- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

The Imprinted Body

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

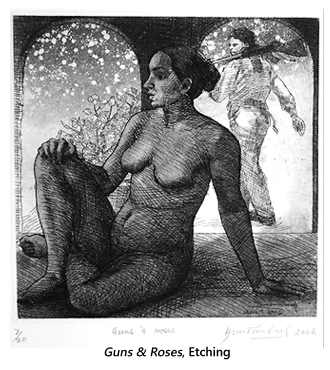

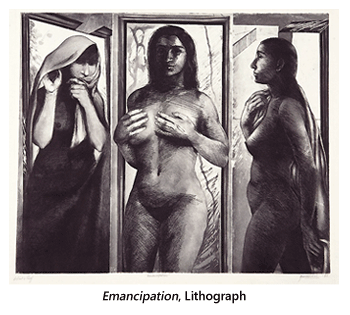

A reading of two seminal works by Anupam Sud

by Subba Ghosh

“Needs more polishing”, I said to myself. A blurred reflection was peering back at me, and the cold metal has to be polished until it reflects like a mirror. The first image to reflect will be your own. It is inevitable perhaps. Any image that resonates thereafter from the plate will always be an echo of the artist since it is impossible to detach one from the other. They are intertwined till death. The processes that shape the image on the plate are brutal;  the confrontation is intense and physical with the acid biting mercilessly into the body of the plate, the ink forced into the depths of its gaping wounds. You scrape and block, you etch and slash, until from this frenzied work a semblance of an image starts to emerge.

the confrontation is intense and physical with the acid biting mercilessly into the body of the plate, the ink forced into the depths of its gaping wounds. You scrape and block, you etch and slash, until from this frenzied work a semblance of an image starts to emerge.

It is birthing a reflection with a life of its own. It is an image that will be the artist and the other at the same time. The plate remains an enigma in the negative with the ink forced into the depths of the lacerations inflicted on it; until a pliant paper is laid gently over it and placed as an offering on the bed of the press. The rollers begin to grind, pulling the plate into its unforgiving embrace, releasing it onto the other side, lifting the ink from the plate and in the process transferring the image onto itself. What is imprinted onto the paper is not just an image suddenly put into perspective; a new world of signifiers is launched as well. There is always a moment of silence before the paper is peeled off the plate. A pause to wonder at the miracle of birth before the umbilical cord that connects the paper to the plate is cut. While the physical separation is inescapable, the metaphorical cord always remains. The plate is a womb that can still give birth to several such prints. All prints pulled from the plate may seem repetitions on the surface, but as they scatter and travel to inhabit different worlds they will come to acquire new meanings: enriching history and knowledge in a journey that they will come to inherit and create at the same time. The print's release into the temporal world is like the path of a migratory being,  possessing a life of its own that will result in countless encounters which in turn will lead to a thousand stories.

possessing a life of its own that will result in countless encounters which in turn will lead to a thousand stories.

The body; especially the woman's body, is at the centre of Anupam's entire pictorial thesis. The body of the woman is pitched as a site of political contention and social control, resisting any attempt to stereotype it as a fixed biological essence. Anupam has always maintained an emphasis on the women's experience as a prism to appreciate the full spectrum of her life and through it create a location that the body utilizes as a starting point for its own emancipation. The women in Anupam's gamut of work are mainly involved with daily routines in domestic surroundings or as critical presences in a chain of signifiers. It is this locus from where the power struggle acts itself out, exposing the everyday practices that sustain and reproduce the power relations between the genders. This politics is also congenital to our daily life that translates the social and sexual aspects of our body into a political phenomenon. The woman's body dominates the visual landscape in Anupam's vision, as she transforms the female nude to a feminine body by the subtle maneuvering of quotidian routine as a point of resistance to patriarchal domination.

