- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

by Prof. Parag Roy

I was introduced to the name of Haren Das in my childhood when someone gave me a thin yellow-covered booklet entitled Bengal Village in Wood Engravings as a birthday gift. Below the title there was a picture of a boat and at the bottom the name of the artist, Haren Das. Even as a child I could appreciate the detailed black and white landscapes and almost photographic representations of rural Bengal. I tried to copy some of those landscapes with pen, brush and ink. The word “wood engraving” was written in the book but at the time I was too young to understand the meaning of the word. In our childhood the book was available in Kolkata's famous art material shop G.C.Laha. It was printed for the youngsters who loved to draw and paint, and with its help I started to admire the landscapes of Haren Das. Now, as a grownup man, I know that there were very few artists, who, throughout their career, remained busy in portraying the landscape of the rural Bengal. Haren's pictures create a window to see the easy and uncomplicated life of our familiar countryside. He had a way of coming close to his audience to depict the simple incidents he experienced in life. That simplicity in character and approach made him different from other artists of his period.

I started to admire the landscapes of Haren Das. Now, as a grownup man, I know that there were very few artists, who, throughout their career, remained busy in portraying the landscape of the rural Bengal. Haren's pictures create a window to see the easy and uncomplicated life of our familiar countryside. He had a way of coming close to his audience to depict the simple incidents he experienced in life. That simplicity in character and approach made him different from other artists of his period.

Das was born in 1921 and brought up in a small town named Dinajpore which is now located in Bangladesh. His family had property and a farmhouse in a village nearly three miles out of town. The beauty of the countryside of Bengal made a permanent impression upon him. From that small township the young fellow came to Kolkata to take admission in the Art College. Later he settled in Kolkata, started his career, and joined the Art College as a teacher, but could never forgot the simple values he inherited from the life of his native place.

The British administration settled industrial art schools in Lahore, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata, and they had appointed British artist-teachers and skilled technicians to train the native students. Their ambition was to produce skilled illustrators, calligraphers, draftsmen, block-makers and modellers to support the industries developed by European entrepreneurship in the newly formed colony. In the training schedule of the industrial schools subjects like drawing, still life studies, human figure studies, engraving, lithography and clay modelling were introduced. In those days European art historians and academicians didn't consider Indian art as a faculty of serious intellectual or cultural activity. But they appreciated the craftsmanship and technical skill of the native artisans. Thus these newly formed industrial schools delivered well-trained and technically competent artist-craftsmen to work as illustrators in industry. Calcutta School of Industrial Art was founded in 1854. After a few years, in 1865, the industrial school of Kolkata was named as the Government School of Art and Craft. In its history of more than one hundred and fifty years, the institution shifted its focus and played a pivotal role in development of modern Indian art practice. The Government Art Institution (presently The Government College of Art and Craft) carried the legacy of British academic schooling in its training program. Haren Das was one of the significant products of this college. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he remained loyal to the training he received from the academy. His training in printmaking came from his revered teacher, Ramendranath Chakraborty, and he remained devoted to his guidance throughout life.

the institution shifted its focus and played a pivotal role in development of modern Indian art practice. The Government Art Institution (presently The Government College of Art and Craft) carried the legacy of British academic schooling in its training program. Haren Das was one of the significant products of this college. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he remained loyal to the training he received from the academy. His training in printmaking came from his revered teacher, Ramendranath Chakraborty, and he remained devoted to his guidance throughout life.

To appreciate and analyze the art of Haren Das, one should have a clear conception about the separate characters of these two relief printmaking mediums known as woodcut and wood engraving. In the Printmakers Handbook authored by the famous printmaker Jane Stobart of Goldsmith College (UK), these differences are nicely explained: “Woodcuts are made from the side grain of wood known as the plank. Wood has a directional grain and there is not the same freedom of cutting as with lino. However, this resistance can result in more dynamic cuts, as you have to make a determined effort to make your image.” For wood engraving an artist needs the cross section of a piece of wood. Jane writes in her book: “wood engravings are made on the tight cross grain of timber such as box, pear, lemon and hornbeam woods, the most highly regarded and expensive being boxwood." A much more realistic image is possible in wood engraving. It helps an artist create minute details on the surface of the wood block. For these reasons, in the early age of printing technology, wood engraving was immensely popular among block-makers and graphic designers. After India's independence, boxwood (being an imported material) was not easily available to artists. During the 1950's and 60's, Haren Das might be the only Indian printmaker who actively engaged with the medium and tried to explore new possibilities with it.

