- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

The Inner Voice

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Tanya Abraham

Protest art in a contemporary sense calls for the use of art as a medium to project and express an innate idea which is eventually bound to create a shift in the understanding of the public. It, in many ways, is a silent form of portraying a thought without the adaptation of extreme means simply put, art takes the place of a spokesman for the artist, juxtaposed with the artist's personal style. Modern protest art rose to high focus especially in the sixties, when art found space beyond galleries and museums and positioned themselves in places freely accessible to the public. In India, although the use of art (to protest) has been rather gradual in comparison to other countries of the world, the idea has been welcoming. Artists have been using art (both visual and performing) to bring about positive change - It has proven to be an ideal form of telling the artist's strong beliefs, which opens a new arena of understanding. One must, however, recognize that protest art can be of public nature or one which is private: an issue which moves beyond the artist alone and affects equally a society or a community. Or it could as well be the artist's personal protest of an environmental or social existence which has created a (personal) negative impact. The mediums, and use of these mediums in protesting are varied and wide, and change from culture to country each created for a specific reason. Whether these have been successful or not is a question by itself, but using a medium which arouses the senses is proven to be an effective method of protest and art is a strong way for it.

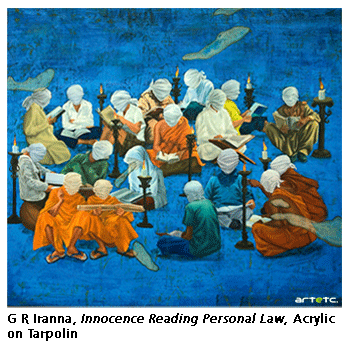

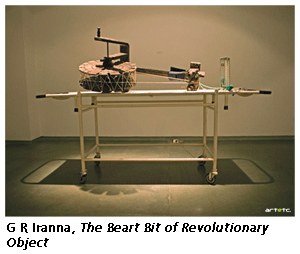

In India, the socio-economic scenario is so intricately woven and flavoured with cultures and traditions, the complexities involved in a diverse country as it, brings forth multifarious thoughts. Art used to speak thus changes immensely from artist to artist, each influenced by his own surrounding: for example, in G R Iranna's solo show titled Birth of Blindness, fibre glass and cloth sculptural installations and paintings tell of spiritual and sensory deprivation. He harps on the lack of psychic and physical restraint. In Make Sure You are Breathing, a naked man with a burlap bag covering his arms and head depicts his inability to maneuver his environment and is a symbol of his aimlessness. Iranna's installations tell of human existence, which is so deeply influenced by situations and are often beyond one's control. Where intuition and spiritual awakening lies dormant, and man is dictated by external forces. In his Dead Smile, which is an installation of numerous nude males squatting on the floor with their hands resting on their knees outstretched and faces covered in cloth, are an expression of lost humans oblivious to the world outside. Wrapped in silence, the figures show the lost human race which has become part of an industrialised, mechanic world and a mass society. Communication to each other is absent; instead, lives are dictated by the world outside. Iranna harps on not only the unawareness of human consciousness but also the presence of one's inner voice. He speaks of the individual and the individual's connection to the universe, rather than a specific social scenario. In Birth of Blindness where blind folded figures are prostrate on the ground, the artist questions the position which religions hold, again blinded by details which are far away from one's spirituality. He expresses his thoughts on humans tendencies to act without thinking or deciphering, instead moving forward blindly into a state of senselessness and ambiguity. In his Innocent Reading Personal Law, the artist depicts the same idea, as men whose heads are wrapped in cloth are engrossed in the studying of texts which enumerate the laws of life. Iranna again points out how humans are chained to strict demands, oblivious to the truth that surrounds them. In Pray (1) he uses the idea of an organized team, who are ready for a game (like the game of life) while, his installation Garden of Dead Flowers depict both holy men and a life of purity and simplicity. Iranna questions the loss of spirituality, the loss in the connection between the spirit and the eternal. He also throws light on the effects of terrorism on lives. Through metaphors he aims to recall peace which was once propagated. His protest is clearly a protest of his understanding of life and the presence of the ever prevailing. His art also questions its absence, and the lack of humanness in men. Time and again Iranna's works speak of an organized society In his words: 'In the name of civilization, territorial aggressions, ideological indoctrinations, homogenization of tastes etc are violently inflicted upon human beings. This is to bring world order.' This is well depicted by his installation of a weary donkey, carrying sharp tools in a saddle. Worn out, the edges of the tools are bandaged and blood stained ironically Iranna says the tools here represent the transition from a society of innocence to a industrialised one, the tools bearing the brunt of change and thus metaphorically 'the actual victims of civilization violence'. Iranna continues, “The image of the donkey could either represent silent sufferings of 'subjects', the dumbness resulting from homogenisation of this world or even passive witnessing of the world. As an artist, I feel that it is important to bring in socio-cultural and politico-economic issues involved in a fast changing world.”