Hello darkness, my old friend

I've come to talk with you again

Because a vision softly creeping

Left its seeds while I was sleeping

And the vision that was planted

in my brain

Still remains

Within the sound of silence

Lyrics from Simon and Garfunkel's The Sounds of Silence, 1964

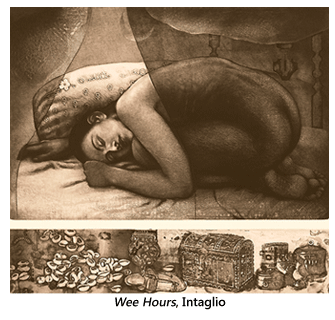

The stirring melody of Simon and Garfunkel's “Sound of Silence” haunts Anupam's intaglio titled Wee Hours. She envisions a darkness slowly enveloping the woman, shorn of clothes, as she recoils from the gathering blackness and curls up into a fetal position looking for the security of her mother's womb. The netting cascading down encompasses the bed like a cocoon. There is a heavy stillness in the air. A thick silence pervades this world as the passing moments seem to be inexorably slowing down. Her body is relaxed, a serene expression is on her countenance, maybe a hint of a smile even. Is she asleep, half asleep or half awake? But there is an impression that she has slipped into the world of dreams unnoticed and the weight of the world seems to have lifted from her shoulders. This is our inner world: a carefully, but not always consciously constructed sanctum sanctorum. Time has no meaning here. Fantasy rules the realm. There are no recriminations, no false moralities. Vision can be formed freely and destroyed easily. Memory and history have no meaning or chronology. There are no walls and borders are palimpsest. Space is unhindered, gravity has no meaning and infinity always seems to be within grasp. This is an alternative world we all hold within ourselves, a secret that we experience on our own terms whether waking or sleeping.

Curling up like a fetus makes this woman feel secure. Her tranquility is testimonial to the idea that for the moment she is at peace with the world. The dark shadows of the night slowly settle around her like an obscure film, partially dissolving the world into a darkness disrupted by a trace of shimmering light,  like a fading memory. The naked body dominates the space that glows with a light from within and partially alleviates the darkness. She has quietly carved out a space for herself and claimed it as her own, refusing to abdicate to the law of the dominion of darkness. It is like the noble and uncompromising rebellion of Antigone that had ruptured the walls of King Creon's kingdom and defied the word of her father (Jacques Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, Seminar 7, 1959-60). Anupam is very emphatic about not being an overtly militant feminist. The images she inscribes are all located within her life experience. Life as experienced by a woman. This relentless claiming of the space and the identity, and the uncompromising articulation of the woman's experience has all the characteristics of a political resistance within the constraints of a hegemonic patriarchal system. It is important to note that the passivity of the sleeping figure is deceptive, because the inner world that she has created is her own, constructed out of her own desires, and with this unambiguous expression she lays claim to the right to reinvent it.

like a fading memory. The naked body dominates the space that glows with a light from within and partially alleviates the darkness. She has quietly carved out a space for herself and claimed it as her own, refusing to abdicate to the law of the dominion of darkness. It is like the noble and uncompromising rebellion of Antigone that had ruptured the walls of King Creon's kingdom and defied the word of her father (Jacques Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, Seminar 7, 1959-60). Anupam is very emphatic about not being an overtly militant feminist. The images she inscribes are all located within her life experience. Life as experienced by a woman. This relentless claiming of the space and the identity, and the uncompromising articulation of the woman's experience has all the characteristics of a political resistance within the constraints of a hegemonic patriarchal system. It is important to note that the passivity of the sleeping figure is deceptive, because the inner world that she has created is her own, constructed out of her own desires, and with this unambiguous expression she lays claim to the right to reinvent it.

The plate in the print is split into two. The lower strip which seems torn away from the top section depicts snap shots of material wealth. It alludes to the lure of wealth: its corrosions of the processes of thought that are involved in the perpetual negotiations we make within the world in which we live. Maybe it is the moral of the story. Or a warning sign that the inner world, whose freedom we cherish so much, is fragile and needs to be renegotiated constantly. The split between the two fragments in the intaglio is complete - both contained within their own space. The dominant space of the woman's world prevails over the insidious presence of the material wealth that seems to have crept in as an afterthought.

Can death be sleep,

when life is but a dream,

And scenes of bliss pass as a phantom by?

