- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Sixteen printmakers talk about their work

- The Imprinted Body

- A Chai with Vijay Bagodi

- The Wood Engravings of Haren Das

- A Physical Perception of Matter

- Feminine Worlds

- A Rich Theater of Visuality

- A Medley of Tradition

- Decontextualizing Reality

- Printmaking and/as the New Media

- Conversations with Woodcut

- Persistence of Anomaly

- Sakti Burman - In Paris with Love

- Lalu Prasad Shaw: The Journey Man

- Future Calculus

- A Note on Prints, Reproductions and Editions

- A Basic Glossary of Print Media

- The Art of Dissent: Ming Loyalist Art

- Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Twelfth edition of Toronto International Art Fair

- Vintage Photographs of the Maharajas

- Göteborg International Biennial

- A Museum, a Retrospect & a Centenary for K.K. Hebbar:

- Recent and Retrospective: Showcase of Shuvaprasanna's Work

- "I Don't Paint To Live, I Live To Paint": Willem de Kooning

- Salvador Dali Retrospective: I am Delirious, Therefore I am

- To Be Just and To Be Fair

- Census of Senses: Investigating/Re-Producing Senses?

- Between Worlds: The Chittaprosad Retrospective

- Awesomely Artistic

- Random Strokes

- Counter Forces in The Printmaking Arena and how to Counter them

- Shift in focus in the Indian Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

A Physical Perception of Matter

Volume: 4 Issue No: 21 Month: 10 Year: 2011

Feature

The Prints of RM Palaniappan

by Koeli Mukherjee Ghose

RM Palaniappan has to his credit 19 solo shows across India, as well as shows that have travelled to Holland and the U.K. He was born in 1957, in Devakottai in Tamil Nadu. Palaniappan studied at the Govt. College of Arts Crafts in the late 70's and in the year 1991 he studied advanced lithography at the Tamarind Institute (U.S.A), and later went on to Artist in Residence at Oxford University in 1996. He received a Fulbright Grant from the U.S. Educational Department,  the Charles Wallace India Trust grant, an International Visitorship programme from the USIS, and a Senior Fellowship from the Government of India. Cultural wings in France, Germany and Australia have invited him to visit. Adding to this, he has been invited to conduct workshops at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, University of New Mexico, Indiana State University and Kansas State University in the USA, as well as the Royal College of Arts in London and M.S. University, Baroda. And somehow still, in the course of his travels, he has found the time to visit museums and galleries in the USA, UK, France, Germany, Australia, and Sweden...cruise to Italy, Turkey, Greece and Croatia...and receive awards for prints at Biennales in Bhopal and Taiwan!

the Charles Wallace India Trust grant, an International Visitorship programme from the USIS, and a Senior Fellowship from the Government of India. Cultural wings in France, Germany and Australia have invited him to visit. Adding to this, he has been invited to conduct workshops at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, University of New Mexico, Indiana State University and Kansas State University in the USA, as well as the Royal College of Arts in London and M.S. University, Baroda. And somehow still, in the course of his travels, he has found the time to visit museums and galleries in the USA, UK, France, Germany, Australia, and Sweden...cruise to Italy, Turkey, Greece and Croatia...and receive awards for prints at Biennales in Bhopal and Taiwan!

The concept of movement for him is not physical; rather it is the idiom of matter with all the potentialities and intricacies of psychological and metaphysical reading. In his works the creation of a sign and its deciphering happens almost involuntarily...something the artist does while contemplating the image in order to express a space. Palaniappan's space is remotely documented. He says, “I use space and symbol almost subconsciously, as if there was some primal recognition.” Some of the numbers he uses call to mind military code, along with the architectural patterns that enthral him.