In India, the socio-economic scenario is so intricately woven and flavoured with cultures and traditions, the complexities involved in a diverse country as it, brings forth multifarious thoughts. Art used to speak thus changes immensely from artist to artist, each influenced by his own surrounding: for example, in G R Iranna's solo show titled Birth of Blindness, fibre glass and cloth sculptural installations and paintings tell of spiritual and sensory deprivation. He harps on the lack of psychic and physical restraint. In Make Sure You are Breathing, a naked man with a burlap bag covering his arms and head depicts his inability to maneuver his environment and is a symbol of his aimlessness. Iranna's installations tell of human existence, which is so deeply influenced by situations and are often beyond one's control. Where intuition and spiritual awakening lies dormant, and man is dictated by external forces. In his Dead Smile, which is an installation of numerous nude males squatting on the floor with their hands resting on their knees outstretched and faces covered in cloth, are an expression of lost humans oblivious to the world outside. Wrapped in silence, the figures show the lost human race which has become part of an industrialised, mechanic world and a mass society. Communication to each other is absent; instead, lives are dictated by the world outside. Iranna harps on not only the unawareness of human consciousness but also the presence of one's inner voice. He speaks of the individual and the individual's connection to the universe, rather than a specific social scenario. In Birth of Blindness where blind folded figures are prostrate on the ground, the artist questions the position which religions hold, again blinded by details which are far away from one's spirituality. He expresses his thoughts on humans tendencies to act without thinking or deciphering, instead moving forward blindly into a state of senselessness and ambiguity. In his Innocent Reading Personal Law, the artist depicts the same idea, as men whose heads are wrapped in cloth are engrossed in the studying of texts which enumerate the laws of life. Iranna again points out how humans are chained to strict demands, oblivious to the truth that surrounds them. In Pray (1) he uses the idea of an organized team, who are ready for a game (like the game of life) while, his installation Garden of Dead Flowers depict both holy men and a life of purity and simplicity. Iranna questions the loss of spirituality, the loss in the connection between the spirit and the eternal. He also throws light on the effects of terrorism on lives. Through metaphors he aims to recall peace which was once propagated. His protest is clearly a protest of his understanding of life and the presence of the ever prevailing. His art also questions its absence, and the lack of humanness in men. Time and again Iranna's works speak of an organized society In his words: 'In the name of civilization, territorial aggressions, ideological indoctrinations, homogenization of tastes etc are violently inflicted upon human beings. This is to bring world order.' This is well depicted by his installation of a weary donkey, carrying sharp tools in a saddle. Worn out, the edges of the tools are bandaged and blood stained ironically Iranna says the tools here represent the transition from a society of innocence to a industrialised one, the tools bearing the brunt of change and thus metaphorically 'the actual victims of civilization violence'. Iranna continues, “The image of the donkey could either represent silent sufferings of 'subjects', the dumbness resulting from homogenisation of this world or even passive witnessing of the world. As an artist, I feel that it is important to bring in socio-cultural and politico-economic issues involved in a fast changing world.”