The transient pleasures as a vision seem,

And yet we think the greatest pain's to die…

from On Death by John Keats, 1814

The veil of darkness falls quietly over the sleeping woman like the inevitability of death whispering in the shadow of life. Only a small parting unveils a fragile luminous light. It spills out like the birth of life that dislocates the dominion of death. But the shroud of night is translucent and one can see that the ambient world continues in light as it does in darkness, as if life and death are part of the same reality in a seamless continuum.

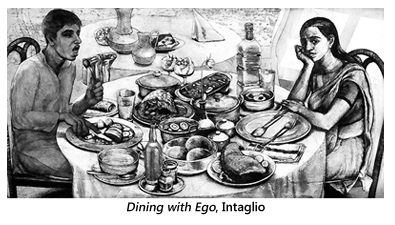

Relationships are the building blocks of our social rubic.  But relationships can also shatter into fragmented islands of lonely people staring at each other over a sea of indifference. They can be like two asteroids hurling across empty space on a collision course that is inevitable, unstoppable and will destroy them. This catastrophe might annihilate their world yet nobody will come to know of it and life will go on as if nothing has happened. Dining with Ego is such a world, with the seeds of its destruction embedded within. It is a usual day, like any other day we sit down for dinner. The spread is sumptuous. The menu varied. It is a sea of food. The man's plate is overflowing with the fare and he has already started gorging his mouth with it, totally engrossed in his animal deglutition. She is far away. Her plate is empty. She has totally forgotten to serve herself. Unnoticed at the far end of the frame she is drowning in her grief. The table is large like a chasm, whose continuously expanding fissure pushes the two protagonists into the fringes of the framework and almost out of it. The visual plane is dominated by the oversized table laden with oversized food: fish, chicken, eggs, soup; it is an unending procession of food. A delicate vase with a rose sits in the centre of it all, its head bent, reflecting the grief of the woman, almost out of place in the setting. The proportions of the utensils with the food on them have been rendered visibly larger than the humans at the table in a way that drives home the vulgar gluttony that has displaced the fragile bonds of relationships. More than just a surreal occurrence, the larger than life proportions take on an aberrant form, as if the voracity is not merely a hunger for food but an inexorable desire to consume everything within its periphery. This grotesque craving goes beyond food and possesses the ability to consume life, desires and being itself. Food, a symbol of the human need for sustenance and also the primal drive for self preservation, is transformed into a metaphor for the destructive rapacity of human relationships.

But relationships can also shatter into fragmented islands of lonely people staring at each other over a sea of indifference. They can be like two asteroids hurling across empty space on a collision course that is inevitable, unstoppable and will destroy them. This catastrophe might annihilate their world yet nobody will come to know of it and life will go on as if nothing has happened. Dining with Ego is such a world, with the seeds of its destruction embedded within. It is a usual day, like any other day we sit down for dinner. The spread is sumptuous. The menu varied. It is a sea of food. The man's plate is overflowing with the fare and he has already started gorging his mouth with it, totally engrossed in his animal deglutition. She is far away. Her plate is empty. She has totally forgotten to serve herself. Unnoticed at the far end of the frame she is drowning in her grief. The table is large like a chasm, whose continuously expanding fissure pushes the two protagonists into the fringes of the framework and almost out of it. The visual plane is dominated by the oversized table laden with oversized food: fish, chicken, eggs, soup; it is an unending procession of food. A delicate vase with a rose sits in the centre of it all, its head bent, reflecting the grief of the woman, almost out of place in the setting. The proportions of the utensils with the food on them have been rendered visibly larger than the humans at the table in a way that drives home the vulgar gluttony that has displaced the fragile bonds of relationships. More than just a surreal occurrence, the larger than life proportions take on an aberrant form, as if the voracity is not merely a hunger for food but an inexorable desire to consume everything within its periphery. This grotesque craving goes beyond food and possesses the ability to consume life, desires and being itself. Food, a symbol of the human need for sustenance and also the primal drive for self preservation, is transformed into a metaphor for the destructive rapacity of human relationships.

