- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Conversations with Woodcut

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

The prints of Prathap Modi

by Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi

In the ever changing techno-cultural landscape of our contemporary times, where the very processing of the artistic image has witnessed a significant change, it is interesting to think of this effect on more conventional mediums like printmaking. Printmaking mediums have been in constant transition throughout history, very often questioning the conventional tags attached to them. Some Indian contemporary artists, who work primarily as printmakers, have conceptualized new and interesting possibilities that surpass the established assumptions about printmaking as a medium. Within this context it is interesting to consider Baroda-based Prathap Modi as artist/printmaker. His self-conscious intervention into the possibilities of printmaking,  and woodcut in particular, is a fascinating inquiry in the field of contemporary art.

and woodcut in particular, is a fascinating inquiry in the field of contemporary art.

In understanding the ways in which Prathap has pushed the limits of the woodcut it is necessary for us to look back briefly into the history of the medium itself. In its early development woodcut was a carved wooden block stamped to create impressions on clay and wax surfaces. Originating in Egypt and China for the purpose of making decorative and symbolic motifs, woodcut advanced into a matured stage with the advent of paper in China during the 2nd century A.D. The images that were produced in China, and at a later juncture in Japan, were illustrations of religious subjects. This tradition got consolidated with the invention of movable type in Europe, where woodcuts developed as an accompanying and highly sophisticated form of illustration for religious books.

The use of woodcut as an unique artistic medium achieved prominence only during the late 15th century, especially with the eminent interventions of Albrecht Durer and Hans Holbein in Germany. Much later in time many modern masters such as Edgar Degas and Paul Gauguin were influenced by the visual rendering of Japanese woodcuts. The period of German Expressionism also saw a brief revival of woodcut, as the artists of this time were inspired by the aesthetic vitality of medieval woodcuts from Germany. In the Indian context, early pioneers of woodcut and engraving belonged to the Bengal school. Binode Behari Mukherjee and Nandalal Bose for instance worked with the medium in varying degrees, while others such as Haren Das worked with the medium almost exclusively. During the 1930's and 40's artists such as Chittaprosad Bhattacharya revived woodcut as a means of popular social communication.  Chittaprosad was seminal in the illustrated documentation of famine-affected Bengal through very expressionistic woodcuts and linocuts in a sombre black and white.

Chittaprosad was seminal in the illustrated documentation of famine-affected Bengal through very expressionistic woodcuts and linocuts in a sombre black and white.

The institutionalization of printmaking as an artistic medium in Indian art schools during the post-independent era gave further rise to the proliferation of woodcut as a medium. Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan and the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda, have been seminal institutions that paved a revival of graphic arts within the Indian art scene. In the recent past some young printmakers from these institutions have invented a new scale and process that pushes many established conventions of printmaking. Prathap Modi comes from this generation of artists who have made significant attempts to redefine the very role of printmaking in general, and woodcut in particular.

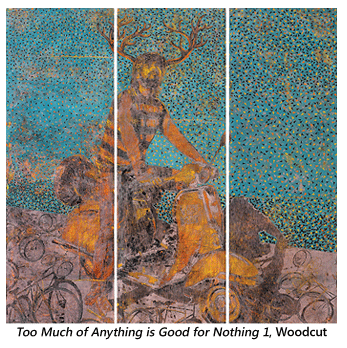

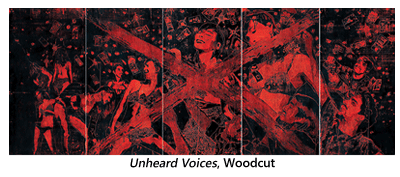

Coming from a small town near Vishakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh, Prathap Modi's ground for artistic interest was made during his training under the methodical mentor T. Sudhakar Reddy at the Department of Printmaking, School of Fine Arts, Andhra University. His post-graduate studies at the Department of Graphic Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda, helped him to structure his practice further and conceptualize a contemporary artistic language. As an independent art practitioner today, Prathap predominantly works with printmaking and most often with the medium of woodcut. In many significant ways he has managed to extend its limits. One such instance is that of large-scale woodcut, which is historically understood to be limited in the matter of its scale of execution. Speaking about this limitation with the medium Modi says, “I always wanted to move beyond the existing rules of the game, this has been my passion and motivation ever since I began producing art.” Prathap's striving for redefining conventions led him to produce gigantic woodcut prints that run into many feet, some even having the size of mural paintings. The peculiarity of the processes he uses to achieve this scale is worth consideration. Modi takes a large image composition and splits it into multiple wooden panels which are carved and printed on papers separately, but using the same colour scheme. Multicolour printing in this case is done with the spooning method.  These individually printed panels are later assembled and framed into a total composition. While the aspect of scale is what one immediately notices about Modi's works, one also notices the extremely careful crafting of minute details, with patterns creating visual segregations on the foreground and background of the images. The subtleness of the colour combinations are also unique to his work, and help to assure the efficiency of powerful images.

