- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

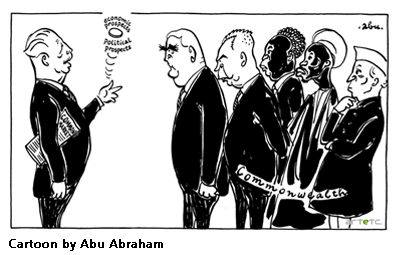

Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Sritama Halder

“Cartoonists have lived up to their reputation by proposing, preaching and pinching the leaders where it hurts the most.”

From Drawing the Battle Lines, A Collection of Cartoons Against Communalism, Sahmat

A political cartoon is a satire in lines that aims to comment on a nation's ruling system, the authorities, their power and policies in order to critique the political situations that potentially change the lives of numerous citizens. Behind the apparent humour of this genre a strong political consciousness operates. A political cartoonist a corrective agent to bring in a socio-political change functions as the voice of conscience of a whole nation. A cartoon does not offer to solve a problem but it rather draws the public's attention to it, complicates it and creates an argument.

It is difficult to settle on a definite date of the emergence of political cartooning in India. The term 'cartoon' as a humorous drawing was first coined by the British weekly magazine Punch or the London Charivari in the 1840s/50s. Around that time, India, as a British colony, experienced this new genre for the first time. Cartoon, in Punch, became a steady weapon for the British to deride the English educated new Indians who endorsed the western life style and habits. The popularity and novelty of this humour magazine caused a number of native adaptations such as the Audh Punch, the satirical Urdu weekly from Lucknow which was the first of these adaptations. In the original Punch Indian artists discovered the genre while its native counterparts gave them the space and opportunities to practice, experiment and apply this knowledge.

However, most of the cartoons of this period were not exactly what political cartoon is defined as today. But, that the social structure of India as a colonized nation came into being because of a specific political condition and a definite hegemony of power then the social satires done by the first Indian cartoonists become intrinsically political.

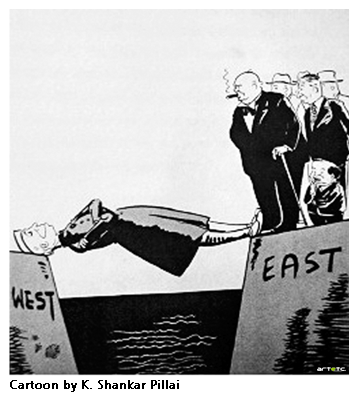

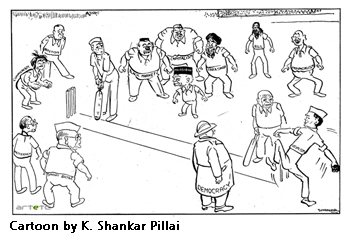

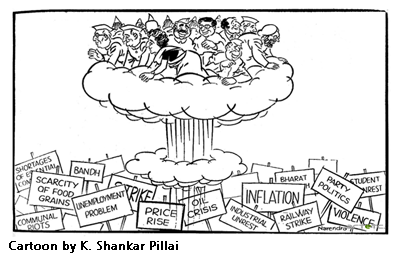

It took almost another century for the quintessential Indian political cartoonist to emerge when the Hindustan Times, Delhi appointed K. Shankar Pillai or Shankar (1902-1989) as their staff cartoonist in 1932 who continued to work in the paper till 1946. His works of this period narrated the struggles of a nation and its people on the verge of acquiring its freedom. In 1948 he started his own magazine Shankar's Weekly. He employed his weapon of humour to depict the stories and policies of the infant nation and its new leaders. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was almost a steady figure in his cartoons. Even while enjoying the prime minister's patronage and support Shankar never failed to criticize his national and international policies and humoured his verbose statements while commenting on the prime minister's experiences, burdens and difficulties of leading the newly independent nation to a yet undiscovered future. In a work dated 24 December, 1950 he shows Nehru carrying on his head an enormous pile of domestic objects and furniture while a woman calls him to inform that there are even more luggage to carry. In another one (dated February 6, 1955) the cartoonist posed a smiling Nehru as a human bridge over a dark water body connecting two blocks of land marked 'EAST' and 'WEST' while men clad in western gears unhappily look on. Nehru had numerous plans including construction of large dams, rapid urbanization and industrialization that would enable India to grow into a developed country. Shankar's comment on these plans came in the form of cartoons. In one such work titled The Artist and dated March 1, 1953 Nehru is shown to be colouring a large flower on the 'plant of planning'.