Though subjects like lithography, engraving and wood engraving were part of the curriculum of Kolkata's Government Art School,  printmaking as a creative medium was not encouraged by the school in the pre-independence era. We find only a few serious attempts to explore printmaking in the second and third decades of 20th century: in places like Jorasanko Thakurbari and Kala Bhavan of Santiniketan. Actually in Jorasanko Thakurbari (the ancestral adobe of Rabindranath Tagore) an art commune named Vichitra Club (also known as Vichitra Sabha) was formed. Rabindranath urged the artists of Jorasanko to form such an organization and provided financial and moral support. Two of his renowned nephews, Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, with their disciples Nandalal Bose, Mukul Dey, Kashiram Debal and others joined the Vichitra Sabha as members. The artists of Vichitra Sabha were interested to experiment and explore new and unconventional mediums. The Japanese School of woodcut and lithography was in their area of interest. Also, the woodcuts and etchings by the German Expressionists artists impressed Rabindranath and he introduced these mediums to artists at Santiniketan.

printmaking as a creative medium was not encouraged by the school in the pre-independence era. We find only a few serious attempts to explore printmaking in the second and third decades of 20th century: in places like Jorasanko Thakurbari and Kala Bhavan of Santiniketan. Actually in Jorasanko Thakurbari (the ancestral adobe of Rabindranath Tagore) an art commune named Vichitra Club (also known as Vichitra Sabha) was formed. Rabindranath urged the artists of Jorasanko to form such an organization and provided financial and moral support. Two of his renowned nephews, Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, with their disciples Nandalal Bose, Mukul Dey, Kashiram Debal and others joined the Vichitra Sabha as members. The artists of Vichitra Sabha were interested to experiment and explore new and unconventional mediums. The Japanese School of woodcut and lithography was in their area of interest. Also, the woodcuts and etchings by the German Expressionists artists impressed Rabindranath and he introduced these mediums to artists at Santiniketan.

Haren Das, as a student, started his tutelage in Art College nearly twenty years after the closure of Vichitra Sabha. In the period from 1940 to 1960 modern Indian history passed through the most critical phases. The nationalist movement, independence, partition, communal riots, different types of political turmoil, and financial crisis kept society in a crucial position. This was not a comfortable situation for artists or creative people to practice. The financial condition of the society was not supportive to art activities. Printmakers were like a non-existent species. And it was in that situation that Haren Das devoted himself to the less popular medium  (among the modern artists) called wood engraving. Haren was brought up in a moderate background. He did not have any contact with elite or enlightened society, nor did he have any influential family. His only connection with Santiniketan was his teacher Ramendranath, who himself was an alumni of Kala Bhavan. Haren was proud of two of his college-mates, Muralidhar Tali and Safiuddin Ahmed. After partition in 1947, Safiuddin shifted his base to East Pakistan. In Bangladesh I once saw some old wood engravings of Safiuddin. I also remember some earlier wood engravings by Somnath Hore (who also graduated from Government Art School of Kolkata). All these works carried a strong flavour of British academic schooling.

(among the modern artists) called wood engraving. Haren was brought up in a moderate background. He did not have any contact with elite or enlightened society, nor did he have any influential family. His only connection with Santiniketan was his teacher Ramendranath, who himself was an alumni of Kala Bhavan. Haren was proud of two of his college-mates, Muralidhar Tali and Safiuddin Ahmed. After partition in 1947, Safiuddin shifted his base to East Pakistan. In Bangladesh I once saw some old wood engravings of Safiuddin. I also remember some earlier wood engravings by Somnath Hore (who also graduated from Government Art School of Kolkata). All these works carried a strong flavour of British academic schooling.

Renowned British engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) was considered the pioneer of the wood engraving technique, and in those days the Kolkata-based art schools were carrying the legacy of the Bewick-style of engraving. Artists at Santiniketan were inspired by Madame Karpeles and preferred to practice woodcut and linocut. In 1990, when I went to see Haren Das at his residence, he simply told me that in his student life he observed that the artists of Kala-Bhavan used more stylized images and their treatment of lines differed from the artists trained in the Government Art School. As an experienced artist, he observed the two parallel trends and appreciated both. He did not try to justify his acceptance (or lack of it) with complicated logic. Haren practiced wood engraving because he simply loved the medium.

