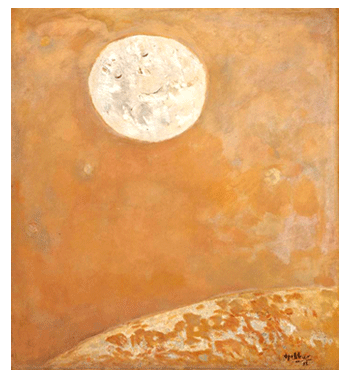

A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Review

Problematics of and alternatives for museumisation

by Anekha

Bengaluru: (I) Kattengeri Krishna Hebbar's (1911-1996) second retrospective show is being held at NGMA, Bengaluru, currently, which means that a formal 'national' endorsement of the artist by an official cultural institution has occurred posthumously. He was born in Karnataka, lived mostly outside of it in more than one sense and has returned back posthumously, that too for the second time, as a Karnataka artist. The last time he did so was when some of his works (not the best, though) were housed 'as' a permanent museum, inside an already existing museum consisting the major works of a very popular artist identified with Karnataka (K.Venkatappa) and a second one who remains to be a stranger to, arguably, one and all, even to this day (sculptor C.P.Rajaram). Devoid of even a simple informative leaflet, Venkatappa museum contains works that are mute to the visitors, most of whom are comparatively strangers to mainstream visual culture and are those who would appear from the neighboring, every busy Sir Vishveswaraya technological museum.

Venkatappa museum contains works that are mute to the visitors, most of whom are comparatively strangers to mainstream visual culture and are those who would appear from the neighboring, every busy Sir Vishveswaraya technological museum.

Owing to the fact that any and many attempts from both the authorities and artist community to make the museum(s) interactive, Venkatappa Museum (actually called as Venkatappa Chitrashaala) [1], the only State government run modern art museum in Bengaluru, along with Hebbar's works, gains audience only when the museum auditorium and galleries are rented out occasionally to the display of the works of lesser known artists.

In contrast, Hebbar's show at NGMA (Bengaluru) happens to be the first major retrospective of the artist within Karnataka State in which he was born into, and has been endorsed as such. The show is curated by Rajani Prasanna and Rekha Hebbartwo culturally talented daughters of the artist, hinting at a kind of famil(y)iar process of history of cultural legitimization.

(II) The Indian modernists can be geographically categorized into three kinds, owing to (i) their belongingness to a certain State or (ii) lack of it; and (iii) the new breed of the Indian Diasporic artists. The Bengal masters belonged,  Husain did not and Aneesh Kapoor belongs to the third category.

Husain did not and Aneesh Kapoor belongs to the third category.

Hebbar, in this sense, is connected to Karnataka with very few but decisive strings. The current year happens to be the centenary celebrations of the artist, which is, first of all, the appropriate and justifiable reason for holding the current retrospection. Hebbar's works from Venkatappa Chitrashaala is also shown here in newer light, in company with those from K.K.Hebbar Foundation, which might not be publicly available all the time. The problematics and the advantages of this retrospect are like a double edged knife. His position as a national artist, at least till now, seemed to be officially contested by not subjecting him to retrospection elsewhere outside Karnataka, despite Indian government having conferred Padmashree award to him a while ago. Hebbar is one of the many artists whose personality has been subject to such official paradoxical behavior meant specifically for visual artists.

Interestingly, Hebbar shares the centenary with a couple of his classmates from Chamarajendra Technical Institute (CTI), a Mysore princely Sate venture, which is currently known as CAVA School of art. Two of his class mates whose centenary is being celebrated by the Karnataka government do not enjoy this privilege of this scale of national official endorsement, despite one of them being a recipient of Padmashree accolade. B.H.Ramachandra and Padmashree S.N.Swamy were Hebbar's classmates at CTI. Interestingly, the Bengaluru NGMA is planning a retrospect of Rumale Chennabasappa, a landscape artist, editor and a freedom fighter, an alumni of Kalamandir School of Art (which began in 1919, a year before Kala Bhavana at Santiniketan was initiated) in December 2011, which makes the classification of these three artists much more hierarchical. The ad-hoc choices of 'nationalizing' artists by governing agencies narrowly escape being framed within deliberate nepotism.

Hebbar's artistic contribution has been duly acknowledged elsewhere. [2] My intention in this article is to contemplate upon the mode of museumisation of Hebbar, [3] the artist personality, than re-intervene into the representational talent which has been sufficiently acknowledged [4]

the representational talent which has been sufficiently acknowledged [4]

(III) The Venkatappa Museum (that housed K.Venkatappa's artworks along with Rajarao's sculptures) in Bengaluru was further squeezed to accommodate a museum for K.K.Hebbar in the year 2004, which was a State government venture. There seemed to be an urgency to monographically museumise the artist, superseding a few deserving artists (arguably Rumale Chennabasappa and R.M.Hadapad--the former being a freedom fighter and an editor of 'Thainaadu' then run by an educationist, M.S.Ramaiah, in whose name a chain of Medical, Engineering institutions exist, even to this day; and the latter being a maverich-pedagogue, who founded the Ken School of Art in Bengaluru.)