It took almost another century for the quintessential Indian political cartoonist to emerge when the Hindustan Times, Delhi appointed K. Shankar Pillai or Shankar (1902-1989) as their staff cartoonist in 1932 who continued to work in the paper till 1946. His works of this period narrated the struggles of a nation and its people on the verge of acquiring its freedom. In 1948 he started his own magazine Shankar's Weekly. He employed his weapon of humour to depict the stories and policies of the infant nation and its new leaders. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was almost a steady figure in his cartoons. Even while enjoying the prime minister's patronage and support Shankar never failed to criticize his national and international policies and humoured his verbose statements while commenting on the prime minister's experiences, burdens and difficulties of leading the newly independent nation to a yet undiscovered future. In a work dated 24 December, 1950 he shows Nehru carrying on his head an enormous pile of domestic objects and furniture while a woman calls him to inform that there are even more luggage to carry. In another one (dated February 6, 1955) the cartoonist posed a smiling Nehru as a human bridge over a dark water body connecting two blocks of land marked 'EAST' and 'WEST' while men clad in western gears unhappily look on. Nehru had numerous plans including construction of large dams, rapid urbanization and industrialization that would enable India to grow into a developed country. Shankar's comment on these plans came in the form of cartoons. In one such work titled The Artist and dated March 1, 1953 Nehru is shown to be colouring a large flower on the 'plant of planning'.

There is another side of these cartoons of Shankar. Nehru himself was an ardent follower of Shankar's cartoons about which he once remarked “Don't spare me Shankar. Hit, hit, hit me hard”. True to this, Shankar never spared him. But a question might arise in regard to this. How valid is the criticism when the person who is being criticized patronizes it? When there is an open permission to point a finger at the king to declare that he is naked is not the edge robbed a little of its sharpness? The cartoons chronicle a very important period of Indian history; chronicle the life of a very important person as well. If all the cartoons of Nehru are put together chronologically, the prime minister with all his progressive plans and programs, ages gradually. A work shows an emaciated Nehru running the last lap holding a burning torch followed by other leaders including his daughter Indira Gandhi. This work, done just ten days before the prime minister's death, hints a touch of nostalgia, like the penultimate step towards the end of a long story. These are the stories of a nation and its leader merged together. Along with being visual commentaries with immense national significance these cartoons were almost like a private game between two men armed with two powerful weapons - politics and satire.

There is another side of these cartoons of Shankar. Nehru himself was an ardent follower of Shankar's cartoons about which he once remarked “Don't spare me Shankar. Hit, hit, hit me hard”. True to this, Shankar never spared him. But a question might arise in regard to this. How valid is the criticism when the person who is being criticized patronizes it? When there is an open permission to point a finger at the king to declare that he is naked is not the edge robbed a little of its sharpness? The cartoons chronicle a very important period of Indian history; chronicle the life of a very important person as well. If all the cartoons of Nehru are put together chronologically, the prime minister with all his progressive plans and programs, ages gradually. A work shows an emaciated Nehru running the last lap holding a burning torch followed by other leaders including his daughter Indira Gandhi. This work, done just ten days before the prime minister's death, hints a touch of nostalgia, like the penultimate step towards the end of a long story. These are the stories of a nation and its leader merged together. Along with being visual commentaries with immense national significance these cartoons were almost like a private game between two men armed with two powerful weapons - politics and satire.

The genre of political cartooning is the result of a confluence of three major power structures - politics, news and media. These three are interrelated and in the absence of any one of them, the genre ceases to exist. Political news means a refined/manipulated third person version of an event that has already occurred. Cartooning is an immediate reaction to this news. Politicians, in order to gain and sustain power, rely heavily on public opinion which, in its turn, is generated by the media. Because of this and also of the fact that political cartooning, when compared to hard core political discourses, is often considered as a popular medium of entertainment and thus it is often subjected to censorship. The responsibility of a political cartoonist is to look at events neutrally without taking sides. The freedom of expression is a vital aspect not only of democracy but of cartooning as well. This aspect attributes immense power of authority over the political opinions of the public. Within the hegemonic power structures of two institutions namely politics and the corporate media houses a cartoon is thus potentially subjected to censorship from both fronts – when it contains elements or opinions that are uncomfortable for the political party and if it attests its opinion which is contrary to the principles followed by the house. According to John Keanes (quoted by Julian Petley in Censoring the World), “Those who control the market sphere of producing and distributing information determine prior to publication, what products (such as books, magazines, news papers, television programmes, computer softwares) will be mass produced and, thus, which information officially gain entry into the market place of opinion”. The third kind of censorship is imposed on a cartoon by other social forces such as religion, community and gender issues.

