- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Review

by Shoma Bhattacharjee

Moscow: Time: 1950s. Occasion: A TV reality show named What's My Line, where four players, blindfolded behind fancy masks, had to guess the identity of their illustrious guest. They could ask any number of questions to arrive at their conclusion. What was remarkable about this particular guest was that every  question directed at him evoked the same answer: “Si.”

question directed at him evoked the same answer: “Si.”

Are you a performer? Si

Are you a writer: Si

Do you often hog media space? Si

Are you a leading man? Si

And so on. Till the anchor had to intervene and tell the players that the guest was not a “leading man” in the conventional sense. To which, a player quipped that the man, invisible to her, seemed like a very “misleading man” indeed! The guest, a Salvador Dali Domenech, would likely have choreographed his eyes like a Kathakali dancer, and nodded “Si” to that as well! And he would not have been lying. Having excelled at the craft of multiplicity, Dali, a social cripple in his boyhood, reveled leading his audience on to make-believe mazes as he grew older.

Besides painting, printing, sculpting and installing, Dali made strange films and stranger jewellery, fashioned clothes, conceived and acted in advertisements, did his time as a Disney animator and set designer for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound, even created the spherical lollipop, as we know it today. Among other things, that is. Of course, it's impossible for any single show and a limited space to encapsulate these roles and worlds of the leading man from Catalonia. However, Salvador Dali: A Retrospective, currently on at Moscow's Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, tries its best. The exhibition is on till November 13. It has around 200 works, including 25 oil paintings, 20 watercolours, 70 drawings and graphic works, archival photographs and objects from the house of the late artist. Covering a broad time span (1920s-80s), the show focuses on the artist's late period. It condenses Dali's journey from a youth sifting different genres, germinating as a master Surrealist with a distinct 'paranoid-critical' language, and further as a 'mystical' experimenter who combined classical painting with optical illusions and nuclear science.

It has around 200 works, including 25 oil paintings, 20 watercolours, 70 drawings and graphic works, archival photographs and objects from the house of the late artist. Covering a broad time span (1920s-80s), the show focuses on the artist's late period. It condenses Dali's journey from a youth sifting different genres, germinating as a master Surrealist with a distinct 'paranoid-critical' language, and further as a 'mystical' experimenter who combined classical painting with optical illusions and nuclear science.

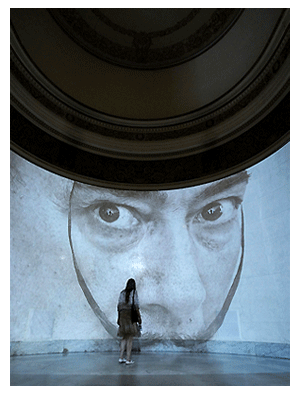

The show also has a first to its credit. Dali's paintings are being extensively shown in the Russian capital for the first time. Earlier, his graphics had been exhibited. Historically, the artist had been blacklisted by the politburo on both political and artistic grounds. “The work of Surrealists, including Dali, belonged to a zone of silence,” said Irina Antonova, director of the Pushkin Museum, describing Moscow's previous policy toward the artist, also known as a showman. She added that such themes were not popular in Russia until recent times, but now, many “blank spots” in literature and art and the cinema are being opened up for the people.

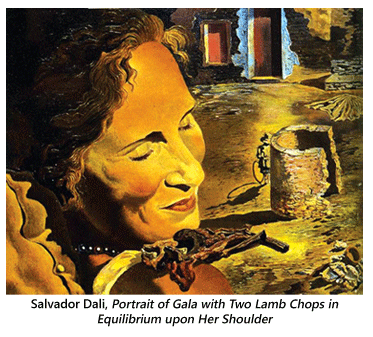

Dali's wife Gala unwittingly serves as the local link in this exposition. Born as Elena Diakonova, in the Russian city of Kazan,  Gala worked as a schoolteacher in her native land before emigrating and slipping into her global role of muse to many greats, including Dali and Max Ernst. His acute Gala-fixation is well expressed in many of his paintings, and some of his uncontrolled prose:

