- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

In-between Protest and Art

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Chhatrapati Dutta

Sighting I

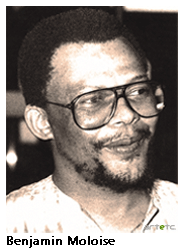

“I am proud to be what I am…

The storm of oppression will be followed

By the rain of my blood

I am proud to give my life

My one solitary life.”

-Benjamin Moloise (1985)

These lines of poetry by Benjamin Moloise were penned before he was executed by hanging during the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa by the hard-line government of P. W. Botha on October 18, 1985. No amount of international resistance, including that of USA and the USSR could persuade the apartheid state to prevent the controversial conviction to save his life. One among the black majority who were long treated as second-class citizens in their own land; Moloise was a factory worker, member of the then banned African National Congress and a poet. In the context of violent resistance to apartheid in South Africa's black townships, attacks on black officials and police officers who administered state authority were common. Convicted in a plot to kill a black police officer in 1983, his execution further escalated the existing racial violence against the furious black rioting protesters, that inversely grew into a mass movement throughout the small townships. Benjamin's last lines spread by word of mouth like wild fire vindicating Moloise's final message, and subsequently became a catalyst at anti-apartheid rallies.

These lines of poetry by Benjamin Moloise were penned before he was executed by hanging during the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa by the hard-line government of P. W. Botha on October 18, 1985. No amount of international resistance, including that of USA and the USSR could persuade the apartheid state to prevent the controversial conviction to save his life. One among the black majority who were long treated as second-class citizens in their own land; Moloise was a factory worker, member of the then banned African National Congress and a poet. In the context of violent resistance to apartheid in South Africa's black townships, attacks on black officials and police officers who administered state authority were common. Convicted in a plot to kill a black police officer in 1983, his execution further escalated the existing racial violence against the furious black rioting protesters, that inversely grew into a mass movement throughout the small townships. Benjamin's last lines spread by word of mouth like wild fire vindicating Moloise's final message, and subsequently became a catalyst at anti-apartheid rallies.

Though the vestiges of apartheid still shape South African politics and society, the negotiations to end apartheid led to democratic elections in 1994 and were won by the ANC, under Nelson Mandela.

Sighting II

“Arise, ye workers from your slumber,

Arise, ye prisoners of want.

For reason in revolt now thunders,

and at last ends the age of cant!

Away with all your superstitions,

Servile masses, arise, arise!

We'll change henceforth the old

tradition,

And spurn the dust to win the prize!

So comrades, come rally,

And the last fight let us face.

The Internationale,

Unites the human race.

So comrades, come rally,

And the last fight let us face.

The Internationale,

Unites the human race.”

-Eugene Pottier (1871)

Eugene Pottier, the author of the worlds most sung proletariat song was a French revolutionary socialist, poet and transport worker.

Eugene Pottier, the author of the worlds most sung proletariat song was a French revolutionary socialist, poet and transport worker.

“This song has been translated into all European and other languages. In whatever country a class-conscious worker finds himself, wherever fate may cast him, however much he may feel himself a stranger, without language, without friends, far from his native country - he can find himself comrades and friends by the familiar refrain of the Internationale.”

“The workers of all countries have adopted the song of their foremost fighter, the proletarian poet, and have made it the world-wide song of the proletariat.”

“And so the workers of all countries now honour the memory of Eugène Pottier. His wife and daughter are still alive and living in poverty, as the author of the Internationale lived all his life. He was born in Paris on October 4, 1816. He was 14 when he composed his first song, and it was called: Long Live Liberty! In 1848 he was a fighter on the barricades in the workers' great battle against the bourgeoisie.”

“Pottier was born into a poor family, and all his life remained a poor man, a proletarian, earning his bread as a packer and later by tracing patterns on fabrics.”

“From 1840 onwards, he responded to all great events in the life of France with militant songs, awakening the consciousness of the backward, calling on the workers to unite, castigating the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois governments of France.”

“In the days of the great Paris Commune (1871), Pottier was elected a member. Of the 3,600 votes cast, he received 3,352. He took part in all the activities of the Commune, that first proletarian government.”

– V. I. Lenin. 1913.