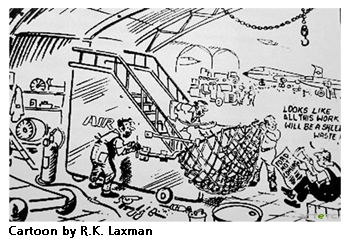

In the post-Independence India the first major incident that shook the base of Indian democracy was the Emergency period (1975-1977) under Indira Gandhi's rule when the citizens were denied their civil and constitutional rights, the press was silenced and critics, journalists, writers and common men were arrested, jailed and tortured without charge or notification of families. Private and public communication systems like Doordarshan, the national television network, were used for propaganda. Shankar's Weekly was closed during this time. The editorial of last issue dated August 31, 1975 announced “…Dictatorship cannot afford laughter because people may laugh at the dictator and that wouldn't do”. News papers were put under a severe system of censorship in order to 'stop the spreading of rumour'. Cartoons with slightest hint of what the authority thought to be anti-government would not be allowed to be published. Even those ones that were not related to emergency were censored. One such cartoon by R. K. Laxman was about Gerard Ford cancelling his visit to India. In this work he shows a panoramic view of an airport where two men try to attach a huge net on the escalator while their supervisor holds a news paper that reads “Ford Not Coming” and the man comments in annoyance “Looks like all these works will be a sheer waste”. The net was added because “During that period he somehow kept tripping and falling”. This work was banned as the censor board thought that it was “a dangerous comment on international affairs”.

In the post-Independence India the first major incident that shook the base of Indian democracy was the Emergency period (1975-1977) under Indira Gandhi's rule when the citizens were denied their civil and constitutional rights, the press was silenced and critics, journalists, writers and common men were arrested, jailed and tortured without charge or notification of families. Private and public communication systems like Doordarshan, the national television network, were used for propaganda. Shankar's Weekly was closed during this time. The editorial of last issue dated August 31, 1975 announced “…Dictatorship cannot afford laughter because people may laugh at the dictator and that wouldn't do”. News papers were put under a severe system of censorship in order to 'stop the spreading of rumour'. Cartoons with slightest hint of what the authority thought to be anti-government would not be allowed to be published. Even those ones that were not related to emergency were censored. One such cartoon by R. K. Laxman was about Gerard Ford cancelling his visit to India. In this work he shows a panoramic view of an airport where two men try to attach a huge net on the escalator while their supervisor holds a news paper that reads “Ford Not Coming” and the man comments in annoyance “Looks like all these works will be a sheer waste”. The net was added because “During that period he somehow kept tripping and falling”. This work was banned as the censor board thought that it was “a dangerous comment on international affairs”.

During the Emergency period Indian Express was one of the few papers that defied the prohibition. , the paper's staff cartoonist whose cartoons came to be known as single line editorials unsparingly criticized the authoritarian and ambitious streak in Indira Gandhi and her followers. Abraham's strip cartoon column on Emergency titled Private View was banned from publishing several times. This strip had two dhoti clad characters one fat and short and the other thin and tall. These two were apparently congress leaders whose one line speeches in the cartoons revealed the intrinsic threat advocated by the Congress party during Emergency. One such strip dated 4.7.75 is clearly marked as 'not to be published' and 'censor'. It is also signed by the person in charge. It shows the two stock characters leading a two man agitation. The tall one leads the procession with a placard that reads 'smile' and the short one follows him looking at the viewer apparently asking them what is written below 'Don't you think we've got a lovely censor of humour?' This particular strip creates a complicated web of meaning and intervention. The strongest weapon of a cartoon is its humour and it must be censored because it satirized the system i.e. the spectator is not allowed to take part in it. But in the case of this strip one can smile because the two representatives of the system permit the spectator. But the fact that one needs permission to laugh only reveals the grimness of the situation that actually dries up ones sense of humour (note the pun where the word 'sense' is replaced by 'censor'). Here the act of smile/humour becomes a weapon to subvert the totalitarian regime