Gala worked as a schoolteacher in her native land before emigrating and slipping into her global role of muse to many greats, including Dali and Max Ernst. His acute Gala-fixation is well expressed in many of his paintings, and some of his uncontrolled prose:

I name my wife Gala, Galushka, Gradiva; Oliva, for the oval shape of her face and the colour of her skin; Oliveta, diminutive for Olive; and its delirious derivatives Oliueta, Oriueta, Buribeta, Buriueteta, Suliueta, Solibubuleta, Oliburibuleta, Ciueta, Liueta. I also call her Lionette, because when she gets angry she roars like the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion

Appropriately, her image dominates most of the major works on show here. Among the significant Gala-centric works at the Pushkin are Portrait of Gala with Two Lamb Chops in Equilibrium upon Her Shoulder (1934), Three Apparitions of the Visage of Gala (1945) and The Three Glorious Enigmas of Gala (1982). The lady with the endless capacity to inspire was married to artist Paul Eluard before meeting Dalí in 1929. They later married twice, in civil and Catholic ceremonies. Among the photographs displayed here, is one of their second wedding.

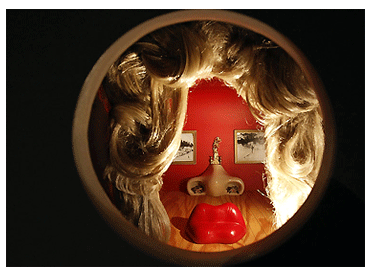

Muscovites will have to wait a little longer to see the original The Great Masturbator or The Persistence of Memory. However, they have not been denied masterpieces like Self-Portrait with Raphaelesque Neck (1921) Singularities (1935), Napoleon's Nose Transformed into a Pregnant Woman Strolling Her Shadow with Melancholic amongst Original Ruins (1945), Burning Giraffes and Telephones (1937), Dawn, Noon, Sunset, and Twilight (1979), The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1970) and Untitled: After Head of 'Giulio de Medici' Created by Miquelangelo (1981-82). The Mae West room has been recreated complete with lips-sofa and nostrils-fireplace.

The works have traveled from the Dali Theatre-Museum in Figueres, near Barcelona. Run by the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, the Figueres museum itself is a work of surreal art designed by the artist. Concrete bread rolls stud the external walls, spoofing its fortress-like pomposity. Giant white eggs line the terrace. The interiors are similarly Dalinian, and an attempt has been made to recreate this crazed dark red-and-black atmosphere at the Pushkin Museum by Bolshoi Theatre's celebrated scene painter, Boris Messerer. He has used strategic lighting to dramatize translucent eggs, trapezoid designs and white gowns, evoking sheer Salvador.

The interiors are similarly Dalinian, and an attempt has been made to recreate this crazed dark red-and-black atmosphere at the Pushkin Museum by Bolshoi Theatre's celebrated scene painter, Boris Messerer. He has used strategic lighting to dramatize translucent eggs, trapezoid designs and white gowns, evoking sheer Salvador.

Among the illustrations on view is a series made to accompany The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. The many photographs chronicle Dali's racy relationship with poet Federico Garcia Lorca and his Hollywood period, including shots with Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman, and Dali painting on film sets. Escaping the war in Europe, Dalí and Gala spent much of the 1940s on the USA rollercoaster, commanding attention wherever they went.

Predictably, whether in his lifetime or beyond, the Dali phenomenon has drawn diverse feedback from people who know what they are talking about. Jeff Koons credited Dali for his own decision to become a full-time artist, for “broadening the horizons forever.” On the other hand, George Orwell's famous comment, that in order to understand Dali's Surrealist paintings one had to appreciate that he was “a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being,” will forever echo across the antechambers of history, and often be taken out of context. But, as the Moscow show proves, whatever the response, it is always there in full forcesublime or ludicrous. As someone tweeted after the show: “Dali didn't die, he became John Galliano!”