The Paris Commune was mercilessly crushed in May 1871. Pottier's pen flowed in exile, on the next day, so to speak, in June 1871, creating one of the most legendary hymns dedicated to the revolution.

Sighting III

Hei samalo, hei samalo, Hei samalo,

hei samalo,

Hei samalo dhaan ho,

Kastey-ta dao shaan ho,

Jaan kobul aar maan kobul,

Aar debona, aar daebona roktey bona

dhaan, moder praan ho.

Chini tomay chini go,

Jaani tomaay jaani go,

Shaada haatir kaala mahut tumi naa!

Ponchash laakh praan disi,

Maa bon-a-der maan disi,

Kaalo bazar aala koro tumi naa!

Mora tulbona dhaan porer golay,

Morbona aar khudaar zaalay

morbonaa.

Jaar jomi se laangol chaalay,

Dher shoechhi, aar toh mora shoibo

naa.

Ebaar laangol dhora korha haataer

shopoth bhulonaa.

Jaan kobul aar maan kobul,Aar debona, aar daebona roktey bona

dhaan, moder praan ho.

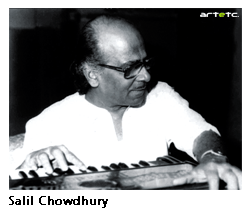

-Salil Chowdhury

The grand aura of Salil Chowdhury the famous poet, composer, singer, musician, et al eclipses the early years of his calling. Having been exposed to the growing peasant movement in 1945 in Tebhaga, he soon became an active member of the Indian Peoples Theater Association, the cultural wing of the Communist Party which he also joined thereafter.

The grand aura of Salil Chowdhury the famous poet, composer, singer, musician, et al eclipses the early years of his calling. Having been exposed to the growing peasant movement in 1945 in Tebhaga, he soon became an active member of the Indian Peoples Theater Association, the cultural wing of the Communist Party which he also joined thereafter.

The demand of the sharecroppers of Bengal for two-thirds of their own produce from land belonging to the moneyed gentry spread violently through the fields of Tebhaga - marking a turning point in the history of politicised agrarian movements in India. It extended into post- independent India, and the Tebhaga movement left its lessons for others who became part of land struggle movements of the future.

Soon a flag bearer of the IPTA, Salil da, as he popularly came to be known as, painted breathtaking pictures with his lyrics dwelling on the sweat and bloodshed of the peasantry and the plight of the common man, in general, in his songs. The theatrical performances revolved around themes of British imperialism, social inequalities and the growing freedom struggle, often all clubbed into one. Moving from village to village singing and performing standing hand in hand with the agitating cultivators to inspire and elevate their political consciousness and revolutionary spirit.

The strong political influence he had on the masses made him a potential threat for the British, forcing Salil Chowdhury to go underground for four years. His fight for justice through his music continued well into the independent era, an example of which is the song above.

Deduction

The three instances of individual voices sighted - arising amidst larger social and political happenings and reaching out into the public domain - could lead to an abstract of modus operandi common to all arts. Though every individual has a right to free expression, addressing issues beyond individual idiosyncrasies, inevitably involves conviction and purpose. But in the same breath, it is absolutely legitimate to question whether conviction alone can create great works of art. The three authors were not only directly involved in the struggle they addressed; they had to endure great hardship and suffered sacrifices to the extent of facing death to stand by it. But inspite of the adversities, their works go beyond the temporal. They had belief in a cause and a deep understanding of its ramifications both at the individual and social levels, and the privations gave them an added edge. They were enriched with sensitivity and compassion and might of the mind; which left indelible imprints on their creative outputs. Then again, does a purpose rather than the personal need for simple self expression within the individual helps to reach greater creative heights compared to the idiosyncratic, the wild and the romantic?

The three instances of individual voices sighted - arising amidst larger social and political happenings and reaching out into the public domain - could lead to an abstract of modus operandi common to all arts. Though every individual has a right to free expression, addressing issues beyond individual idiosyncrasies, inevitably involves conviction and purpose. But in the same breath, it is absolutely legitimate to question whether conviction alone can create great works of art. The three authors were not only directly involved in the struggle they addressed; they had to endure great hardship and suffered sacrifices to the extent of facing death to stand by it. But inspite of the adversities, their works go beyond the temporal. They had belief in a cause and a deep understanding of its ramifications both at the individual and social levels, and the privations gave them an added edge. They were enriched with sensitivity and compassion and might of the mind; which left indelible imprints on their creative outputs. Then again, does a purpose rather than the personal need for simple self expression within the individual helps to reach greater creative heights compared to the idiosyncratic, the wild and the romantic?

