- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Rita Datta

Africa my Africa

Africa of proud warriors in the

ancestral savannahs

Africa my grandmother sings of

Beside her distant river

I have never seen you

But my gaze is full of your blood

Your black blood spilt over the fields

The blood of your sweat

The sweat of your toil

The toil of your slavery

The slavery of your children

Africa, tell me Africa,

Are you the back that bends?

Lies down under the weight of

humbleness?

The trembling back striped red

That says yes to the whip on the roads

of noon?

Solemnly a voice answers me

“Impetuous child, that young and

sturdy tree

That tree that grows

There splendidly alone among white

and faded flowers

Is Africa, your Africa. It puts

forth new shoots

With patience and stubbornness puts

forth new shoots

Slowly its fruits grow to have

The bitter taste of liberty.”

Though David Diop (1927-1960), the writer of this iconic poem, didn't coin the term Negritude, it embodies both Black ideology and the protest of the 20th century most succinctly. It's not just race pride that the poet wishes to highlight, though he certainly does that, particularly in the last stanza, calling attention to “that young and sturdy tree” among “white and faded flowers” that “puts forth new shoots”. It both predicts the decline of Europe and speaks of hope for all colonial peoples forming independent nation-states between the late-1940s and the 1960s. Hence, it goes beyond the struggle for black dignity and becomes the anthem of the oppressed everywhere.

How relevant it can be to the subcontinent is seen when you compare the above poem with what the first nationalist poet of India had written.

My country! In thy days of glory past

A beauteous halo circled round thy

brow

and worshipped as a deity thou wast–

Where is thy glory, where the

reverence now?

Thy eagle pinion is chained down at last,

And grovelling in the lowly dust art thou,

Thy minstrel hath no wreath to weave for thee

Save the sad story of thy misery!

Well-let me dive into the depths of

time

And bring from out the ages, that

have rolled

A few small fragments of these wrecks

sublime

Which human eye may never more

behold

And let the guerdon of my labour be,

My fallen country! One kind wish for

thee!

The writer is, of course, Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, though his tone is of lament rather than hope, because he wrote more than a century before Diop. But it does seem that the oppressed speak the same language of protest just as oppressors follow the same methods of persecution. But Negritude symbolizes protest against white hegemony for much of the world because class, race and national identity seem to come together in this ideology.

It is popularly thought that the term Negritude itself was coined by one of the leading black intellectuals from the French Caribbean, Aime Cesaire (1913 2008), who anticipated post-colonial studies in his Discourse on Colonialism But the generation that came after him could be less self-conscious in its embrace of black culture and an African identity questioning, as the Nigerian artist Dil Humphrey-Umezulike does, the civilization that was foisted on them by imperial masters..

Earlier black writers like Diop or Cesaire or Leopold Senghor (1906-2001), who became President of Senegal in 1960, simultaneously embody the immanent irony of the colonized. Like the Indian National Congress leaders who adopted constitutional models in claiming a share of the power, the writers of the nascent black awakening of the 1920s and 1930s proved that the subaltern must speak the language of the oppressor to be heard. Like the Turkish astronomer in Saint Exupery's (1900-1944) Little Prince, whose discovery of Asteroid B-612 was ignored at the International Astronomical Congress until he went in European attire, these blacks wore suits.

Incidentally, that's what Gandhi wore, too, before the peasant's loin cloth and chador became his quiet equivalent of a mailed fist. Indeed, that astute leader knew what an affront to authority one's dress and footwear could be. Particularly when he must be met on equal terms by somebody as exalted as the Viceroy. The subversive content of mere attire can be seen in Winston Churchill's (1874-1965) reaction to the “half-naked fakir”. When he was asked about his scanty clothing by British journalists, Gandhi's retort was witty but a retort nevertheless: you have your plus fours, we have our minus fours.

The question of dress brings up the hijab which Europe is so worked up about right now. Many Muslim women have decided to don it in the West as an identity statement. And the West, traditionally intolerant of deviation, feels threatened because the simple head scarf defies the attempt by the State and society to bring about a seamless assimilation so that the Afro-Asian migrants in Europe fulfil Macaulay's (1800-1859)dream and become sahibs in all but colour.

