- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

A Rich Theater of Visuality

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

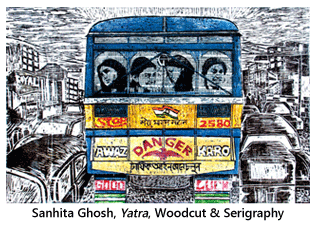

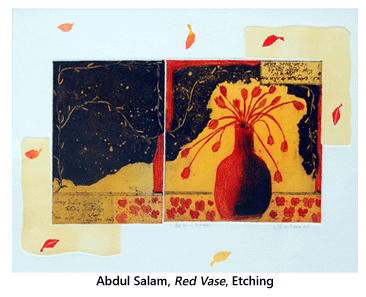

The works of Sanhita Ghosh and Abdul Salam

by Nanak Ganguly

Printmaking does not allow many corrections to be made as compared to painting or sculpture. One needs to be more definite in ones work, and that itself is one of the greatest qualities of the medium. You need to pre-plan. Printmaking demands that you be profound in the process.

As we are condemned to freedom and meaning we are condemned for transgression. Only by destroying ourselves, only in death, can we rid ourselves of satisfaction and steep ourselves in the free accidental play of desire, but to do so is to reiterate the death of God and death of the God-simulacrum, the subject. The subject that knows, idealizes and acts pragmatically is lacerated. Subject and self are no longer stable sources of meaning and productivity, but in these printmakers become accidents and nomads. Only in the dissolution of the subject do we know that consciousness is the ecstatic discovery of human destiny. Not an originator or proprietor, but a fissure, an opening where you would like to grasp your timeless substance and encounter only a slipping; only the coordinated play of your perishable elements. To be profound, the printmaker needs to be meditative. The process of acquiring mastery over the technique will lead one to a meditative mode and once this is achieved it helps to be very profound.

Knowledge of materials, methods and techniques are the essentials. Technique is not art, but these are inseparable in a successful work. Our acrobatics make knowledge and utility a surrendering of language where the air to each thing gives an exact place, a name rhythm, but only for the moment, because myriad possibilities exist to recall.

There is an entire process through which printmakers tear up conventions and ways of seeing and saying. The real importance of present art practice is not only to challenge representation as a 'formidable tool of domination' but to contribute to a redefinition of realism, abstraction and cultural representation.  One of the important problems facing non-centrist (non-western) international culture in all parts of the world is the need to come to terms with essentialist thinking in order to create new concepts of true open-ended fields of cultural construction. Printmaking is a distinctive language in comparison to painting and sculpture in terms of its technical orientation and the distinctive character of a print. The sheer pleasure of making a block for printing in any existing method is joyous and the excitement of the ultimate result can be again compared with blissful meditative engagement.

One of the important problems facing non-centrist (non-western) international culture in all parts of the world is the need to come to terms with essentialist thinking in order to create new concepts of true open-ended fields of cultural construction. Printmaking is a distinctive language in comparison to painting and sculpture in terms of its technical orientation and the distinctive character of a print. The sheer pleasure of making a block for printing in any existing method is joyous and the excitement of the ultimate result can be again compared with blissful meditative engagement.

Printmaking is a process that expands the visual vocabulary while an artist evolves. The technical expertise is equally important: to express visual concerns where both the technique and interpretation of the subject hold together during the process of any work. There is the purity of a single medium giving birth to an immense pleasure, as the printmaker enjoys the sensitivity of each visual aspect. These tear up the spectator, who finds his/herself torn between received ideas/feelings that are dismembered by each printmaker's plate. “A visual text that is seized with desire, mirth, resemblance, vaginates, laughs, covers, itself with spots, different sexes and century effects, and unfolds itself, neither the one nor the other, nor oneself, but crossed over, running, extraordinary, natural, neither Achilles nor Amazon, nor Hamlet father or Hamlet, but the child of all: his mother is unlimited, and he rejoices” (-Helene Cixous).

Two printmakers are discussed here whose art reaches out to us with a world of infinitely rich theatre, weaving and re-weaving a potent spell for all of who dare to share in the drama. Sanhita Ghosh experiments with parity of form and dialogue between markers in juxtaposition, producing a subliminal text in her serigraphy. The existential meets the topical and the present moments are fleeting. Linear scrawls and sweep of the lines evoke painterly traditions; her act of printmaking makes multiple entries and exits to leaf through the surface. Her etchings are travels of a pensive mind that adheres to a humble submission of space and its infinite possibilities rather than to specificities of form and their impositions. Sanhita meditates upon the pictorial surface to arrive at a response that lends a sort of primordial energy to her work. A world of “kitchen sink” paraphernalia substitutes the external one, translating feeling and emotions into a visual language. It is evident in the way she uses light and keeps the source a revelation. It becomes apparent viewing her work that Sanhita enjoys solitude. Her works awaken and take shape in silence, a texture she gifts them with fluent strokes that allow these pulsating gestures to follow natural folds. She uses them as solid fields of motion, contradicting nature and this distinct use of lines create a formal contradiction on the stone/plate. It gives life to the figures, a contradiction that is further heightened by a gesture, a look or an attitude is an inclusive act, unassuming as it is realistic. And it is bound to give a direction as it is realistic, and it is bound to give a direction as many of her protagonists do, to a more sympathetic understanding.