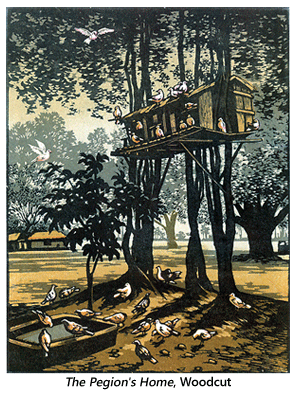

Haren Das can also be referred as one of the best exponents of the British school of wood engraving. Without any appreciation or support he kept devoted to the medium. His dedication to wood engraving made his name almost synonymous with the medium. In 1990 I visited his residence. That day, during conversation, he mentioned that he observed the techniques of colour woodcut prints by his teacher Ramendranath. According to Haren, Ramendranath used a Chinese technique with water-based colour. In that Chinese chromo-xylograph technique, colour stencil and brush were used. As he described, the technique also had lots of similarities with traditional Japanese woodcut. This inspired Haren to make multi-colour prints but he did not follow the oriental techniques of colour woodcut.  He experimented with the conventional medium that he had learnt in his institute. He kept loyal to the western technique that depends on oil-based printing ink and rubber rollers for the application of colours. He conceptualized the multi-block method that requires individual wood blocks for each and every colour. This is a common method used by the Japanease ukiyo-e printmakers, but Haren adopted the procedure and applied it through western technique. We must remember that Haren did not get any support from a specialized department. Multi-block wood engraving is a meticulous technique that requires lots of patience and perfection. Gradually, the devoted and dedicated artist achieved an incredible level of excellence. His colour engravings were treated with layers of colours. To make a Japanese ukiyo-e print, a team of artist-printmakers work together in a studio under the guidance of a master. But like most Indian printmakers, Haren himself did each and every step of the artworks, starting from layout to tracing, cutting and printing. Even after that, the perfection of his colour prints can easily be compared with any Japanese or western multicolour prints produced by the commercial studios.

He experimented with the conventional medium that he had learnt in his institute. He kept loyal to the western technique that depends on oil-based printing ink and rubber rollers for the application of colours. He conceptualized the multi-block method that requires individual wood blocks for each and every colour. This is a common method used by the Japanease ukiyo-e printmakers, but Haren adopted the procedure and applied it through western technique. We must remember that Haren did not get any support from a specialized department. Multi-block wood engraving is a meticulous technique that requires lots of patience and perfection. Gradually, the devoted and dedicated artist achieved an incredible level of excellence. His colour engravings were treated with layers of colours. To make a Japanese ukiyo-e print, a team of artist-printmakers work together in a studio under the guidance of a master. But like most Indian printmakers, Haren himself did each and every step of the artworks, starting from layout to tracing, cutting and printing. Even after that, the perfection of his colour prints can easily be compared with any Japanese or western multicolour prints produced by the commercial studios.

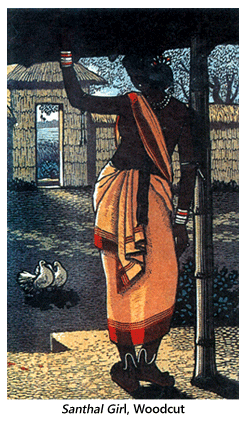

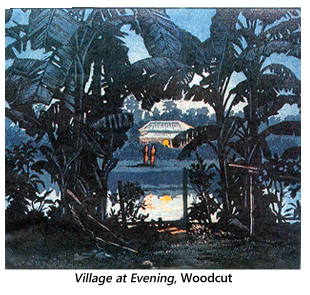

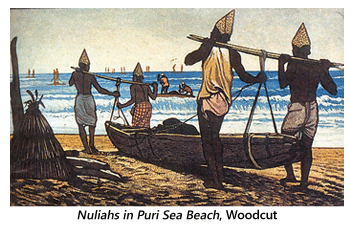

I would claim the work The Pigeon Home (Payrar Basha), created in 1956, as the best of all his works. The brilliant handling of the engraving tools to create details, clever and balanced use of the subtle nuances of green and delicate use of shadow and light made that print admirable. Another work entitled The Santhal Girl can be mentioned for its perceptive treatment of light and transparent shades of colour. I also fall into wonder when seeing the way he treated the seascape in the print titled as The Nuliahs in Puri Sea Beach (1962). The panoramic view of the sea, the treatment of the waves and usage of vignette in the shade of the sky make the work comparable with the prints of Japanese ukiyo-e master Hokusai.