But then, the purdah is indeed a tool of gender subjugation in male diktats. For consider how Nazar Sajjad Hyder (1894-1967) uses ridicule of male possessiveness as sharp protest in the following lines. “....their hearts do not desire that their wives should come or go anywhere beyond their controlling vision. Even if there are a hundred thousand purdahs, they fear that another's look may fall upon them. Who knows? If the curtain of the carriage flies up, if their wife's voice is heard by another, that would be disaster indeed!....Because they take undue advantage of their own liberty…..men fear that if the women are given freedom, they will also become like them. Therefore…..keep the women confined.” (Women Writing in India, ed. by Susie Tharu and K. Lalita, Oxford India Paperbacks)

A significant contribution to non-fiction literature that must be mentioned here came from Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), whose Wretched of the Earth became a Bible of decolonization to the 1960s generation. One of the things that Fanon describes in it is the unofficial apartheid followed in African colonies where settlers and natives lived in “reciprocal exclusivity”. But while the settlers' town was well-lit, clean and well-fed, the native town, “for niggers and dirty Arabs”, was dark, dirty and starving. In this context Ubu Roi and the Truth Commission-a take on Alfred Jarry's (1873-1907) burlesque Ubu Roi-can be recalled. The writer Jane Taylor and the director William Kentridge collaborated to produce a piece of inventive theatre that combined puppetry, music and documentary excerpts with live actors to “retrieve lost histories” that had been glossed over by the white regime in South Africa. How that remarkable South African artist, Kentridge, makes shadows speak can be gauged even by looking at individual frames.

But it's a mistake to see apartheid only as an instrument against blacks. Susan Nathan's revealing book, The Other Side of Israel, confirms Fanon's description but in the context of the Israeli state's treatment of its Arab citizens. The Jewish author exemplifies civil society's recoil at the systematic discrimination against and segregation of Arabs who are also poor, making her expose something of an inheritor of Fanon's legacy. It only proves that yesterday's victim can slip into the role of today's tormentor when conditions change. Interestingly, Kentridge agreed to have a retrospective in Israel last year, but unequivocally condemned its policy on Palestine once there.

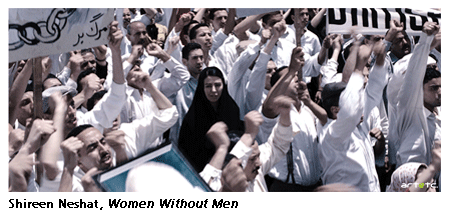

The Middle East continues to simmer, however, with the nuclear arms issue further confounding what was already complex. Two women artists of this region who convey the sense of a tight, tense, despairing vulnerability are the London-based Palestinian, Mona Hatoum, and the New York-based Iranian, Shireen Neshat. Hatoum started off with agitprop performances but her later work is the more sinister for its reticence. An installation with gunny bags that are stacked like barricades and overgrown with grass and weeds is rich in ambiguity, insinuating a range of suggestions, from the political to the philosophic. Her construction of a stark grid that evokes a cage and confinement throws moving shadows that loom insidiously from the walls around, leaving an inchoate unease. And the film, video and photography artist Neshat creates images that haunt you with their mix of grim silence and embattled fragility. Her debut feature film, Women Without Men, revisiting her enduring themes of gender politics in a traditional and troubled Muslim society, is yet to be seen in India. Such artists, those who use the new media and the new forms the computer, video, film, Conceptual art, performance, photographyprobably predict the future of expression that protest would demand, though painting and sculpture can never be outdated.

The Middle East continues to simmer, however, with the nuclear arms issue further confounding what was already complex. Two women artists of this region who convey the sense of a tight, tense, despairing vulnerability are the London-based Palestinian, Mona Hatoum, and the New York-based Iranian, Shireen Neshat. Hatoum started off with agitprop performances but her later work is the more sinister for its reticence. An installation with gunny bags that are stacked like barricades and overgrown with grass and weeds is rich in ambiguity, insinuating a range of suggestions, from the political to the philosophic. Her construction of a stark grid that evokes a cage and confinement throws moving shadows that loom insidiously from the walls around, leaving an inchoate unease. And the film, video and photography artist Neshat creates images that haunt you with their mix of grim silence and embattled fragility. Her debut feature film, Women Without Men, revisiting her enduring themes of gender politics in a traditional and troubled Muslim society, is yet to be seen in India. Such artists, those who use the new media and the new forms the computer, video, film, Conceptual art, performance, photographyprobably predict the future of expression that protest would demand, though painting and sculpture can never be outdated.

