- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Review

by Sritama Halder

Kolkata: A retrospective exhibition of works by the artist Chittaprosad, organized by the Delhi Art Gallery (DAG), was held at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata, from August 31 to September 11. The exhibits currently constitute the collection of this private gallery. A number of books on or by Chittaprosad have been published by DAG to coincide with this occasion. Among them probably the most significant is the artist's sketch book titled Hungry Bengal. This book, a first-hand documentation both in texts and visuals during the artist's travel around the famine devastated Bengal was banned by the colonial British authority immediately after its publication and most of the copies were destroyed. DAG has reprinted it from what is probably the sole surviving copy) that remained with Chittaprosad's family. The other books which constitute the five volume package include a facsimile edition of a sketch book of portraits of political personalities by the artist, a collection of select letters translated into English and a two-volume monograph documenting and analyzing the life and works of Chittaprosad.

As an artist, Chittaprosad had been largely forgotten and less explored. A few scholarly papers, a fragmentary space in the Art History syllabus in the art colleges and some stray references when discussing about the art of India in the 40s constitute the only visibility of the artist. The last time Kolkata saw some of his works was in the form of a consolidated exhibition 1993.

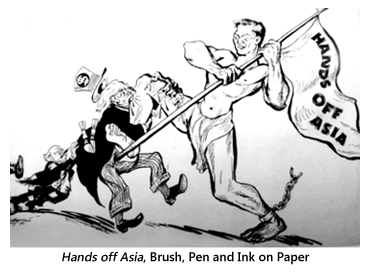

The sketches of the Hungry Bengal have a documentary value that fixes them within the brackets of a particular historical time. The same can be said about the 'propaganda' posters which were inspired by their Russian sources. These posters, too, are combinations of visuals and texts. The visuals often literally transcribe the text and vice versa. The statements written over the works not only form an integral part of the composition but they also spell out the events that triggered off the works. Events like the farmers' revolt or freedom for ordinary men remain for today's viewer the outcome of a particular socio-political condition and the sketches and posters are interpreted as the remembrance of a struggling past. If Chittaprosad's political works are disassociated from their historical context and interpreted as perpetual symbols then they may still be contextually relevant to contemporary situations.

The exhibition constituted of the artist's paintings, portrait studies and other compositions in pen and ink and lino-cut prints, posters, sketches, letters, toys, puppets and a replica of the kind of puppet theatre which was gifted to him by his Czechoslovakian admirers. Also running on a wall of the gallery was a film on the artist by the Czech director Pavel Hobl. The original copy of the Hungry Bengal, photographs of the artist and his family and associates, his party membership card, letters etc were also on display. What the exhibition did was reconstruct Chittaprosad as a multi-faceted personality and a multi-dimensional artist. This essay concentrates mainly on the works that are less exposed to the audience. More than following a strict chronological order only, the exhibits were rather grouped according theme and mediums.

A closer look to some of the exhibition displays would help us engage with the artist and his preoccupations better. The section which focused on chromatic paintings had works done in mediums ranging from oil on canvas and on masonite board, pastel on paper, pen and ink and water colour. The pictorial style varied considerably and indexed diversity in linguistic interest.

An untitled and undated work a group of four done in pastel on paper pasted on mount-board is treated differently. The colours are bright this time. Brown is only used for the hair and the hint of shadow on the faces and necks. The roundness of the human forms does not depend on the use of light and shade. It rather depends on the direction of the lines. Shadow here is used for creating a high contrast with yellow, blue and white. The pictorial space is also treated differently. The tangible, heavy space of the previous work is replaced by a fleeting and lighter one.  The faces are distorted through a kind of post-Cubist geometry; they are pensive and lack the serenity of the woman's face in the previous painting.

The faces are distorted through a kind of post-Cubist geometry; they are pensive and lack the serenity of the woman's face in the previous painting.

His still life studies with flowers and fruits such as Still Life (1950, oil on paper) and Blue Flowers (1952, oil on masonite board) tend to look like academic exercises while early nature studies such as Ganga (1939, water colour, pen and ink on paper) shows a child-like quality. Many of his works can be traced to their source inspirations in western art movements like Cubism, and Fauvism.

His paintings have an air of tentativeness. They show an artist's life long struggle in search of a language of his own during a time when Indian art was hesitating between the ossified Bengal School and the dominant tendency of experimentation through derived languages of western origin.

Stylistically Chittaprosad's illustrations for children's books include titled like the Kingdom of Rasogolla, the Frogs and the Elephants written and illustrated by the artist and the Ramayana which was left incomplete. These illustrations show a complete departure from his other works. The black and white and occasional colour lino-cut prints discard one fundamental characteristic of the works that concentrate on a social issue where the subjects stand against a stark blank space so that the viewer's attention concentrates only on the subject. For example, in the drawings of Hungry Bengal the blank place also reveals the sheer non-belongingness of the working class people.

In the illustrations, however, the empty space is almost always absent. The foreground is completely occupied with the forms. Figures of the characters are thickly set. With large eyes, short and round limbs they have a puppet-like appearance.

Chittaprosad, in the 1950s, did a series of works on folk dances of India. These works incorporated a lot of folk motifs and styles in terms of flowing lines and forms.These may also remind one of Nandalal's Haripura posters.

The reference of the shadow puppetry is not just an idle guess. Chittaprosad learnt puppetry from his Czech friend F. Salaba who presented him a puppet stage. He even started his own puppet theatre called Khelaghar for the kids from the nearby slums. He used to write the plays, design the stage-set and make the puppets himself, accompanied and aided by members of Khelaghar.

The exhibition was a wonderful effort to reintroduce Chittaprosad as an artist who not only worked from his sense of social responsibility and political commitment. He was an artist for whom art was something to be celebrated.