Though piles of works of literature, art and poetry are created during and after such times of suppression, with insecurity and fear as companions on one side and great strength, conviction and will on the other, few survive. This however does not take away the significance of the lesser works of the time. For it is always because of the profusion that the individual stands out. Of circumstantial importance are also the infrastructure group / organization / party - that stand behind the propagation and popularity of the works. After all, of what importance would a potential weapon be, if it is left lying in the scabbard? Eloquent works are withering away in remote corners even today when reaching out to the masses - especially at times of protest - is the prime objective, failing which, even a powerful work is lost invain. It is a rarity to find resurrected works getting reinstated with its deserved glory, except, possibly in the case of visual arts. But for those works that get recognition during its own time - it's another story.

After one and half a century of the Paris Commune, Eugene Pottier's International still spreads its message throughout the world, making him more alive than ever before. However successful or futile the Tebhaga and Telengana movements were, some path breaking art, music and literature were born out of its painful wombs. Salil Chowdhury's songs, sung so frequently even today, make our hearts skip a beat. And, however meaningful and successful South African democracy might have turned out to be, Benjamin Moloise will remain to be one of the most revered revolutionary poets of his time. Such poets, singers and artists continue to live among us; not because of the brutal dilution of the Paris Commune, or the implementation of the Bargadari Act, that finally came about due to the fall-outs of the Tebhaga uprising. Nor are the African works remembered only because we are ashamed of apartheid; it is because of the sheer power of a piece of art that it can endure Time.

After one and half a century of the Paris Commune, Eugene Pottier's International still spreads its message throughout the world, making him more alive than ever before. However successful or futile the Tebhaga and Telengana movements were, some path breaking art, music and literature were born out of its painful wombs. Salil Chowdhury's songs, sung so frequently even today, make our hearts skip a beat. And, however meaningful and successful South African democracy might have turned out to be, Benjamin Moloise will remain to be one of the most revered revolutionary poets of his time. Such poets, singers and artists continue to live among us; not because of the brutal dilution of the Paris Commune, or the implementation of the Bargadari Act, that finally came about due to the fall-outs of the Tebhaga uprising. Nor are the African works remembered only because we are ashamed of apartheid; it is because of the sheer power of a piece of art that it can endure Time.

Having said that, does one then accept the notion that there is no truth greater than that of Art? If yes, then how should one address matters of social commitment and conviction of an artist? Since such matters are never reciprocated by success or recognition in any form, how does one evaluate the contribution of such artists and their works in the 'market' driven system?