The Jewish question, the treatment of the blacks and the Middle East have been motifs that dominated a major part of political discourse and activism in the 20th century. That maverick director, Steven Spielberg, a Jew, reacted to two kinds of injustice in two films that would surely rank among the most affecting. One is, of course, Schindler's List. The concentration camp for Jews in it has nightmarish reconstructions of what the inmates were made to do by the Nazis. The director's choice of making it in black and white stripped it of prettified elements and lent it the illusion of a documentary.

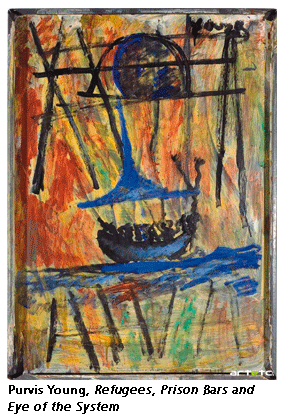

The other, Amistad, may not be as well known in India but it re-tells an historical event. The name comes from a Spanish slave ship where a rebellion of abducted Africans led to a gripping drama both cerebral and emotional. Because there was not enough place in the ship's hold to keep all the blacks the ship owners had captured, they were piled on like luggage. And when it was seen that the ship needed to shed weight, some of the captives were chained together and thrown into the sea! Intriguingly, the brittle little boat in African-American artist Purvis Young's Refugees Prison Bars….., tossed about in a chaos of frenzied strokes, becomes a visual correlative of the Amistad as it drifted towards America's east coast after the slaves managed to free themselves and killed most of the Spaniards on board. The refugees Young probably had in mind were hapless boat people from Haiti, Cuba and so on, who didn't have a warm welcome awaiting them. For they were thought to be human detritus.

If Indians shudder at race discrimination, counting themselves among the victims of white rule, they forget the silent apartheid traditionally practised in the subcontinent. For what was the caste system if not apartheid? Toni Morrison's strangely clinical description of slavery in her Pulitzer-winning Beloved wouldn't be inappropriate if race were replaced by caste except that the low castes in India had the freedom to run away. The caste system has always followed a severe, multiple-tiered apartheid in confining each caste to its own little slot in life and its own little section on the edge of the village. But the idea of caste differences had co-opted the privileged who benefitted by this arrangement. Hence, no protest could have anything but a temporary and partial effect.

Nevertheless, protest against one of the oldest forms of human rights abuse there indeed was, in different ages. In fact, the role of religion and religious cults in extending the language of protest doesn't always come to mind in association with a word that immediately evokes slogans, speeches and processions. But Buddhism and Jainism embodied the discontent of non-Brahmins against rigidified caste in the context of the fluid economic changes of 6th century BCE.

One of the marginalized groups who sought dignity in the Buddhist order and found a voice was of women who joined nunneries even though the Buddha nursed misgivings about permitting them to do so. But despite the restrictions imposed by the Sangha on them, women did join it in large numbers for that offered an escape from the prison of domesticity. The Therigatha or the songs of the theris or nuns records the sense of liberty they experienced.

Mutta, for example says,

So free am I, so gloriously free,

Free from three petty things–

From mortar, from pestle and from my

twisted lord…..

In other words, joining the Sangha and then writing about it certainly was a defiant gesture against gender bias in Later Vedic society. The same sentiments are repeated by Sumangalamata in the following lines;

A woman well set free! How free I am,

How wonderfully free, from kitchen drudgery….

(both quotations from Women Writing in India)

Centuries later, in the medieval age came the Bhakti saints whose gentle resistance of Brahmanical norms is treasured in the couplets of a saint who most exemplifies the best syncretic values of the movement. Unlike Mahavir and Gautam Buddha, who were sons of Kshatriya chieftans, Kabir (1440-1518) was a social outcast. His illegitimacy, Brahmin birth, Muslim upbringing and poverty so scramble his identity as to make his life itself a message of upturned upper caste assumptions.