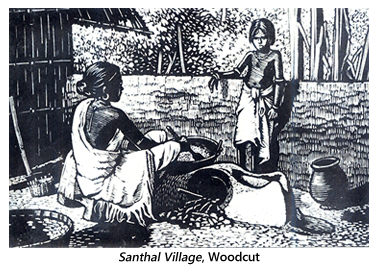

Haren also made a series of monochromic wood engravings. In these works he depicted rural Bengal through almost photographic viewpoints. A vivid descriptive narration of various locales was the most interesting and attractive area of his works. He used theatrical light, cast shadows, and the application of multi-point tinting tools to create different shades of tone. Das displayed a rare skill in executing separate treatments for the surfaces of wood, skin, glass, brick and other materials. Intelligent uses of chiaroscuro and detail representation make his works wonderful for the viewers' eye. Most of his famous works were initiated from outdoor studies and sketches. This close association with nature and his intimate observations of life make each of his works a personal statement.

To read his pictures one should follow his simple, honest and clear approach towards life. Haren Das kept himself isolated from the political turmoil, social crisis and discourses on the modern languages of art. In the interview with him that I took in 1990 he simply confessed that those were complicated things and he considered them as beyond his limitation of understanding.  According to Haren he could only execute things that he realized and experienced. For this indifferent attitude he has been criticized, but if we follow his works we can observe that he never shifted focus from narrating the nature and day-to-day life of the common people. Outdoor study and sketches were the main source of his inspiration. For new subjects he travelled to different parts of Bengal. In remote districts of the Chotonagpur plateaus and the simple life of the santhal villages Haren found his favourite spots.

According to Haren he could only execute things that he realized and experienced. For this indifferent attitude he has been criticized, but if we follow his works we can observe that he never shifted focus from narrating the nature and day-to-day life of the common people. Outdoor study and sketches were the main source of his inspiration. For new subjects he travelled to different parts of Bengal. In remote districts of the Chotonagpur plateaus and the simple life of the santhal villages Haren found his favourite spots.

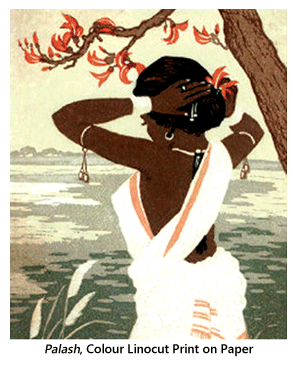

Das was determined not to accept oil painting or any other painterly method as his medium of work. He remained devoted to printmaking his entire life. Along with wood engraving, his craftsmanship in the mediums of lithography, etching, linocut and woodcut was also praiseworthy. Use of light, middle and dark tones in some of his aquatints proves his command of the technique. The distribution of white space in some of his linocuts reminds us of some of the landscapes created by Nandalal Bose to illustrate Sahaj Path.

Haren was sometimes puzzled about modern concepts of art. He also could not adopt the ideas and techniques of the Bengal School as advanced by Abanindranath and his pupils. There are a very few examples of Haren's experiments to make pictures with different stylistic approaches in etching, woodcut and lithograph. But other than his usual technical perfection, in those works Das could be found in a very confused state. These works were a sort of personal dialogue with his self. He never pretended that they were his mainstream of creation. Such confusions were very common among the Indian artists who were practicing at the middle phase of the last century. Haren kept observing of the changes happening in Indian art and had a deep respect for different research, style and concepts. But he knew his own limitations and nurtured the area of art he liked to deal with. Year after year he passionately worked with wood engraving without appreciation or acceptance. With time, the simple approach of his prints towards nature and life became accepted by collectors and art audiences. Most of the major galleries and art collections in India have his prints, and his prints have represented India at several international exhibitions, including those in Tokyo, Bulgaria, the USA, and Chile. After Haren's death in 1993 a few books have been published on him, but during his career his excellence as an artist was hardly recognized in the art world. His contribution as a pioneer of colour wood engraving, and his simple yet poetic capturing of rural Bengal, was never appreciated in his life time.