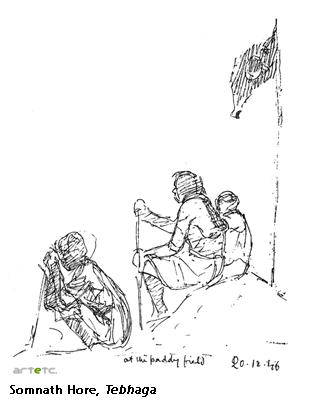

Instance IV

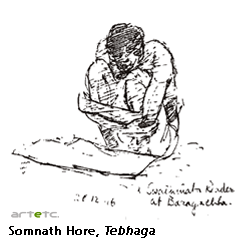

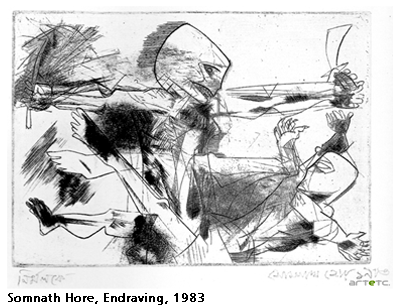

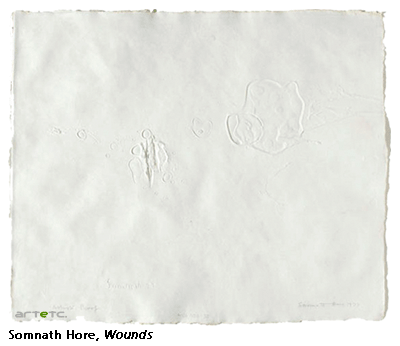

From the days of the Tebhaga Diary of 1946 until he breathed his last in 2006, Somnath Hore's colossal repertoire of drawings, paintings, prints and sculptures never delineated protest per say. What he rather did throughout his life was to reflect the misery and sad plight of the destitute and broken.

From the days of the Tebhaga Diary of 1946 until he breathed his last in 2006, Somnath Hore's colossal repertoire of drawings, paintings, prints and sculptures never delineated protest per say. What he rather did throughout his life was to reflect the misery and sad plight of the destitute and broken.

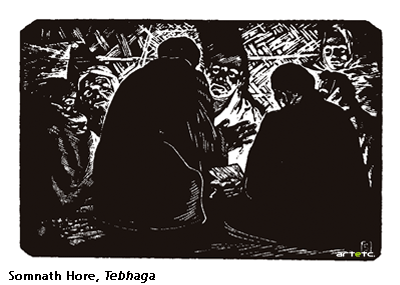

Introducing the Tebhaga - An Artists Diary and Sketchbook published in 1990 Samik Bandopadhayay encapsulates Hore's greater engagement.

“…Hore persisted with a dogged determination in his penetration of a reality which he defines in terms of man's inhumanity to man, power riding roughshod over people…. To penetrate into that reality, Hore had set up for himself the barriers of material which he has to break into (like wood at first, and then paper pulp for the first Wounds) or moulds, as with bronze (which is now his material for his new Wounds). Hore's vision of wounds bears within it the experience of the Tebhaga movement and the way it has receded into the past and memory, leaving only the impression of an enormous wound, a wound created by a kind of betrayal, which is not just political but moral in the deepest sense. Hore has traveled a long way from those early, sunny sketches of a rural community in its first flush of a sense of power and achievement; to his darker evocations of the same experience, now already irretrievably lost, in the wood engravings; to the white paper pierced with a knife or the metal with gaping wounds in all their pain and horror”.

Inspite of his early reliance on his senior contemporary Chittaprasad, it is evident that Somnath Hore came to believe and practice in something more in the lines of what Georg Grosz writes in the twenties.

“Go to a proletarian meeting; look and listen… And understand these masses are the ones who are reorganizing the world. Not you! But you can work with them. You can help them if you want to! And that way you can give your art a content which was supported by the revolutionary ideas of the workers.”

Hore luckily had revered people like Nripen Chakroborty and Somnath Lahiri - who echoed Grosz's for him during his early Art College days and whom he met due to his political affiliation to the Communist Party. “If you want to have a look at the Tebhaga movement, go to Rangpur”.

As a young student of the Government Art College, the politically charged Somnath Hore left Calcutta for Rangpur in North Bengal, on the night of 17 December 1946, to document and be witness to the first consciously - attempted revolt by a politicized peasantry in Indian history.

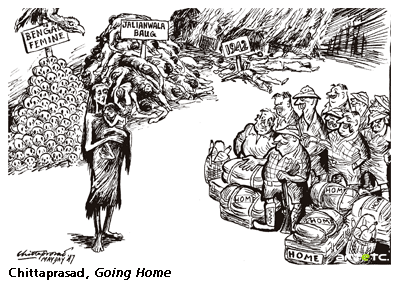

Be it coincidental or out of a young artist's admiration and consequent influence, there is a similarity in structure and pattern of observation that pour in as text of the Tebhaga Diary to that of Chittaprasad's tour through the famine ridden Medinipore districts in November 1943. But where Hore consciously deviates from his senior is in the way he divulges his figures. With no attempt to dramatize or distort the surrounding reality, scenes of harvesting peasants, and secret meetings in the silence of the night or someone reading the 'Swadhinata' are all matter of fact and unhindered. Instead of the brush - which Chittaprasad had mastery in Hore worked with the pen nib and ink. The starkness of his line shows no sign of emotion. Like a line etched mirror, Hore's documentary drawings of the mobilization of the Tebhaga peasants and his comrades are brought down to the essential minimum. The uniformity of the dimension of the lines leaves no scope for emphasis. Though one can never be sure if the famine of 1943 that Hore suffered and saw against the back ground of poverty-ridden Bengal as an adolescent- the memories of which he carried with him-throughout his life like a shadow that preceded him - is responsible for the economy of his leaner renderings.