Around the same time Bengal, then ruled by Hussain Shah, came under the spell of a young man named Nemai (14861534) who, by his opposition to the caste system, had provoked the wrath of Kali-worshipping Brahmins in much the same way as Jesus, to go by the New Testament, had angered the Pharisees and Scribes. And just as the last had wanted the Roman governor to crucify Jesus, the Brahmins wanted Nemai and his followers brought to their knees by the Muslim magistrate or Qazi. The Qazi is said to have banned the Vaishnavas' sankirtan or processions with singing of devotionals accompanied by frenzied dancing. However, it is said that Nemai launched a civil disobedience movement and led a huge sankirtan to the Qazi – who, incidentally, was a friend of his maternal grandfather – to protest the ban and had got it reversed.

Of course, it isn't often that you hear of kirtan as protest but African-American spirituals did have an important role in awakening black consciousness. It is now generally acknowledged that music and dance can be therapeutic. By helping to loosen inhibition and suspend cold logic, music and dance become instruments of protest that can be voiced obliquely. The work songs that have been seen to exist in most communities were ways of getting through back-breaking schedules fixed by the masters or their supervisors by inducing some sort of spell on the workers themselves to provide a distraction and relief. The Blues that evolved from the African-American work songs are a case in point. Jazz and its exciting syncopation and earthy, throbbing rhythm drums and haunting saxophone get under the skin with their sad, resigned, rebellious, mocking tones. Not for nothing would jazz be called “freedom music”.

The one album to cite here has to be the 1960 We Insist! Freedom Now Suite of Max Roach (1924-2007). This is what an online BBC review by Nick Reynolds says about it in one place: 'Roach was active in the civil rights movement in the US throughout his life and the Freedom Now Suite is a musical history lesson. It starts with the sombre, shocking slave chant of “Driva' Man” which takes you right into the heart of oppression, and ends back in Africa with “Tears For Johannesburg”'.

Inspired by the same kind of marginal and oral tradition in India, the IPTA welcomed songs by such writers as Salil Choudhury to identify with fisher folk or peasants to underline the need for an azaadi that would be egalitarian in its restructuring of power and resources and not jhuta, by merely replacing rulers but leaving the Britsh system intact. Songs like Dhaan Katar Gaan or Nouka Bawar Gaan, sung in Bengali by Hemanta Mukherjee, are infectious in their virile artistry despite the touch of the sentimental in the words. Incidentally, the man-made famine of 1942 brought forth disturbing images from Somnath Hore, Jainal Abedin and Chittaprasad.

While on music, it wouldn't be out of place to remember the nationalist songs that fuelled India's struggle against imperialism. Like Rang de Basanti, for example. But the song that was aimed at a specific measure of the government, the partition of Bengal, in 1905, was Tagore's Bidhir Bandhon Katbe Tumi. Ultimately, no song could prevent the partition of the land in 1947, of course. But protest could not be silenced in a region of volatile passions and perpetual rebellion whose icon was Nazrul Islam, the permanent Bidrohi or rebel. This was discovered by the new rulers of Pakistan when Urdu was imposed on its eastern province and a new movement, the bhasha andolan began in 1952. No recall of protest gestures could be complete without the mention of Amar Bhaier Rokte Rangano Ekushey February, written by Abdul Gaffar Choudhury, for it commemorates linguistic nationalism and asserts not only the pride of all Bengalis in their language but wrests from language fascists a respect for local culture. By declaring February 21 as International Mother Language Day, UNESCO acknowledged the role of Bangladesh in jolting the world into an awareness of how fluid identities are, throwing up competing loyalties that can turn recessive or assertive by turns, depending on what is at stake.

Speaking of India's eastern neighbour calls for a mention of a powerful film from its western neighbour. Since it was released in India, chances are that serious audiences have seen Shoaib Mansoor's Khuda Kay Liye (2007) which packs a double-edged punch: as much against the USA's brutal treatment of suspects after 9/11 as against jihadi insanity. Though fictionalized, its stand must be deemed bold. Michael Moore's celebrated documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), of course, indicted the Bush administration for the invasion of Iraq in violation of international law, though the American media was hesitant to do so, going along with the myth of the Weapons of Mass Destruction. The film referred, of course, to Francois Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451, which is the temperature at which paper burns. This 1966 film about a scary, Kafkaesque omniscient, omnipotent State of the future, makes a point that's simple and profound at once: that free thought, which takes civilization forward, frightens the powerful but the dialectics of history are beyond the control of even the worst police state.