RM. Palaniappan's post-modern implications are significantly appropriated in his personalized graphic works, expositioned in a concentrated series of visual research, indissoluble from the artist's affinity to science.  Betrothed to the dialogue of his conciliation of space in the course of his working out subtle hypothesises, he attempts to comprehend the affiliation between man and universe; the contemporary problems in perceiving psychological and physical matter. Thus Palaniappan essentializes his notion of space as a working together of actualities. These realities are experienced in thoughts, emotions and the sensations he is subjected to, both actually and sensitively, at the very point of time the line is drawn.

Betrothed to the dialogue of his conciliation of space in the course of his working out subtle hypothesises, he attempts to comprehend the affiliation between man and universe; the contemporary problems in perceiving psychological and physical matter. Thus Palaniappan essentializes his notion of space as a working together of actualities. These realities are experienced in thoughts, emotions and the sensations he is subjected to, both actually and sensitively, at the very point of time the line is drawn.

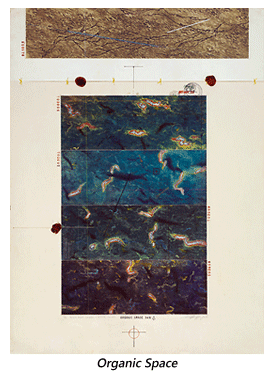

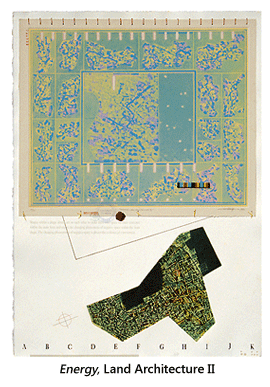

In the beginning Palaniappan employed soft ground etching for crisp linear effects. Later, for his mixed media, he would apply paint and then scrape it. He would often use graphs and ballpoint pen to write and draw, along with typing codes. This was more to record an idea or an emotion using notations, drawings, marks, ciphers, and signs. At times it would be spontaneous, but by and large order prevailed. Cryptograms, graph papers, and printed images were put to use in achieving a robust measures of graphic quality. He consciously started to paint and write numbers on the works. He would choose to make notations and jottings in the area surrounding the print, as if they were drawings in a scientist's diary. Although it is thought mandatory that the space around a print must be kept clear, he engaged it in evolving an individual system to define the space by his free will. Palaniappan informs that his numbers could also be interpreted as personal code. Later the artist used cellophane tape and stamps with various seals to add collage elements.

Palaniappan says, “The metal plate for etching is like a jewel to me. I would travel in the plate. I would carve the plate like a goldsmith. For many years physical, psychological reality and metaphysics dominated my work. My first visit to the United States was a long trip and I took many flights. I used to take pictures from the windows and I have thousands of aerial photographs. Rivers became lines. From 1992 to 1997 I concentrated on those shapes. The importance of shapes is the negative space versus the positive space. So the material choices were instinctive according to the need. Once I conceive everything, contemplation thereafter leads me to abstract them…this abstraction is inseparable from the thought process.”

The artist's lines make evident his consciousness as he works on the paper allowing the hand to move at his unconscious command and yet not unthinkingly, speaking the abstractionists language. The consequential arrangement that apparently seems non-representational, eloquently realizes an internal diagram that is determined, sensuous, and chronicles a seismic graph of spasms from the inner core. This awareness of the constant process which acts as the stimuli is both external and internal in nature, and is identified as the issue and the action. A plethora of information in terms of specific image and abstracted  elements throw light on the distinct break-up in engagement. While the recipient of the image is perplexed with the signs, the artist asserts his experiences in their truest form.

elements throw light on the distinct break-up in engagement. While the recipient of the image is perplexed with the signs, the artist asserts his experiences in their truest form.

The theorization of the abstract negotiations of time and space in Palaniappan's works mark them as the birth of a future in the present situation. In a sense his works conceal a notion, which in the postmodern age is perceivable as subjective knowledge. Palaniappan hypothecates that the threshold of the mind space or the conceptual space makes existence viable. In his images the problem of the space and line is addressed in the foreground. Although the conceptual space and the sensational space both are brought into play, it is the conceptual space that activates the constant process.

