- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Antique

by Shoma Bhattacharjee

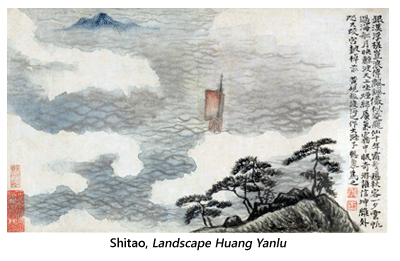

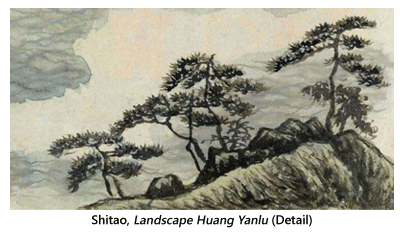

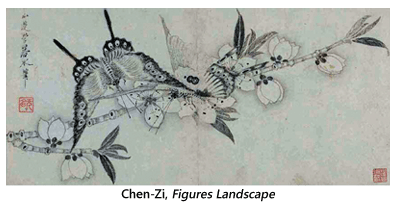

Whether the pen is mightier than the sword is debatable. Some may say going by events in contemporary Indiathat The Fast is turning out to be the mightier weapon. However, not even the most cynical would deny the sheer permanence of the pen. Or the brush in this case. The over 60 works of art now showing at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art go a long way in establishing that. The landscape paintings and calligraphies produced at the violent confluence of the Ming and Qing dynasties around the 17th century efficiently relay the ancient art of protest, to today's audience.

The show, entitled The Art of Dissent in 17th-Century China: Masterpieces of Ming Loyalist Art from the Chih Lo Lou Collection, will play till January 2, 2012. It has been curated by Maxwell K. Hearn, with Shi-yee Liu, both of the Metropolitan Museum's department of Asian art.  The works featured were collected in the 1950s and 1960s by late Hong Kong collector Ho Iu-kwong, who named his studio the Chih Lo Lou or Hall of Supreme Bliss.

The works featured were collected in the 1950s and 1960s by late Hong Kong collector Ho Iu-kwong, who named his studio the Chih Lo Lou or Hall of Supreme Bliss.

The reign of the Ming (1368-1644), meaning 'light,' signified a luminous time in Chinese history. It has been described by a historian as "one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history." However, in the last few decades of the dynasty, political weakness at the Ming court pushed large parts of the kingdom into chaotic darkness, ironically, showing the way to the Manchus. However, though the invaders stormed Beijing in 1644, they took a few more decades to stamp out the last of the armed Ming rebels in the south.

Meanwhile, the Ming loyalist 'leftover subjects,' or yimins, armed with just brush and ink, turned into artist-activists, non-violent resistors. “There's a long tradition of using art as a way of expressing one's feelings and response to a political situation," Hearn says. In tune with this timeless culture, the artists took psychological as well as physical refuge in nature, and their representations of landscape often projected their emotional responses to this radically changed world order. In transforming painting and calligraphy into vehicles for self-expression, they demonstrated a visionary departure from traditional styles and techniques. Some of the artists chose to disguise their identity and sought refuge in the landscape of their art, or withheld support to the Qings, as the Manchus christened themselves, by becoming Buddhist monks.

The inclusion of poetry in a landscape composition is, of course, a tradition of Chinese art. “The important thing in appreciating the works is to read both the poetry and the painting as conveying something of the individual's sentiments and response to the unfolding situation," Hearn points out. In this context, particularly noteworthy are the clusters of works by Huang Daozhou. In the forlorn Pines and Rock, Huang paints two ruined, entangled pine trees and part of a cliff, with the ironic inscription: “Even if I turned into rock, I wouldn't be obstinate.”  In reality, the prince-turned-monk Huang Daozhou was as obstinate as a rock when it came to asserting his allegiance to the fallen Ming.

In reality, the prince-turned-monk Huang Daozhou was as obstinate as a rock when it came to asserting his allegiance to the fallen Ming.

“It is not the content of the paintings but the style that's striking. These men were individualists who were interested in expressing themselves through their art, so as a very personal form of expression, they were not interested in representing the natural world, rather in using landscape as a vehicle for expressing their deepest feelings. By painting images of desolation in the natural world, they conveyed a sense of withdrawal of support from the Manchus,” the curator says.

Art writer Holland Cotter sheds further light: “Some, like Xiao Yuncong (1591-1669), devised subtle emblems of protest and mourning. His Ink Plum depicts a single plum tree, a symbol of ethical purity, as little more than a graceful but insubstantial twig. It floats unplanted in midair, as if it had been chopped off at the bottom or torn away from its roots.”

The exhibition has been organized into five sections on the basis of theme or region.

Ming martyrs: Post the 1644 invasion, for many doomed Ming officials and scholars it was a do or die battle. The first gallery highlights some of these morally-obstinate martyrs, notably Ni Yuanlu (1593-1644), who hanged himself, and Huang Daozhou (1585-1646), who died defending the old order. Their paintings and calligraphies reveal their noble characters through both the choice of subject and expressively daring styles.

Yellow Mountain and Nanjing regional schools: The most important centres of loyalist artistic activity were Nanjing and the rugged wilderness of Yellow Mountain. The two served as complementary poles in the urban-rural reality of Chinese life. Among the works on view from these regions are masterpieces by Zhang Feng (1628-1668), Kuncan (1612-1673) and Gong Xian (1619-1689) of the Nanjing school; and two iconic images by Hongren (1616-1663), the great Yellow Mountain patriarch.

Kuncan (1612-1673) and Gong Xian (1619-1689) of the Nanjing school; and two iconic images by Hongren (1616-1663), the great Yellow Mountain patriarch.

Guangdong artists: The Guangdong region in southwestern China has been represented by Kuang Lu (1604-1650) and Zhang Mu (1607-1687), among others. They either became martyrs or remained active participants in the resistance.

Monk painters: Two of the greatest artists of the early Qing period were Bada Shanren (1626-1705) and Shitao (1642-1707). Both were Ming princes who became Buddhist monks to escape persecution. Bada used abbreviated enigmatic imagery in both landscapes and flower-bird paintings, which spoke of a deeply troubled mental state. Shitao, a sophisticated theorist and a versatile artist, relied on direct observation of nature as well as his draftsmanship to create the most original landscape style of the 17th century.

Jiangsu and Zhejiang artists: The final section exhibits major works by masters working in the traditional artistic centres of Suzhou and Hangzhou. Among the Suzhou painters, Huang Xiangjian (1609-1673) is represented by an album that chronicles his perilous 1,400-mile journey in search of his old parents. Among the paintings by Zhejiang artists working near Hangzhou, a mammoth 12-panel set of landscapes of the four seasons by Lan Ying shows off his nonpareil painterly craft.

Also on display at the Met are porcelain ceramics, ivory figures and an array of the artists' implements like brushes, brush holders, ink stamps, even a desk.