Anti-war poetry and the voice of the Beat generation represented by Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), John Lennon (1940-1980), Yoko Ono, the flower children and the peaceniks defined the 1960s with Vietnam which became America's first nemesis urging a whole lot of expressions of protest. One of the songs that spoke for reluctant draftees and students was I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag written by Joe McDonald and has this cynical levity, which is the inversion of deep anxieties buried under a youthful spirit.

Well, Come On All Of You, Big Strong

Men,

Uncle Sam Needs Your Help Again.

He's Got Himself In A Terrible Jam

Way Down Yonder In Vietnam

So Put Down Your Books And Pick Up

A Gun,

We're Gonna Have A Whole Lotta Fun.

And It's One, Two, Three,

What Are We Fighting For ?

Don't Ask Me, I Don't Give A Damn,

Next Stop Is Vietnam

The Vietnam War exposed the American policy of containment of Communism as the typical brash, overweening, arrogant muscle-flexing of a superpower that refused colonial peoples the right to shape their own destiny. Big Brother was going to do it all for them, never mind if the disobedient adults were half a world away and striving to gain independence from a foreign country, France. They must still be taught a lesson. But when the body bags began to arrive, American smugness began evaporating.

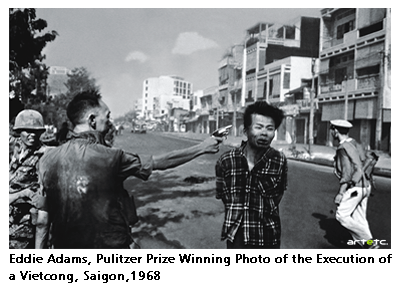

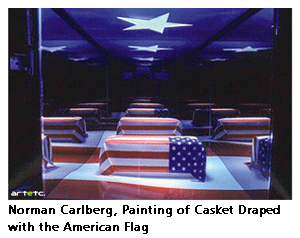

This was the golden time of poster art with slogans that screamed Amerika is Devouring its Children. Norman Carlberg's painting of caskets draped with the American flag placed in receding rows is imbued with a respectful silence and a hushed light that turn what is just a geometric arrangement bereft of human presence into a compelling reminder of the price of war and who pays it. The chill of this work contrasts with the heart-rending charge of the black and white photograph by Horst Faas which caught a distraught South Vietnamese father looking up questioningly at a truckload of South Vietnamese soldiers as he holds up the body of his little child, killed by a bullet. This and other frozen frames from the war theatre like Eddie Adams' (1933-2004) Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of the execution of a Vietcong in 1968 are all that remain of a long-drawn conflict in an age when the TV camera hadn't invaded every battlefield and bedroom. If the general atmosphere of anger, of youthful rebellion entered Antonioni's (1912-2007)1970 film Zabriskie Point, whose last scene is cathartic, imagining the colourful explosion of a realtor's elegant home, the Bread and Puppet Theatre's anti-war spectacles crossed the barrier of age in adopting what is essentially children's entertainment for a serious political agenda.

This was the golden time of poster art with slogans that screamed Amerika is Devouring its Children. Norman Carlberg's painting of caskets draped with the American flag placed in receding rows is imbued with a respectful silence and a hushed light that turn what is just a geometric arrangement bereft of human presence into a compelling reminder of the price of war and who pays it. The chill of this work contrasts with the heart-rending charge of the black and white photograph by Horst Faas which caught a distraught South Vietnamese father looking up questioningly at a truckload of South Vietnamese soldiers as he holds up the body of his little child, killed by a bullet. This and other frozen frames from the war theatre like Eddie Adams' (1933-2004) Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of the execution of a Vietcong in 1968 are all that remain of a long-drawn conflict in an age when the TV camera hadn't invaded every battlefield and bedroom. If the general atmosphere of anger, of youthful rebellion entered Antonioni's (1912-2007)1970 film Zabriskie Point, whose last scene is cathartic, imagining the colourful explosion of a realtor's elegant home, the Bread and Puppet Theatre's anti-war spectacles crossed the barrier of age in adopting what is essentially children's entertainment for a serious political agenda.