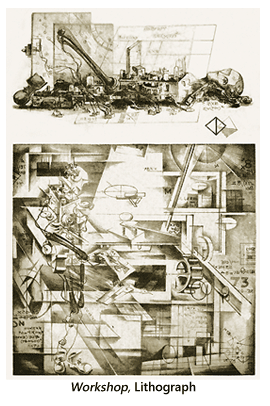

As common to a generation born in India during the 1960's, the flux of war movies from the western world noshed his earlier images. These recollections emerged as numbers, maps, and architectural patterns; sites marked for aerial attacks. Fascinated by the technology of printing in his father's tin printing unit in Madurai, Palaniappan turned to printmaking in college. During the early 1980's his images were premised on descriptive diagrams, akin to those used in the study of science. This inculcated a new way of incorporating visual information from his experiential environment and imbibing them with pictorial possibilities in a breathing existence. His series of calendars that he produced in the mid 1980's were an inspired play with pictures of landscapes from a calendar printed in Germany. The ready images were contemplated as if on a dissection tray. Palaniappan, became absorbed in selecting and removing portions of them and renegotiated the existing portions of the images with his drawings, code numbers and calculations. The mixed media works of 1979-80, on paper and using lithographs, depicted the detailed frameworks of the aircraft that engrossed him. He developed a series of skeletal drawings that centred around the dynamic elements along with the details of the mechanisms. The "flying skeleton" that the artist used depicted the aircraft as seen from underneath. During this time Palaniappan was studying cubism and he appropriated the cubist aesthetics to render the front ends (noses) of the aircrafts.

In his lithograph tilted Workshop he explored the idea that man and machine were in each other's pocket. He delved into the juxtaposed skeletal and cubist forms: of a man lying down, a printmaking workshop, and the artist. Dynamic expression and movement gained ground with the composite image of the bird with the wings of an aircraft, lending an involuntary conceptual interweave to the image. The flying man series, done in black and white prints, contemplated upon a wishful freedom from a mechanized life. In 1985 the Alien Planet series of sixteen colour prints using the viscosity method and mixed media ensued.  These forms were essentially circular shapes depicting variegated interpretations of perceptions of matter by human minds. Thus the physical reality of the earlier phase gave in to the idea of space in the later works. Palaniappan has pressed upon the need for an unrestricted freedom for employing the graphic medium to achieve contemporary eloquence. His free-spirited line and the arrangement of different collage materials on the print developed during this time, a process he used to express relationship of movement and perception.

These forms were essentially circular shapes depicting variegated interpretations of perceptions of matter by human minds. Thus the physical reality of the earlier phase gave in to the idea of space in the later works. Palaniappan has pressed upon the need for an unrestricted freedom for employing the graphic medium to achieve contemporary eloquence. His free-spirited line and the arrangement of different collage materials on the print developed during this time, a process he used to express relationship of movement and perception.

Between 1990 and 1996 Palaniappan pursued the idea of effectively depicting his own concern toward negative space and its value in terms of physical and psychological perceptions. He explains the related phenomenon with an example, “As you put objects of different shapes inside a glass bottle and stir and shake the bottle, all the positive shape inside the bottle will move and the changing phenomenon of the negative space inside the bottle is always the evidence of a movement.” Later in 1996, due to his frequent overseas travel, his interest in maps and architecture brought forth a vast range of drawings and digital prints.

During his visit to Germany in 1999, while walking and photographing around the Reichstag at Berlin, the artist felt a deep emotional recall of World War II. Although its traces were totally out of sight, Palaniappan perceptively experienced an evocation of images of the World War just as he had seen in the war films in his early days. A sequence of graphics, mixed media, and drawings ensued after his return, resulting in a further tilling of the experiences of Germany and the Reichstag at Berlin.