- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Future Calculus

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Concluding Essay

by Waswo X. Waswo

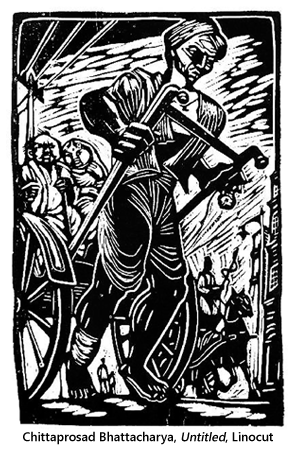

I was lucky enough to join the opening reception for the Chittaprosad Bhattacharya retrospective at Delhi Art Gallery a short time back. It was of course a gala affair, and an extremely well-attended exhibition. As a collector I picked up two more linocuts by this legendary Bengali artist, and as an artist I was simply overwhelmed with the genius and commitment of one of India's legendary printmakers:  a man who was keen to right social wrongs by coupling his talents for draughtsmanship, caricature and printmaking in a concerted effort to make political statement. It was here at this opening that I overheard a conversation between an older man and his wife. The woman, in an elegant and expensive sari, was pointing to a powerful linocut hanging just near me (it was a linocut I had actually considered to buy). "What about this one?" she asked her husband in a serious whisper. It was obvious the two were in shopping mode. "No, it looks too much like a print!" replied the husband. As they turned away, I felt my heart sinking.

a man who was keen to right social wrongs by coupling his talents for draughtsmanship, caricature and printmaking in a concerted effort to make political statement. It was here at this opening that I overheard a conversation between an older man and his wife. The woman, in an elegant and expensive sari, was pointing to a powerful linocut hanging just near me (it was a linocut I had actually considered to buy). "What about this one?" she asked her husband in a serious whisper. It was obvious the two were in shopping mode. "No, it looks too much like a print!" replied the husband. As they turned away, I felt my heart sinking.

If the lead essay in Part I of this series was somewhat academic in its approach, this concluding essay needs to be personal. The anecdote recounted above unfortunately represents an attitude and lack of knowledge all too prevalent among India's art collectors, galleries, and even, sadly to say, curators, writers and artists. The quick dismissal by this woman's husband of a fine example of Chittaprosad's best work, because it looked "too much like a print" (!), is hard for me to fathom. It was of course a print, and that was exactly its beauty. Arguably Chittaprosad's most important works were done through the medium of linocut. What this couple had passed by was a magnificent print depicting a family struggling through a flooded Bengali countryside. I had only failed to buy this piece myself because I was already woefully over budget. Fact is, I deeply coveted what this couple had dismissed through a lack of understanding. I imagined the older couple moving on to perhaps purchase one of Chittaprosad's drawings in pen and ink. I wanted to go talk to them. I wanted to ask them if they were aware that the linocut they had snubbed had started as a drawing, probably sketched directly onto linoleum, and then, through skill and sweat, that drawing had been patiently cut, line by line. I wanted to ask them if they were at all aware how much work the artist had put into the careful carving, inking, and pressing of this print. I wanted to ask if they were aware that the artist put a totality of work into this linocut that was certainly far greater than making a relatively quick drawing in pen and ink.

It was suggested many times while editing this trilogy that it would be desirable to print a glossary of printmaking terms. I resisted that idea and perhaps I was wrong to do so. Perhaps it was a type of print collector's snobbery, but I just could not understand the need. Do magazine's devoted to painting place glossaries explaining the terms "impasto", "chiaroscuro", "gouache" and "pastel"? There is a certain presumption of awareness that inheres to painting that does not adhere to printmaking. It is as if it is assumed that painting terms are well known, and if they are not they should be. A reader who does not know the meaning of terms such as "painting knife" or "palette" is expected to make their own effort to learn. Perhaps I have wrongly expected a similar awareness and/or ability to investigate printing techniques. (We have indeed included such a short glossary of printmaking terms in this issue. Yes, I have succumbed to pressure...but if this glossary helps anyone begin a learning process, I am happy for it.)

The truth is that modern-day printmaking has suffered from the ever-resilient assumption that people do not understand its methodology and are thus entitled to repeated explanations. Printmakers have thus become notoriously fond of bending over backwards to explain their techniques, and the unfortunate result is that the meanings and cultural worth of their images get lost in technical explanations of process, or justifications of the processes themselves. This over-eagerness to explain technique is visible in the way artists in India (both young and old) maintain the compulsive habit of marking their prints "woodcut", "drypoint", "lithograph", or "etching", most always on the lower edge of the image. Do artists who paint in oils mark their canvases "oil painting" in the lower left corner? Do photographers pen the word "photograph" at the bottom of their prints? Of course not. Painters and photographers hold an expectation that a certain level of sophistication will be brought by the viewing public. They assume such labelling on the image's supporting surface would not only be unnecessary, but distracting and ridiculous. The same expectation of a sophisticated viewing public ought to apply to the works of printmakers.

Through the course of these three issues that artetc. news & views has devoted to printmaking we have looked at its mediums both historically and in their present context. We have also sought to explore some of the ideas and concerns that the medium engenders.  Perhaps what has been missing has been a sense of the future, a sense of where printmaking in India might be headed in the years to come. If I were allowed a "wish list", some of what I would hope for would be the below.

Perhaps what has been missing has been a sense of the future, a sense of where printmaking in India might be headed in the years to come. If I were allowed a "wish list", some of what I would hope for would be the below.

I would wish that curators of thematic exhibitions consider the inclusion of prints when conceptualizing shows. Printmakers have been too long marginalized, kept in a segregated ghetto of "printmaking exhibitions" and excluded from serious curations that often include every kind of media except printmaking. I would wish for galleries to open themselves to the immense potential printmaking can have within a gallery's parameters. I would wish for educators to broaden the scope of printmaking pedagogy to include not only technique, but an inculcation of rigorous critical understanding of images themselves. I would wish for young printmakers to find innovative, fulfilling, and self-motivated means to continue their practice after graduation, and for older printmakers to aid them in that endeavour. I would wish for collectors to get over their obsession with one-of-a-kind "masterpieces" and embrace the joys of owning a segment of an edition. I would wish for the handmade prints of India's greatest artists to achieve the same global status as the prints of legendary European artists. I would wish for young printmakers to explore new thematic and visual territory through all the various print mediums, expanding printmaking's definitions and possibilities and pushing its boundaries beyond what is yet imagined. I would like to see a reawakening of the use of printed works as political activism, and a rediscovery of the dissemination of printed images by political artists in both rural and urban settings. I would like to see artists who not only continue the careful and meticulous methods of the masters, but actually improve upon their techniques. I would like to see artists unafraid to cross boundaries between printmaking and other mediums, without inhibitions or fears of deserting one medium for another. I would like to see print portfolios produced that are devoted to serious topics rather than nebulous themes, and well-written analytical essays included in such portfolios. I would like to see a realization that, depending upon the approach and integrity of the artist, a fine digital print can be just as complex and difficult to achieve as any other.

I have a lot more wishes. These are a few...but probably enough. It is up to today's young artists to show us what will actually be next.