The 19th century, the age of industrialization, of tumultuous social transformation was a phase when British imperialism had reached its zenith, Christianity was confident that it was the only true path, and whites were convinced of their superiority moral, technological, intellectual. But this was also the age when surface glitter couldn't completely conceal the dark underbelly of urban lowlife and the unjust social order that coexisted with professions of high principles, so tellingly depicted by Dickens (1812-1870) in his novels, by Hugo (1802-1885) in Les Miserables and by Zola (1840-1902) in Germinal. A play that is rarely remembered must also be mentioned for its withering spotlight on the effects of industrialization in Germany. It was Gerhart Hauptmann's (1862-1946) The Weavers which did something unusual: stripped it of a hero to concentrate on the “mob”, uncovering both the pathetic poverty of the weavers and the unscrupulousness of their exploiters.

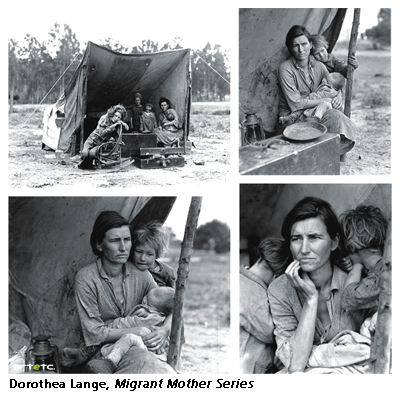

No doubt, the most important tract of the 19th century that was both protest and a primer of revolution was, of course, The Communist Manifesto. Communism was to motivate much protest and positive action all over the world. And its prediction of cyclic crises in capitalism seemed to come true when the Great Depression caught America by surprise. While the Depression brings Chaplin's Modern Times to mind, the one image that came to summarize this period was a simple photograph: Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). The woman's lined skin, worried concentration, unkempt hair and frayed cardigan combine with her tense pose, the right hand with its broken nails raised to her cheek, to give Depression a living face, the face of a Mother Courage. What makes the work particularly eloquent are the two children who bury their faces at the mother's shoulders. It might be of interest to cite another famous work by Lange which captured the American government's move to make Japanese school children in San Francisco pledge allegiance to the Stars and Stripes after the USA entered the Second World War. This, as well as images of the internment of the Japanese Americans, were impounded by the Army because they were recognized for their criticism of government policy.

No doubt, the most important tract of the 19th century that was both protest and a primer of revolution was, of course, The Communist Manifesto. Communism was to motivate much protest and positive action all over the world. And its prediction of cyclic crises in capitalism seemed to come true when the Great Depression caught America by surprise. While the Depression brings Chaplin's Modern Times to mind, the one image that came to summarize this period was a simple photograph: Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). The woman's lined skin, worried concentration, unkempt hair and frayed cardigan combine with her tense pose, the right hand with its broken nails raised to her cheek, to give Depression a living face, the face of a Mother Courage. What makes the work particularly eloquent are the two children who bury their faces at the mother's shoulders. It might be of interest to cite another famous work by Lange which captured the American government's move to make Japanese school children in San Francisco pledge allegiance to the Stars and Stripes after the USA entered the Second World War. This, as well as images of the internment of the Japanese Americans, were impounded by the Army because they were recognized for their criticism of government policy.

But Communism, which had awoken visions of a new world order, borders melted away, didn't turn out to be in practice what it was in theory. The free voice was stifled in the USSR and China, artists and writers were either forced into exile like Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) was, or jailed, the fate of Ai Weiwei in China. That master playwright, theorist and Marxist, Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), wrote that his Life of Galileo showed the “dawn of a new age”. But can we take this too readily as a note of undying optimism when we remember one of his poems?

I was sad when I was young

And sad now I am old

So when can I be gay for once

It had better be soon.

Capitalism and Communism are, of course, both descended from the same intellectual tradition of the West. If a sensitive, creative mind rebelled against Western civilization itself, he would actually have to turn his back on it and embrace the lost innocence of a primitive age. And that was what Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) had done. In a gesture of enduring protest.