But the essence of the composition is not about devouring or craving, it is about grief. The table laden with food spreads out like an insurmountable abyss between these two. At one end is the man totally engrossed in his act of ingurgitation, oblivious to the world. He seems content with his loaded plate at one side of this enormous rift and totally unmindful and self absorbed. At the other end is the woman. Her plate is empty. She projects a strong apathy towards corporeal needs, her physical desires subjugated by the extent of her grief as she drowns in its dark depths. She seems to be looking out, gazing directly into the eyes of the spectator and implicating him/ her in her lament. Her grief is the inner grief.  It is not an external grief that is spectacular in nature, like those emerging from the catastrophes of the atomic holocausts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the devastating massacres of Rwanda and Burundi, or the horrors of Darfur. The melancholic gaze of the woman fixates the spectator only for a while, and then it wavers and travels beyond to an unknown destination. We realize that her grief is not a particular grief to a given reality. It is a meandering grief that has floated up and spilled over into this world from the depths of her inner self. This is not a grief accompanied by a tumultuous lament. Rather it is surrounded by silence. It is a tsunami of deafening silence that crashes over the landscape of time, collecting the debris of other shattered lives, dredging up years of deposited grief and opening fresh wounds. This woman's lament is not the grief of an individual, but the suffering of women across the ages.

It is not an external grief that is spectacular in nature, like those emerging from the catastrophes of the atomic holocausts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the devastating massacres of Rwanda and Burundi, or the horrors of Darfur. The melancholic gaze of the woman fixates the spectator only for a while, and then it wavers and travels beyond to an unknown destination. We realize that her grief is not a particular grief to a given reality. It is a meandering grief that has floated up and spilled over into this world from the depths of her inner self. This is not a grief accompanied by a tumultuous lament. Rather it is surrounded by silence. It is a tsunami of deafening silence that crashes over the landscape of time, collecting the debris of other shattered lives, dredging up years of deposited grief and opening fresh wounds. This woman's lament is not the grief of an individual, but the suffering of women across the ages.

Is it possible to speak of the pain? Nothing emanates from the edge of silence where the grief sites itself. The table, so full of food gurgling with the promise of satisfying all earthly desires of this lifetime has become an unfathomable chasm that will continue to isolate her endlessly in time. Pain and grief are not definable objects that we can imagine rather they are non-objects. They have a meaninglessness that drives them to the precipice where they attain a condition of non-existence. The woman looks away from the food in loathing, refusing to acknowledge it. Julia Kristeva mentions food loathing as the most elementary and most archaic form of abjection. The body of the woman in grief, by rejecting the food, pushes herself to the border of living and into the condition of a corpse - where it spits itself out and thus becomes an empty vessel devoid of the world without any god (Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, An Essay on Abjection, 1982). Even though this absence of meaning is inundating her, her grief is not a submission; it is a resistance, attained by expelling meaning to the condition of being and a refusal to fetishize the objects of desire. This insurrection in the mode of grief opens up a path for this woman, situated in the periphery of the picture, to make a move towards the centre. Her position in grief is that of an exile and it brings her forth to question “Where am I?” thereby destabilizing the constructs of patriarchal powers that have banished her to the margins.

Within the complex relationships and intimacies of these quiet protagonists that inhabit Anupam's constructs there is a belief that the structure does not define the body as the body defines its parameters. Everyone operates within certain limitations and resistance is not to let those limitations define you. Instead you confront it in such a way that it allows you to create new possibilities of freedom and revolution. Most of us experience the loss of maternal love and the fading whisper of our father's words in the course of time. Rather than just burying ourselves into a state of mourning we transform this loss into a cornerstone for building new dreams that we weave for the future.

The zinc plate is only a metal until we put our hands on it. The lines that we etch on it become its blood vessels giving life. The acid biting into it is a destructive act that will breathe the possibility of an afterlife, and the ink is the life force that we push into the lines. It is said every repetition is a unique experience; that another can never be a repeated. For the printmaker every print he or she pulls is a distinctive impression left in the march of time.