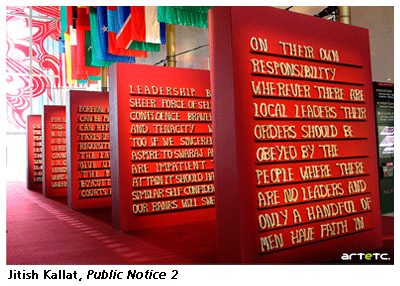

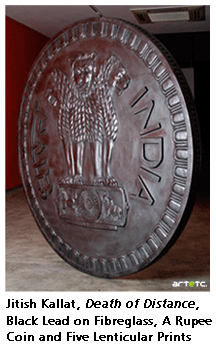

To take another Indian artist into consideration, we see the exemplary example of history and culture influencing art to bring forth a protesting idea as that of Jitish Kallat. Based on the famous Gandhi speech just prior to the historic Dandi March, where Gandhi called for civil disobedience against the Salt Act instituted by the British, Gandhi laid out that conduct be one of non-violence and complete peace. Kallat, almost disturbed by the change which has taken place in society, in his installation, reinvokes this speech which was forgotten in the passage of time. He reconstructs the whole speech using 4500 bones shaped alphabets as a plea for peace and a reminder of the violence currently prevailing in our societies - Kallat recalls the bloodshed, the worst since Indian Independence in Gujarat, close to where the Dandi speech was delivered. He says that his Public Notice series came from the chaos he has been witnessing in a disturbed world, explaining that answers to these fears may be found in the words once delivered as speeches by great men of our country. In Public Notice 3, he recreated the speech by Swami Vivekananda at the first Parliament of Religions in 1893, and was installed at every site the speech was delivered (today the Art Institute of Chicago). Kallat's works are very deeply moulded by Mumbai, the city he was born and lives in. In numerous ways, he has through his works. Brought to focus existences in the world today which are partial and disturbing. In his Death of Distance for example, he showcases the reality that exists so blatantly of the piercing disparity between the rich and the poor, and the continuous struggle which exists between them. The concept of his work is closely related to two incidents one, where the one rupee coin could connect [via the telephone] the entire nation to which a minister stated that it was the 'death of distance'. The other incident was when a school girl committed suicide when her mother could not give her a coin for a school-meal. Kallat's work questions the very crux upon which our society rests. And so we continue to see the mind of the artist and how he throws attention on everyday facts otherwise easily ignored he recognizes his environment and his country and chooses to protest that which dampens. Like in The Cry of the Gland, shirt pockets of commuters sag under the weight of everyday necessities like pens, wallets and cigarettes. Significantly, his works recognize this layering of society and uses metaphors to explain his ideas.

To take another Indian artist into consideration, we see the exemplary example of history and culture influencing art to bring forth a protesting idea as that of Jitish Kallat. Based on the famous Gandhi speech just prior to the historic Dandi March, where Gandhi called for civil disobedience against the Salt Act instituted by the British, Gandhi laid out that conduct be one of non-violence and complete peace. Kallat, almost disturbed by the change which has taken place in society, in his installation, reinvokes this speech which was forgotten in the passage of time. He reconstructs the whole speech using 4500 bones shaped alphabets as a plea for peace and a reminder of the violence currently prevailing in our societies - Kallat recalls the bloodshed, the worst since Indian Independence in Gujarat, close to where the Dandi speech was delivered. He says that his Public Notice series came from the chaos he has been witnessing in a disturbed world, explaining that answers to these fears may be found in the words once delivered as speeches by great men of our country. In Public Notice 3, he recreated the speech by Swami Vivekananda at the first Parliament of Religions in 1893, and was installed at every site the speech was delivered (today the Art Institute of Chicago). Kallat's works are very deeply moulded by Mumbai, the city he was born and lives in. In numerous ways, he has through his works. Brought to focus existences in the world today which are partial and disturbing. In his Death of Distance for example, he showcases the reality that exists so blatantly of the piercing disparity between the rich and the poor, and the continuous struggle which exists between them. The concept of his work is closely related to two incidents one, where the one rupee coin could connect [via the telephone] the entire nation to which a minister stated that it was the 'death of distance'. The other incident was when a school girl committed suicide when her mother could not give her a coin for a school-meal. Kallat's work questions the very crux upon which our society rests. And so we continue to see the mind of the artist and how he throws attention on everyday facts otherwise easily ignored he recognizes his environment and his country and chooses to protest that which dampens. Like in The Cry of the Gland, shirt pockets of commuters sag under the weight of everyday necessities like pens, wallets and cigarettes. Significantly, his works recognize this layering of society and uses metaphors to explain his ideas.

