- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

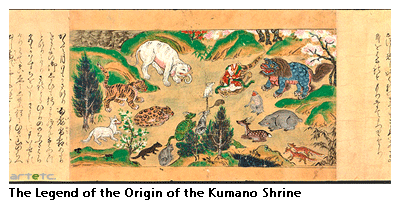

The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

New York. Featuring works of art in a range of mediums and formats, the exhibition, Storytelling in Japanese Art explores myriad subjects that have preoccupied the Japanese imagination for centuries Buddhist and Shinto miracle tales; the romantic adventures of legendary heroes and their feats at times of war; animals and fantastical creatures that cavort within the human realm; and the ghoulish antics of ghosts and monsters, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Displaying more than sixty works from the endlessly fascinating world of Japanese storytelling, the exhibition started on November 19, 2011 and continues till May 6, 2012. The exhibition is made possible by The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation with additional support provided by the Japan Foundation.

Japan has a long and rich history of pairing narrative texts with elaborate illustrations a tradition that continues to this day with manga and other popular forms of animation. From illustrated books and folding screens to textiles and even playing cards, the objects on view, which date from the twelfth to the nineteenth century, vividly capture the life and spirit of their time. The illustrated handscroll, or emaki, a narrative format is also displayed and it is essential not only to the dissemination of Japanese tales but also to the very ways in which it is crafted. The more than twenty handscrolls on view in the galleries demonstrate the many ways in which the pictorial space of the emaki is designed to draw viewers directly into a story, offering a rare opportunity for visitors to experience the pleasures and intellectual challenges inherent in Japanese narrative painting.

Japan has a long and rich history of pairing narrative texts with elaborate illustrations a tradition that continues to this day with manga and other popular forms of animation. From illustrated books and folding screens to textiles and even playing cards, the objects on view, which date from the twelfth to the nineteenth century, vividly capture the life and spirit of their time. The illustrated handscroll, or emaki, a narrative format is also displayed and it is essential not only to the dissemination of Japanese tales but also to the very ways in which it is crafted. The more than twenty handscrolls on view in the galleries demonstrate the many ways in which the pictorial space of the emaki is designed to draw viewers directly into a story, offering a rare opportunity for visitors to experience the pleasures and intellectual challenges inherent in Japanese narrative painting.

Contributing significantly to the development and dissemination of otogi zoshi was the handscroll, a major vehicle for painting and writing throughout East Asia. Illustrated handscrolls, or emaki (picture scrolls), first emerged in Japan in the eighth century. They generally measure about one foot high and can extend for more than thirty feet. Emaki are meant to be unrolled laterally, from right to left, and read in sequential segments of about two feet each. Usually, text sections are interspersed with images, with the narrative preceding the related illustration. A scroll is unrolled with the left hand, while the right hand rolls the part already viewed, allowing the story to emerge from the left and disappear to the right. With the freedom to move through the scenes at his or her own pace, the viewer physically experiences the progression of time and space as the past is rolled away, the present is slowly uncovered, and the future waits to be seen.

Japanese storytelling reached its apogee during the Nanbokucho and Muromachi periods (1336-1573). The more than four hundred tales that emerged during the Muromachi period are known collectively as otogi zoshi. Ranging widely in theme, from religious parables to capricious fables, these short, often didactic stories are a world apart from the courtly romantic tales of the Heian period (794-1185). Many of the plots stem from the epics of the Kamakura period (1185-1333), a time of marked military ascendancy and the rise of a powerful warrior class.