It is evident in the way she uses light and keeps the source a revelation. It becomes apparent viewing her work that Sanhita enjoys solitude. Her works awaken and take shape in silence, a texture she gifts them with fluent strokes that allow these pulsating gestures to follow natural folds. She uses them as solid fields of motion, contradicting nature and this distinct use of lines create a formal contradiction on the stone/plate. It gives life to the figures, a contradiction that is further heightened by a gesture, a look or an attitude is an inclusive act, unassuming as it is realistic. And it is bound to give a direction as it is realistic, and it is bound to give a direction as many of her protagonists do, to a more sympathetic understanding.

There is intense activity, a narration, nuances; obviously the energy made visible is controlled, and one has to watch closely the expressive visual modulation of colours which are woven in interlocking planes and are so thin that they may go unnoticed. Her image is an act of her mind where the memory mode plays a vital part; the memory of surface values remains with us whether we are looking at her work or not. When the images are not before us the recall sensations stay with us; the interaction between repetition and recollection has already become a part of the memory. What stays in the memory is not so much the repetitive nature of the surface but the sensations one has had of it.

Sanhita studied at Rabindra Bharati, Kolkata. In her ongoing pursuits she mainly does etchings and lithographs. She wavers to and forth simultaneously from large to relatively small formats, working closer to the surface with a sense of intimacy in the small and a sense of distance and space in the large. She adds a sense of monumentality with markers used instinctively to stimulate the surface. Her acts follow an internal spontaneity and spirituality becomes a self-generating organism.

In Abdul Salam's Parade the subject that knows, idealizes, and acts pragmatically is lacerated. Subject and self are no longer stable sources of meaning and productivity but become accidental and nomadic. How does one sail across these still-lifes, the sparse and unobtrusive grounds where all leads are buried? Along with the modernist techniques Abdul foregrounds other devices to celebrate the surface, illuminating, and inexorably bringing to life a surface he fears might dull.  The visual parable is construed on an imaginary triangle whose matrices are represented by the audience, the artist and those individuals who serve as the protagonists of his prints. Similar to East European writer's wisdom, as in Bohumil Hrabal's journey on the boundaryless maps in The Closely Watched Trains, he works with two important kinds of visuals: the static and the mobile. Salam situates his subjects in a way that capture these points of coincidence through shrewd editing, through aperture, through the choice of detail and through the deployment of chosen objects in space.

The visual parable is construed on an imaginary triangle whose matrices are represented by the audience, the artist and those individuals who serve as the protagonists of his prints. Similar to East European writer's wisdom, as in Bohumil Hrabal's journey on the boundaryless maps in The Closely Watched Trains, he works with two important kinds of visuals: the static and the mobile. Salam situates his subjects in a way that capture these points of coincidence through shrewd editing, through aperture, through the choice of detail and through the deployment of chosen objects in space.

Our acrobatics make knowledge and utility a surrendering of language. 'Acts' are despicable for they stifle passions and subjugate them to servility. But here wondrous shifts between intellectual processes and explicit physical activities reunite the life of the mind with its bodily ground, disavowing the printmaker's imbrications within the collective nightmare of modernity. Salam uncovers the terrible beauty and truth of our first-person plural condition. These remain chanced encounters for us; the dignity that once existed within the interface is now scattered across the silence of these forms. The printmaker writes the poetry of a lavish daytime and the record of an inexhaustible timeless world. The intricate illusionist lines in the background of his works are an expression of an energy which we are surrounded with and through which phenomena can opens up to a layered space. So the whole process of his work represents a physical engagement with the technical aspect and the psychological meditative aspect which elevates and eventually gives a catharsis and purification for the soul.

In Abdul Salam's etchings Broken Vase or Red Vase the compositions assume an act where desire, useless and excessive is the practice of freedom and transgression, is associated with living, living to the point of destiny, interacting with a world that ends, a world that is always ending. This is not despair, but a shrewd mind behind an honest eye that in wry observation creates small poems in a book of knowledge. Abdul shows there is no wisdom unsharpened by wounding wit; that motion is an essential motion, and these are essential poems.