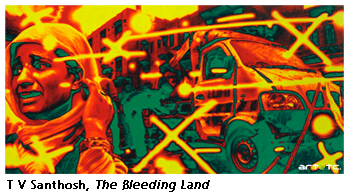

T V Santhosh's works have been, for a long while, an expression of him and how he has perceived the world around him. From his sculptures which carry a historical angle, to his paintings which consider the implications of political news and the media. Both are connected to each other and there exists, as Santhosh says, a dialogue between them. He goes back in history and explores the effects that violence and terror have had on society, and then continues to depict them using not only metaphors but by presenting them within lives of people. He looks deep into the effects of progress and then again the idea of nationhood and the enemy how perverted a thought pattern can become, affecting the very core of a nation. His works such as For a Life Lost Between Bullets and Bombs (oil on canvas, 48'x144') shows a man in obedience, saluting whose life is thrust in between bullets and bombs. Santhosh questions the meaning of life; he goes deep into the human. At first it seems like sympathy then apathy, then a very vehement protest. He continues this idea in The Bleeding Land (oil on canvas, 48'x96') as the terror on the face of a feeing woman captures the centre of his canvas set against a war torn land.

T V Santhosh's works have been, for a long while, an expression of him and how he has perceived the world around him. From his sculptures which carry a historical angle, to his paintings which consider the implications of political news and the media. Both are connected to each other and there exists, as Santhosh says, a dialogue between them. He goes back in history and explores the effects that violence and terror have had on society, and then continues to depict them using not only metaphors but by presenting them within lives of people. He looks deep into the effects of progress and then again the idea of nationhood and the enemy how perverted a thought pattern can become, affecting the very core of a nation. His works such as For a Life Lost Between Bullets and Bombs (oil on canvas, 48'x144') shows a man in obedience, saluting whose life is thrust in between bullets and bombs. Santhosh questions the meaning of life; he goes deep into the human. At first it seems like sympathy then apathy, then a very vehement protest. He continues this idea in The Bleeding Land (oil on canvas, 48'x96') as the terror on the face of a feeing woman captures the centre of his canvas set against a war torn land.

He carries hope in his works as well- the hope of men and women, not just terror stricken human beings, but his works tell of people who want to live, who desire to live whole and fulfilling lives. Interestingly, he has depicted this in his work titled The Advent of a Saviour, which he says, is the image of a pregnant woman taking a sonogram from a news report about Afghanistan. Resembling Mary, the mother of Christ, his work brings forward the hope that her unborn child could be a saviour. It links the various heroes of the world together, and the need for a saviour to save from extreme situations of violence and war.

