- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Market Monitor

by Art Bug

Over the last two months, we have been dealing with the prospects of the printmaking market. In this last edition on the subject, let us look at how even the print market is divided, so much so, that it is at times threatening to artists themselves.

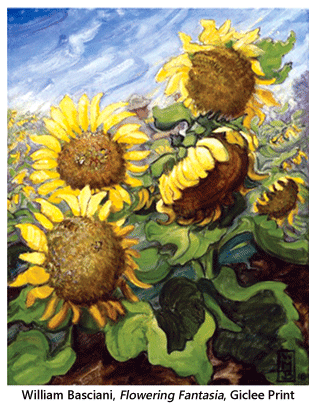

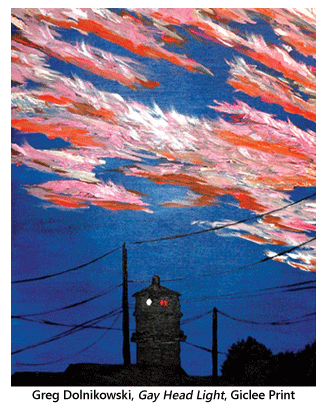

Internationally, there are counter market forces in motion. While on the one hand, there are artists who still practice the time-honoured methods of prints like etching, lithograph etc, a new breed of artists are now increasingly turning to digital art which by definition is either wholly or partially done with the help of computers and the reproduction of which, in most cases is digital.  The counter force, which threatens them are actually sleek galleries who are making and selling giclée prints of works, which are not originally digitally mastered.

The counter force, which threatens them are actually sleek galleries who are making and selling giclée prints of works, which are not originally digitally mastered.

This trend has been increasing since the low years of 2008-2009, when investments in fine art was at an ebb and thus, for buyers, as well as investors, giclée prints became a cheaper, if not necessarily a suitable alternative to buying artworks. What the investors failed to realise is that they were getting a raw deal, in trusting these glitzy, but in sheer artistic terms 'dubious' shopfloor and online galleries who were actually duping them into spending more for these digital prints of artworks in other-media. It was, as the trend shows, too late when some of the investors discovered that they were unable to sell their prints in the secondary market at even the cost of buying even after the market recovered.

Artbusiness.com recently came up with a scathing editorial on this practice.

“The commercialization of the art business by big business is nowhere more evident than in the marketing of reproduction prints, particularly giclees (computer prints of digital files) by entities billing themselves as fine art publishing companies. These reproductions are typically advertised as signed limited edition "fine art" prints and can sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars. The great majority, however, are nothing more than computer printouts of scans or photographs of paintings, watercolours, or works of art in other mediums (as opposed to digital works of art created by digital artists entirely or in part on computers which ARE considered to be originals). Repro print artists usually have nothing to do with producing these editions, their only participation being signing their names which takes maybe thirty seconds or so per print at most. And that's supposed to be worth hundreds or thousands of dollars? No way. But the people hawking these reproductions sure want you to think so and sure manage to talk plenty of people (into) believing it.

Barney Davey, the art market wizard who has been intimately involved in the art business since 1988, has written quite a few books on art business and has been a sales and marketing executive for Decor magazine and its sister Decor Expo tradeshows, writes in his blog: “In the art business, there is a bifurcation in the print market. That is, there are those fine art prints made in time-honoured fashion which, by the nature of their creation, are limited. These would include etchings, woodcuts, aquatints, engravings, serigraphs, stone lithographs and so forth.

there is a bifurcation in the print market. That is, there are those fine art prints made in time-honoured fashion which, by the nature of their creation, are limited. These would include etchings, woodcuts, aquatints, engravings, serigraphs, stone lithographs and so forth.

The other component of the print market primarily is made up of reproductions of original art. Some would call this the decorative art market, while others reserve that term for the open edition and poster market. How you describe it has as much to do with what end of the market you derive your income as anything.

If you are an artist, dealer or collector involved with etchings, your view of a giclée is likely to be a decorative reproduction. On the other hand, if you make your living selling giclees, or some other form or fine art reproductions, you may take issue with your work being called decorative art. Unfortunately, you can only control how you market your work.”

Barney also makes it clear as how to go about it. “My estimation is it will be very difficult for the market to bring us back to the old days of a booming profitable secondary art market for several reasons. First, most artists working in multiple these days are using the giclée or digital printing format. I do not believe the public clamours for limited edition giclées. I think it would rather pay a little less and get to enjoy the art. This notion is supported by evidence some longtime publishers in the giclée market are moving away from creating limited editions in this market. Lastly, once there is a widespread established pattern of digital prints not increasing in value, it will be very difficult to reverse such a trend.

“This may be a market with a beautiful creative product, but it also (is) a business that follows trends. If the trend grows stronger to open editions, it will depress the secondary market for fine art print reproductions. That is not all bad. I think it will force the art to be sold for its enjoyment rather than the implied notion it will increase in value. Buyers of giclees found before the current economic crunch they could not recover close to the sale price of prints they bought when they tried to take them back to galleries, sell them on eBay, or through an art broker. Things surely have not improved in recent years.”

So how should an artist thinking about getting into the print market proceed?

Barney says, “I think giclees are a wonderful medium to help sell more work. Rather than looking to maximize the sale of a limited edition, I suggest keeping the edition open. There is no reason the pieces cannot still be numbered using your own open numbering convention. If the artist's work does become collectible, then the lower numbers will likely have some higher than retail secondary market value.

For those who feel a need for limited editions, I would consider producing a small edition of 200 or less that is hand-embellished by the artist. I believe if it is clearly stated the edition will be accompanied by lower-priced open edition pieces, there would not be conflict with buyers.” He gives the example of American artist Terry Redlin, who was able for decades to sell both open and limited editions of the same images without creating a problem for his self-publishing company or the dealers who carried his work.

I would consider producing a small edition of 200 or less that is hand-embellished by the artist. I believe if it is clearly stated the edition will be accompanied by lower-priced open edition pieces, there would not be conflict with buyers.” He gives the example of American artist Terry Redlin, who was able for decades to sell both open and limited editions of the same images without creating a problem for his self-publishing company or the dealers who carried his work.

There is another school of thought though. As the artbusiness.com editorial suggests, “In the meantime, commercial fine art print and giclee publishing companies roll on. They flood the marketplace with slick websites, big advertising campaigns, beautifully appointed galleries in major tourist destinations, slick trained sales people, and ever more mutating terminologies and confusing explanations of what it is that they actually sell. All the while, they strengthen their foothold and effectively stymie a significant percentage of the art buying public.

If you're an artist-- ESPECIALLY a digital artist-- you might well consider getting involved and informed on this issue, and learn how to explain the difference between your originals (including original digital works of art) and signed limited edition giclee reproduction computer prints of works of art in other mediums produced by commercial publishing companies. Galleries that sell original art might get proactive on this matter as well and make concerted efforts to educate their clienteles about how to distinguish between original works of art and reproductions or copies of original works of art. On the legal side, lawyers for the arts should seriously consider lobbying for better disclosure laws. Criteria for labelling and describing reproduction limited edition copy prints should be standardized, made easy to understand, and be required reading for potential buyers– BEFORE they buy their "art," not after.”

We hope, all that will perhaps give one a clear view of how to fight the counter forces in the printmaking arena.