- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

State Britain: Mark Wallinger

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Sabrina Osborne

Brian Haw began his peace protest at his mini camp in June, 2001, opposite The Houses of Parliament, London. He protested tirelessly for years against Tony Blair and the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq. The placards declared "You Lie Kids Die BLIAR" and "Christ Is Risen Indeed!". There were also Road spattered appeals to motorists to "Beep for Brian". On May 23, 2006, his camp was demolished and his belongings removed, following the passing of the Serious Organized Crime and Police Act forbidding unauthorized demonstrations within a kilometre of Parliament Square.

Brian Haw began his peace protest at his mini camp in June, 2001, opposite The Houses of Parliament, London. He protested tirelessly for years against Tony Blair and the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq. The placards declared "You Lie Kids Die BLIAR" and "Christ Is Risen Indeed!". There were also Road spattered appeals to motorists to "Beep for Brian". On May 23, 2006, his camp was demolished and his belongings removed, following the passing of the Serious Organized Crime and Police Act forbidding unauthorized demonstrations within a kilometre of Parliament Square.

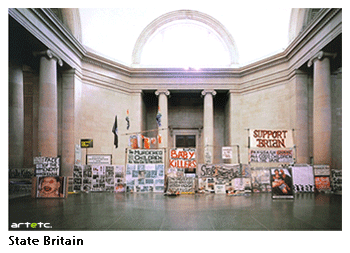

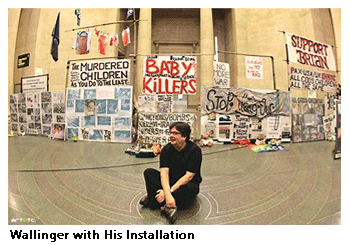

In south east London's Old Kent Road studio, fourteen people worked for six months to recreate some 600 tattered banners, placards and posters denouncing Tony Blair and George Bush as mass murderers over the Iraq war. It cost Mark Wallinger £90,000, which won him the £25,000 prestigious Turner Prize in 2007. The exclusion zone, taken literally, bisected Tate Britain, and part of State Britain fell within its border.

The overtly political work, State Britain, was shown at the Duveen galleries at Tate Britain, London. Wallinger remade 40 metre long replica of Haw's peace camp in every detail: complete with the tarpaulin shelter, tea-making area to banners, flags, photos and posters and hand painted placards, rickety knocked-together information boards, handmade signs, photocopied war zone reports, a group of dolls in Victorian dresses lying beside a plastic baby with missing arms and legs bloodied with paint, mutilated soft toys, teddy bears saying "too much to bear", soft toys piled in a paper coffin, commemorative crosses and satirical slogans like, "Pensioners want a slice of the cake, not crumbs”, amassed by Haw and his supporters, the accumulation of about five-year tenure. The cumulative recreation of a space inhabited by this individual with all his stuff complete with Tesco biscuits, sleeping bag, tobacco and water bottles, added this smell of intense sentimental value. In a way it became a continuation of the protest, simultaneously mocking a law designed to curtail the freedom to protest. Bringing the protest inside an institution provided the chance almost to freeze it, presenting it as a simulacrum of itself.

The overtly political work, State Britain, was shown at the Duveen galleries at Tate Britain, London. Wallinger remade 40 metre long replica of Haw's peace camp in every detail: complete with the tarpaulin shelter, tea-making area to banners, flags, photos and posters and hand painted placards, rickety knocked-together information boards, handmade signs, photocopied war zone reports, a group of dolls in Victorian dresses lying beside a plastic baby with missing arms and legs bloodied with paint, mutilated soft toys, teddy bears saying "too much to bear", soft toys piled in a paper coffin, commemorative crosses and satirical slogans like, "Pensioners want a slice of the cake, not crumbs”, amassed by Haw and his supporters, the accumulation of about five-year tenure. The cumulative recreation of a space inhabited by this individual with all his stuff complete with Tesco biscuits, sleeping bag, tobacco and water bottles, added this smell of intense sentimental value. In a way it became a continuation of the protest, simultaneously mocking a law designed to curtail the freedom to protest. Bringing the protest inside an institution provided the chance almost to freeze it, presenting it as a simulacrum of itself.

Wallinger said, "I think it's regrettable that people have been so quiescent about what the Serious Organised Crime Act has done to people who want to demonstrate. It is against The Magna Carta, and that was produced in 1215, before democracy. It's important these freedoms are fought for and preserved." Wallinger also taped a line on the floor, indicating an arc of the kilometre cordon as it passes through the gallery. Creating its own resonances and echoes, the line placed the work in a conversation with the rest of Tate Britain.

The jury praised State Britain for "its immediacy, visceral intensity and historic importance". They went on: "The work combines a bold political statement with art's ability to articulate fundamental human truths."