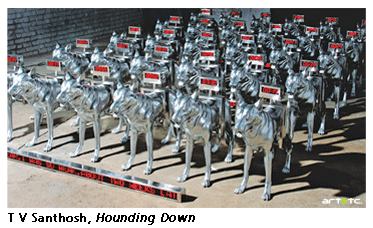

Santhosh is very unapologetic of the violence and disharmony that takes place in the world, he bares open the truth without masking it, also being blatantly critical. He goes into the very nature of our global world and uses everyday media news in such a way which is intriguing, questioning and open. And thus by using solarised colour schemes he gives the impression of photographic negatives, he adds his thinking into each work of is, where paintings depict not only the terror involved but so also deep thoughts associated with terror of the other side which is forgotten. Of freedom, democracy and the right to peace. A globalised world is torn open, the insides of which are thrown before the viewer using symbols and meanings. In his Hounding Down, the installation of thirty stainless steel dogs, each with a digital timer strapped to its back, represent the dogs of violence and war. Santhosh speaks of fanaticism, of fascist world moving towards an end. In a way, the artist uses current situations to become prophetic in his speaking. So when the Mumbai terror attacks took place, his works which deal with the subject were a prelude to the event in many ways. His works are often multidimensional in meaning, in this one for example, dogs speak about life and movement. The bombs mean destruction and tied to the dogs, Santhosh recalls when dogs were used during World War II as suicide bomb squads. And today, bomb squads use dogs to locate bombs.

Santhosh is very unapologetic of the violence and disharmony that takes place in the world, he bares open the truth without masking it, also being blatantly critical. He goes into the very nature of our global world and uses everyday media news in such a way which is intriguing, questioning and open. And thus by using solarised colour schemes he gives the impression of photographic negatives, he adds his thinking into each work of is, where paintings depict not only the terror involved but so also deep thoughts associated with terror of the other side which is forgotten. Of freedom, democracy and the right to peace. A globalised world is torn open, the insides of which are thrown before the viewer using symbols and meanings. In his Hounding Down, the installation of thirty stainless steel dogs, each with a digital timer strapped to its back, represent the dogs of violence and war. Santhosh speaks of fanaticism, of fascist world moving towards an end. In a way, the artist uses current situations to become prophetic in his speaking. So when the Mumbai terror attacks took place, his works which deal with the subject were a prelude to the event in many ways. His works are often multidimensional in meaning, in this one for example, dogs speak about life and movement. The bombs mean destruction and tied to the dogs, Santhosh recalls when dogs were used during World War II as suicide bomb squads. And today, bomb squads use dogs to locate bombs.

Santhosh's expression of the complexities of life is vivid, and somewhere there is hidden the element of healing. It, when dwelt deep, can be recognized. In his installation, A Room to Pray, the title itself shares the notion of the need for peace in a turbulent world.

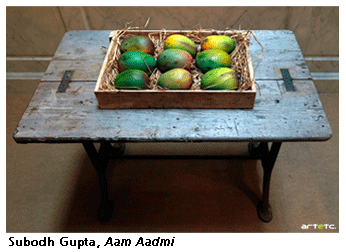

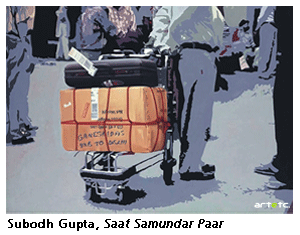

Subodh Gupta is yet another famed artist who speaks of change and the economic movement of India and the world through his installations. Using everyday objects, so close to the ordinary man [the artist says to him as well, things one grows up using] he links the intimacy intended to the effects of change, which ultimately moves to a materialistic mind-set. In his work titled Line of Control, a huge mushroom cloud of pots and pans, where he highlights the issues dealing with the contested Kashmir border between India and Pakistan, and what this could lead to in terms of an economic disaster. Here, he projects an atomic blast out of everyday objects used by men and women. The title tells the viewer of the idea and the installation itself is a metaphor that explains it. In his Saat Samunder Paar (Across the Seven Seas) where baggage trolleys used in airports are depicted to explain change that comes from migration and movement change which effects histories and the lives of peoples across the world. Here, a personal connect can be recognized as Subodh tells of the migrations from India. In another work, the use of cow-dung which tells of rural India (the use of it to clean and the association of purity and spirituality associated with it) is washed off in his video work titled Detergent where the artist tries to was away the dirt on his body from all this dung. It again, like many of his works have meanings which are complex and layered of India, of his life and the lives of many which are intertwined by many, many intricacies both social and spiritual. These layers of meanings can be recognized as we traverse his works, from Take off Your Shoes and Wash Your Hands and Common Man. And so also Aam Admi, an installation where the mango grown all over the world, is the fruit of the common man.