These individually printed panels are later assembled and framed into a total composition. While the aspect of scale is what one immediately notices about Modi's works, one also notices the extremely careful crafting of minute details, with patterns creating visual segregations on the foreground and background of the images. The subtleness of the colour combinations are also unique to his work, and help to assure the efficiency of powerful images.

In conceptually conversing with the woodcut works of Prathap Modi, a series of visual relationships are established between the representations of human figures, animals and other material objects. In speaking of the larger motivation behind his work Prathap notes, “As an artist, through my work, I try to communicate to my contemporaries what I personally think and feel of the changing realities around us.” In other words, his works have a straight forward visual appeal reflecting, reacting, and conversing with contemporary social realities. While desire and fantasy become the key conceptual undertones appearing and reappearing in many contexts, the well-crafted pictorial compositions often show the artist's self image as the key catalyst. These works place Prathap in a long lineage of artists who image themselves within their work. But it is necessary to see the diversity with which the artistic self is rendered in his context.

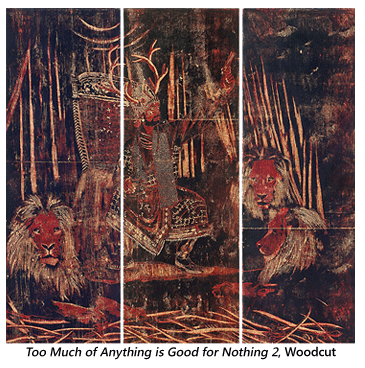

In the case of Prathap the artistic self image stands as a conversing agent between the past and the present, or taking it further conceptually, between tradition and modernity. For example, in the recent series of woodcut prints titled Too Much of Anything is Good for Nothing, there is a revival from the past of instances that are almost blurred from our everyday lives. But on the other hand the work is a self conscious critique of the present and its effects on the cultural landscape. This visual collage of past and present configured in a new conceptual frame creates play acts of fantasy. The king figure surrounded by lions in a royal courtly setup holds a gun in his hand. The man in police dress, with a divine halo, is represented in the iconography of the multi-limbed Hindu god, standing on weapons spread on the floor.  In a sense, these contradictions and dichotomies foreground a new symbolic relationship between objects/elements/images referenced from different timeframes of cultural history.

In a sense, these contradictions and dichotomies foreground a new symbolic relationship between objects/elements/images referenced from different timeframes of cultural history.

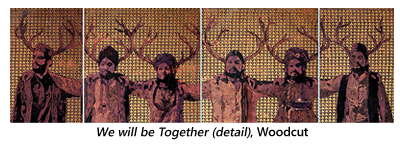

In another work titled We will be together, Prathap deals with the question of identity formation. By addressing the tension that has been built up in the recent past around regional, religious and ethnic identities, he strives for a world that can surpass all these barriers. In the words of the artist, “This work looks for a utopian world that is beyond caste, sex and religion; one that takes up humanity as the fundamental mode of dealing with the world.” While all the figures in this work stand in different traditional attires, the gesture of laying hands on each other's shoulders is a suggestion towards the imagined world of togetherness he proposes. By adopting an artistic process that multiplies the same image into many, the diversities are translated into different attires and inscribed onto the self image of the artist. The colour scheme through which the layers are rendered adds on, blending the position of each figure next to the other and adhering to a harmony of the total compositional frame.

As a recent development in his work the carved wood blocks that are the leftover residue of the prints are later processed and put together in sculptural frames as works in their own right. This in certain ways stands as a processed afterlife of the work, marking both (the prints and the woods processed) as active sites of signification. With such inventive modes of artistic practice and process Prathap blurs the boundaries between the conventionally established artistic mediums. In short, by attempting to surpass the existing conventions of artistic practice in general, and printmaking in particular, Prathap conceptualizes a new terrain, one that slides across multiple artistic mediums and processes with an eased sophistication.