"Brian Haw is a remarkable man who has waged a tireless campaign against the folly and hubris of our government's foreign policy. For six-and-a-half years he has remained steadfast in Parliament Square, the last dissenting voice in Britain. Bring home the troops, give us back our rights, trust the people," Wallinger said.

Talking to BBC News Entertainment, he revealed, “I started taking photographs of it and I thought it was an amazing document, really. Anyone who took the trouble to cross over the road and have a proper look would have been impressed by the intensity and the insight. Things started coming together as in May the police introduced new conditions on Brian's protest so it looked like his time might be short. So on 18 May I took hundreds of digital images of the whole process. I proposed making a replica to the Tate's curator on 22 May, and that very night police arrived to take it all away. So once that happened it seemed like a public service, almost, to recreate what the police had removed”. Englishness as a trope of identity, the events, individuals which build up a sense of national belonging, has been the very core of Wallinger's work. He said, "to make an art that connected with the world and with a public beyond a small esoteric coterie. I wanted to say something about how images are used to coerce or incentivise or whip up the best and the worst in people. But it couldn't be propaganda. I wasn't at Speakers' Corner or standing for election. It did have to be art".

Talking to BBC News Entertainment, he revealed, “I started taking photographs of it and I thought it was an amazing document, really. Anyone who took the trouble to cross over the road and have a proper look would have been impressed by the intensity and the insight. Things started coming together as in May the police introduced new conditions on Brian's protest so it looked like his time might be short. So on 18 May I took hundreds of digital images of the whole process. I proposed making a replica to the Tate's curator on 22 May, and that very night police arrived to take it all away. So once that happened it seemed like a public service, almost, to recreate what the police had removed”. Englishness as a trope of identity, the events, individuals which build up a sense of national belonging, has been the very core of Wallinger's work. He said, "to make an art that connected with the world and with a public beyond a small esoteric coterie. I wanted to say something about how images are used to coerce or incentivise or whip up the best and the worst in people. But it couldn't be propaganda. I wasn't at Speakers' Corner or standing for election. It did have to be art".

He felt that modern Britain exhibits a "timidity compared with previous generations about works in the public realm, that's part of the reason why Brian Haw's protest was so fascinating. I'd been following it for a couple of years and was very surprised that people weren't more up in arms about this exclusion zone that had been imposed. Not least about the stupidity of making a law essentially to get rid of Brian, just about the only person left in Britain still protesting about the war."

What was State Britain, a protest or an appropriation? It was an installation, an institutional critique, as well an example of relational aesthetics. It pushed the mores of recent installation art, "public" nature of institutional space such as Tate Britain's Duveen Galleries. The place and context, the very site specificity of the work made the viewer read the work in a different light.

A montage of writings taken from George Orwell and Thomas Jefferson, the journalist Henry Porter and Tony Blair himself, was presented in an accompanying exhibition publication - "When I pass protesters every day at Downing Street, and believe me, you name it, they protest against it, I may not like what they call me, but I thank God they can. That's called freedom".

Artists like Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren, Cildo Meireles, Allan Sekula, did make works as a critique to the institution which housed the work which on the other hand also displays the liberalism of the institution for still showing the work, defusing the intensity of the criticism in the work itself, as Susan Sontag argued. State Britain questioned the role of British institutions at a time of war, ever changing government dissents, freedom of expression, impotence of protest and for that matter standing of art as protest.

The “Observer” critic Laura Cumming wrote, “By bringing Haw's protest into the museum, into these marmoreal surroundings, Wallinger surrounds it with austere silence and space. It becomes an elegiac commemoration, tremendously poignant, of one man's campaign and hundreds of thousands of deaths. Except that in this case the war, and the protest, are still going on somewhere else as you walk”.

Ironically at the time of writing this article on 11th April 2012, Damien Hirst's famous sculpture Hymn placed outside Tate Modern, was graffited by Occupy London protesters, in an attempt to take action against the free market and, in this instance, its consequences on art. The article, by Kester Brewin, calls for artists to return to a creative process that is not about "wealth". Occupy London's website says that they are all set to strike back this May as people around the world take to the streets to mark one year since the indignados reclaimed their squares in Spain and Greece, and six months since the Occupy movement went global in late 2011.

Better known as 'Dancing Bear', Wallinger was born in Chigwell in 1959. He lives and works in London. He studied at Chelsea School of Art, London (1978-81) and Goldsmiths' College, London (1983-85). Since the mid-1980s Wallinger's primary concern has been to establish a valid critical approach to the 'politics of representation and the representation of politics' and has often explored issues of the responsibilities of individuals and those of society in his work. He was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1995 and won it in 2007. He represented Britain at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001.