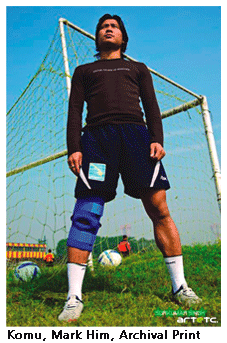

Lastly, Riyas Komu's works, both paintings and installations, are perfect examples of how an artist and his works extend to the environment in which they exist. He connects humans and their destinies to the political, social and religious systems which exist. He uses these as the framework, which provides the opportunity for his viewers to decipher and find layers of meanings in his work that gradually reveals the multi-dimensional existence arising from an ideology. This he connects to the ''human''. In his work titled Watching the World Spirits from the Gardens of Babylon, a wooden wagon with a canon and a carved brain, invites viewers to look closely at the damage involved as he highlights the US invasions of Iraq and the impact on the individual. So also, in his Left Leg series, we see large human left legs of football players in steel, wood and concrete, where not only is the artist's love for the game highlighted but about the children of the streets of Baghdad ( and their love to play) as victims to bombings. Riyas explains that art is a way to express socially, where he uses photographic references from media, where politics seem to loom large. Riyas moves to other mediums as well documentaries and photography. The eight minute documentary involved the streets and roadside restaurants of Mumbai (titled The Politics of Nostalgia and Food). And in his solo exhibition Mark Him, the intent was to recognize the place of footballers in society.

Lastly, Riyas Komu's works, both paintings and installations, are perfect examples of how an artist and his works extend to the environment in which they exist. He connects humans and their destinies to the political, social and religious systems which exist. He uses these as the framework, which provides the opportunity for his viewers to decipher and find layers of meanings in his work that gradually reveals the multi-dimensional existence arising from an ideology. This he connects to the ''human''. In his work titled Watching the World Spirits from the Gardens of Babylon, a wooden wagon with a canon and a carved brain, invites viewers to look closely at the damage involved as he highlights the US invasions of Iraq and the impact on the individual. So also, in his Left Leg series, we see large human left legs of football players in steel, wood and concrete, where not only is the artist's love for the game highlighted but about the children of the streets of Baghdad ( and their love to play) as victims to bombings. Riyas explains that art is a way to express socially, where he uses photographic references from media, where politics seem to loom large. Riyas moves to other mediums as well documentaries and photography. The eight minute documentary involved the streets and roadside restaurants of Mumbai (titled The Politics of Nostalgia and Food). And in his solo exhibition Mark Him, the intent was to recognize the place of footballers in society.

Riyas explains that art is also a means to solidarity. When his work titled Speak Up was accepted open heartedly as he emphasised his views on the issues of North Eastern India, 'people felt a certain oneness with it, especially that an artist from Mumbai was expressing their concern'. Using microphones as the main subject in his work, Riyas says it was to represent unheard voices- so welcoming was he that the public supported him in his work, 'and children wanted me to paint the walls of their rooms.' Riyas explains that this is what art can do, that it can build easily what other mediums often struggle to do. As a medium which is visually appealing and one which lures rather than scatters, Riya's work is a fine example.

Like these artists, there are many others who have chosen to express through art. The web of life dictated by numerous conditions and that which comes forth from it, are objected to from a personal point of view. But what is important is that, although these maybe personal in nature, it evokes the needed reaction in viewers. Perhaps subtly at first, but eventually it is a wheel that gathers reactions as it moves. And it is only time before art is used widely in India to speak up.