The artistic talent of these two artists lies in a deeper sense of belongingness to an art community immediately around them and whose works were appreciated, beyond the 'picture-as-art politics' of the Nation-State developing capital. Hadpad literally lived within Ken school of art, like, say, Ram Kinker at Santiniketan.

While one anonymous and two popular artists are thus officially museumised by the State authority, two others have been museumised by a private sector. Svetoslav Roerich, who had settled in Bengaluru and S.S.Kukke, another talent from CTI (Mysore) has been museumised at Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath museum clusters, in the form of 'collections'. The difference between collection and museumisation amounts to the degree of seriousness that is brought into one's creation. Amongst the four, Roerich has already been written off or to be more precise, never included in the regional art writing (Kannada) of Karnataka, S.S.Kukke has been forgotten (but for a monograph published by Karnataka Lalitkala Akademi), Venkatappa has been the most acknowledged by the State government while Hebbar has been the most acknowledged (though not critically) amongst the Kannada litterateurs Ku.Shi.Haridas Bhat has written a autobiographical book of around two hundred pages, Hebbar's drawings have been widely circulated as cover pages and space fillers amongst the serious, non-commercial literary discourse magazines in Kannada ('Shudra', 'Sanchaya', 'Sankula' among others).  The friendship between Hebbar and Jnanapeet awardee Tagore-like Shivarama Karantha has not only led to a lot of portraits of the latter by the former, but also informs a lot of contrasts between Hebbar-Karantha in the way both defined their representational devices and Hebbar-Yashwanth Chittala, a Kannada novelist, in the way both lived and represented Mumbai city wherein they spent most of their lives.

The friendship between Hebbar and Jnanapeet awardee Tagore-like Shivarama Karantha has not only led to a lot of portraits of the latter by the former, but also informs a lot of contrasts between Hebbar-Karantha in the way both defined their representational devices and Hebbar-Yashwanth Chittala, a Kannada novelist, in the way both lived and represented Mumbai city wherein they spent most of their lives.

(IV) Preceding this process of legitimizing the contribution of an artist was the act of museumising Hebbar. Two important incidents about Hebbar inform that the reasons for legitimizing KKH are because of (i) his non-controversial personality as well as (ii) democratic representational politics.

Having lived most of his painterly life in Mumbai, Hebbar's connection to Karnataka State was 'representational and signatory' rather than 'a lived-experience'. For him, the State was a nostalgic memory, that too in the form of one of its own folksy tradition of visual representation. In other words, Hebbar painted the nostalgia inherent within one of the several Districts of Karnataka Dakshina Kannada and the art form for which it is popularly known (Yakshagana, for instance).

Do the artists, through the way their personality is moderated, decide the fate of their museumisation? This is an out-of-the-box reversal of the otherwise criticism upon governing agency's (in)sensitivity not in archiving but the way it is done. Hebbar--like Roerich and unlike Venkatappa–belonged to the experience of Karnataka only through nostalgia and Diaspora, that too in a paradoxical context wherein those who did 'operate from within' are less privileged due to the lack of governing museumisation or have been subject to alternative modes of museumisations. Hebbar is lucky in more than one count, but for a critical evaluation, that evades even those of his colleagues like M.F. Husain. However, from a bird's eye viewpoint, the urgent need is to subject Hebbar to critical emancipatory process rather than a certain imprisonment within physical structures of nationalistic agenda. Carol Duncan rightfully brought in a comparison between the structures of museums and prisons. Artworks and people respectively reside in them (only) before or after a (value) judgment.//

(1) Hebbar received the prestigious Karnataka government award named after Varnashilpi K.Venkatappa Award in 1995, a year before his demise.

(2) Read article: Contesting National and the State: K.K.Hebbar's Modernist Project, H.A.Anil Kumar, February 2011 issue, published in art news & views, Emami Chisel Art Pvt Ltd, Kolkata. The article is also available online: www.artnewsnviews.com.

(3) The process in which S.N.Swamy, for instance, has already been museumisedif liminality is its effect, as Carol Duncan points outhint at the alternative process of museumisation that the 'lesser privileged' are destined upon. His pencil sketches of Karnataka sculptures, of National leaders and the like have been already published (since 1980s) and thus endorsed by the National Lalitkala Academy. Most of the hotels in Bengaluru have framed individual leaflets from those books, art school students treat it as a basic visual text to refer to while sketching, which are two of the many alternative, unofficial methodology of museumisation of a cultural personality, in a public domain. Hebbar, on the other hand, is the lucky one who has been the first and the only artist from Karnataka to be officially framed within the administrative outlook of democracy.

(4) Ref: Suresh Jayaram's dissertation on Hebbar, 1993, Department of Art History, Fine Arts Faculty, M.S.University, Vadodara; and the documentary about K.K.Hebbar, called Voyages in Images, directed by Girish Kasaravalli, 18 minutes, produced by the State Government. The film contains a couple of shots of the last days of Hebbar, was inappropriately delayed off its release, much after the artists demise. In this sense, official structure of museumisation of chosen artists seems to wait for special occasions like centenaries of those artists. This too has been a luxury for others like K.Venkatappa (himself!) and S.N.Swamy who are not even subject to such delayed privileges. Read: newspaper article Film on Hebbar languishes in the Cans (pun intended, perhaps), by Anita Rao Kashi, in Times of India, 20th May 1996.