During the Emergency period Indian Express was one of the few papers that defied the prohibition. , the paper's staff cartoonist whose cartoons came to be known as single line editorials unsparingly criticized the authoritarian and ambitious streak in Indira Gandhi and her followers. Abraham's strip cartoon column on Emergency titled Private View was banned from publishing several times. This strip had two dhoti clad characters one fat and short and the other thin and tall. These two were apparently congress leaders whose one line speeches in the cartoons revealed the intrinsic threat advocated by the Congress party during Emergency. One such strip dated 4.7.75 is clearly marked as 'not to be published' and 'censor'. It is also signed by the person in charge. It shows the two stock characters leading a two man agitation. The tall one leads the procession with a placard that reads 'smile' and the short one follows him looking at the viewer apparently asking them what is written below 'Don't you think we've got a lovely censor of humour?' This particular strip creates a complicated web of meaning and intervention. The strongest weapon of a cartoon is its humour and it must be censored because it satirized the system i.e. the spectator is not allowed to take part in it. But in the case of this strip one can smile because the two representatives of the system permit the spectator. But the fact that one needs permission to laugh only reveals the grimness of the situation that actually dries up ones sense of humour (note the pun where the word 'sense' is replaced by 'censor'). Here the act of smile/humour becomes a weapon to subvert the totalitarian regime

With the advent of technology the virtual space has provided with a parallel option for availing a certain measure of freedom that may or may not be always accessible in the real space. Today the personal websites, pages in the social networking sites and blogs share the same place of importance that the news papers usually enjoy. With the help of these cartoonists can transgress the barriers of time and space. But the flipside of this technological advancement is that the places that do not have the facilities of having a computer and internet services or for the people who do not know English and are not accustomed of using them would be forever outside the knowledge system that could be shared through the internet. News papers, on the other hand, can reach any corner of the universe connecting to multitude of people.

Political cartoons, in our time, have been relegated to a corner of the main body of the news papers. It is simply an accompanist of the texts rather than being a self-sufficient and complete piece of journalistic work rendered in lines. It is probably because in an age when the audience's visual faculties are constantly bombarded with a whole range of glittery and ever increasing archive of images a simple black and white drawing is bound to escape the mass attention. Furthermore, now the audience/readers are more favourable towards receiving direct information from an image. A cartoon depends on exaggeration and analogy to generate humour and it usually condenses a range of information within a small space. Thus a political cartoon is minimal and symbolic and it requires the viewer/reader to analyze and break the code that a political cartoonist creates. Also a political cartoon is time specific. Political events get old and are forgotten and along with them the cartoons that are based on them become the things of the past. For example, Shankar's cartoons today are considered to be classics with nostalgic and archival value but they belong to a time long gone.

Political cartoons, in our time, have been relegated to a corner of the main body of the news papers. It is simply an accompanist of the texts rather than being a self-sufficient and complete piece of journalistic work rendered in lines. It is probably because in an age when the audience's visual faculties are constantly bombarded with a whole range of glittery and ever increasing archive of images a simple black and white drawing is bound to escape the mass attention. Furthermore, now the audience/readers are more favourable towards receiving direct information from an image. A cartoon depends on exaggeration and analogy to generate humour and it usually condenses a range of information within a small space. Thus a political cartoon is minimal and symbolic and it requires the viewer/reader to analyze and break the code that a political cartoonist creates. Also a political cartoon is time specific. Political events get old and are forgotten and along with them the cartoons that are based on them become the things of the past. For example, Shankar's cartoons today are considered to be classics with nostalgic and archival value but they belong to a time long gone.

But the real problem with cartooning lies elsewhere. According to E. H. Gombrich “The idea persists that a comedian or caricaturist is a mere entertainer, hardly worthy of the attention of the superior persons who study and analyze the creations of serious Artists.” Humour is the foundation of a cartoon and it is its limitation. Recently there was a controversy regarding a cartoon on tsunami by the cartoonist Jayanto. In this work he had copied Hokusai's famous print of the Mount Fuji. He had shown the gigantic wave to be juggling small cars, houses, ships and aeroplanes. After the tsunami happened there was a number of photographs published that depicted mammoth waves sweeping everything within its reach. The cartoonist simply exaggerated the facts that those photos captured. A photograph, even though it can be manipulated, is thought to be able to affirm reality, fact and the unmitigated truth. A cartoonist, through personal intervention, reinterprets and reconstructs an event metaphorically and presents the essence of truth not the whole truth. Finally the touch of humour strips even the suggestion of seriousness off the cartoon in the viewer's mind. These attempts to rationalize humour in terms of today's utilitarian social structure probably explain why political cartooning, and the genre of cartooning as a whole is a dying art.