Be it coincidental or out of a young artist's admiration and consequent influence, there is a similarity in structure and pattern of observation that pour in as text of the Tebhaga Diary to that of Chittaprasad's tour through the famine ridden Medinipore districts in November 1943. But where Hore consciously deviates from his senior is in the way he divulges his figures. With no attempt to dramatize or distort the surrounding reality, scenes of harvesting peasants, and secret meetings in the silence of the night or someone reading the 'Swadhinata' are all matter of fact and unhindered. Instead of the brush - which Chittaprasad had mastery in Hore worked with the pen nib and ink. The starkness of his line shows no sign of emotion. Like a line etched mirror, Hore's documentary drawings of the mobilization of the Tebhaga peasants and his comrades are brought down to the essential minimum. The uniformity of the dimension of the lines leaves no scope for emphasis. Though one can never be sure if the famine of 1943 that Hore suffered and saw against the back ground of poverty-ridden Bengal as an adolescent- the memories of which he carried with him-throughout his life like a shadow that preceded him - is responsible for the economy of his leaner renderings.

But he certainly “…. goes over and over this obsessively. In everything he sees, he reads its gesture of poverty. So in a crack in the earth, he sees a dire menace. In fissures in the wall, he recalls a gaping wound. Even his sensuous fantasies are sewn up in a skin of suffering. Lean bodies of men and women huddled in wan despair. With faces whose flesh sinks into the bone; whose chests cannot find enough skin to hide their hollow nakedness; whose eyes are sockets from which all light has been drained out; mouths whose only voice is that of rattling teeth. Then the skinny dogs and bony cows and goats that keep them languid company.”

“They do not repel our eye; they draw us in. His artistry gives each item its kind of appeal; the sharpness of the bone, the tightness of the skin, the deadness of eyes, the muteness of mouths, the limp inertia of the folded body. They entice the eye in and lacerate it. Blood-shot, it seeks a world behind the world of flowering hedges.”

“They do not repel our eye; they draw us in. His artistry gives each item its kind of appeal; the sharpness of the bone, the tightness of the skin, the deadness of eyes, the muteness of mouths, the limp inertia of the folded body. They entice the eye in and lacerate it. Blood-shot, it seeks a world behind the world of flowering hedges.”

“There are loud pictures of suffering whose message passes over our heads like barked out slogans. Somnath's are different. They are insidious; they slip slowly in. Then they disturb us and shade into the didactic. We start thinking, what is this world that we see daily? And run our hands over our faces. And find that the bone lies below the flesh.” -K. G. Subramanyan.

Irrespective of his success and true to his essential self, Somnath Hore repeatedly rebuilt on his faith and conviction of standing by his fellowmen. Sharpening each chosen tool with his indomitable spirit, he spoke of the pain they suffered - each time - creating works that cut deep through the flab of our flesh to reach into the conscience of the bone. Even though he walked hand in hand with the revolutionary spirit of the masses, their portrayal is marked by the silence of their suffering, their voices lost in the depth of the naval before they reach the elevation of the voice box.

Irrespective of his success and true to his essential self, Somnath Hore repeatedly rebuilt on his faith and conviction of standing by his fellowmen. Sharpening each chosen tool with his indomitable spirit, he spoke of the pain they suffered - each time - creating works that cut deep through the flab of our flesh to reach into the conscience of the bone. Even though he walked hand in hand with the revolutionary spirit of the masses, their portrayal is marked by the silence of their suffering, their voices lost in the depth of the naval before they reach the elevation of the voice box.

The vocal silence of his images becomes testimonials of a time that provoke the spirit of protest in us. His works are potential tools without the obvious edge. They slit the nerves of complacence without drawing blood. They penetrate to the depths of our consciousness.