- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Dr. Seema Bawa

Art with a political or cultural purpose, be it Agitprop or protest art, remains a mere chimera and is ineffective if it is confined to high art, a domain of the elite. Genuine effective resistance comes from the universalizing of protest. Propaganda and posters become focal points or the teleological locus for such discontent and assist in converting discontent into resistance, in giving a voice to this resistance against real or perceived oppression, suppression and exploitation.

.png)

The exhibition of political posters Art Against Empire: Graphic Responses to U.S. Interventions Since World War II curated by Carol Wells at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) from 10 March to 18 April 2010 pre-fronted the role of posters in articulating protest by artists against the U.S. involvement in 40 countries covering a spectrum of protest encompassing clandestine American interventions in Chile to overt ones such as the war in Iraq.

The exhibition of political posters Art Against Empire: Graphic Responses to U.S. Interventions Since World War II curated by Carol Wells at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) from 10 March to 18 April 2010 pre-fronted the role of posters in articulating protest by artists against the U.S. involvement in 40 countries covering a spectrum of protest encompassing clandestine American interventions in Chile to overt ones such as the war in Iraq.

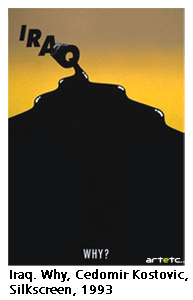

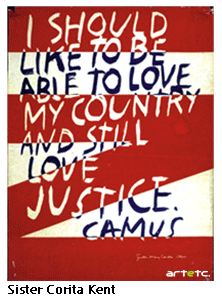

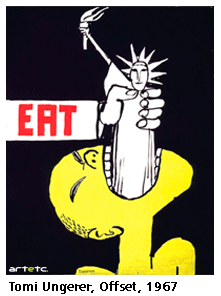

Wells is the founder and director of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, a Los Angeles-based organization that has amassed more than 70,000 political posters over the last 22 years. The centre has one the largest collection of post World War II political posters. These include posters on issues such as feminism or the prison industrial complex in many mediums and techniques. The exhibition under discussion featured works by a number of protest artists such as Josh MacPhee, Corita Kent, Jay Belloli, Cedomic Kostovic, Stephen Kroninger and others.

Art Against Empire documented over half a century of resistance to U.S. interventions into the internal affairs of sovereign nations through the powerful tool of the political poster. These interventions, many of them covert, have had severe political, economic and military ramifications resulting in undesirable loss of life, brutalization of people and untold suffering for millions. These posters showcased positively the aspirations and dreams, and negatively the pain of shattered dreams wherever aggression has been perpetrated.

The exhibition displayed over 100 political posters in the LACE galleries, and had works from two dozen countries which include Iraq, Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, Guatemala, Haiti, Cuba, Chile, Iran, and South Africa. The viewers were confronted by images that brought to life past struggles but retained a potent symbolism that was current and relevant. As is the purpose of polemical political art, they enlightened the viewers about the facts, disturb and challenge their comfortable complacency and seeked to inspire and convert. The polemics dig into the archives of past interventions and suggest the contours of incipient ones today.

The revisiting of history through this exhibition is highlighted in its diagnosis into the damage caused to these nations by their legacy colonial and imperial domination and how the malady continues in the uni-polar post colonial neo-imperialist world-order. For even a natural calamity like the recent earthquake in Haiti causes far more devastation due to Haiti's French colonial and US imperialistic legacy.

The United States was the focus of this exhibition; these posters showcased the efforts of individuals and groups that refused to be cowed down by censorship and repression which is often used in the name of national interest and Security. People who went against the grain of common public opinion, which is generally jingoistic in the US, utilized the power of the image and the written word to arouse action through posters.

Viewed collectively, the works knit together rubric which showed people ranged against powerful states and government while tracing a global current of dissent against state power. "A poster will yell something… but you put them together and they scream", said curator Carol Wells.

The impact of the works was in-your-face and designed to shock; the “screams” did not yield to mere cacophony but to an alternate rhapsody of raw perpetual human dissent against endemic state brutality.

The posters on display were divided into two broad categories, the first posters made in the US itself by sensitive conscientious citizens and the second, posters made in countries which saw themselves as victims of US aggression.

One can trace patterns in these posters; posters made in the U.S. usually showcase human suffering through depiction of victims of war. One of the best-known posters exhibited was a photograph of tangled, bloodied bodies taken in the aftermath of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam. Printed across the image was a snatch of war journalist Mike Wallace interview with an American soldier who participated in the incident. Wallace asked who the soldiers killed: "And babies?" The response: "And babies.” That poster in question, according to the curator Wells helped turn the tide of public opinion against the Vietnam.

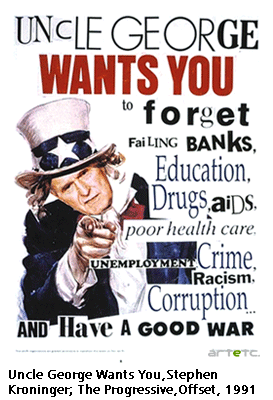

The popular opinion in the anti American public has been of a global bully, an anti-peace nation, imposing war not only to promote its agenda of aggrandizement but also to create demand for its arms industry. It is no wonder that in one of the posters George Bush Jr, the engineer of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, was shown as Uncle Sam urging people to forget the failed domestic policies that encouraged poverty and exploitation but to Have a Good War: a biting satirical comment on the cupidity of the government. As Henry IV advised “Be it thy course to busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels,” in Shakespeare's historic play.

Posters made in countries protesting U.S. involvement project their struggle through symbols borrowed from their own cultural practices or kinship based bonding as a counter to the brutalizing homogenizing US weltan- schuang. A Cambodian poster from the 1970s showed a man sitting in the lap of Buddha, pointing a gun; a poster from Nicaragua showed a smiling woman with a baby pressed to her chest and a machine gun slung over her shoulder.

Nancy Spero illustrated the torture tactics used against women in Chile, highlighting the dual oppression, based on gender and ethnicity, faced by women in patriarchal societies. Dominant nations and military tacticians have been using violence against women, including rape to demoralize, humiliate the enemy and also to mark their victories. Women and children were the most vulnerable to violence.

As has been demonstrated by Gerda Lerner in the Creation of Patriarchy, historically women as a category were the first to be enslaved in wars not only because they lack physical prowess but because of their role as nurturers and mothers: women are reluctant to abandon their children to escape the enemy and are therefore easily captured. The practice of perpetuating violence against women as a class has continued over 5000 years at least and as the posters demonstrated is not confined to so called 'under developed' nations but has been adopted by all aggressors, national and international.

Many posters by feminist organizations targeted such anti women aggression by US forces against women, especially where female combatants had themselves taken part in military action. It was no wonder that in one of the posters a female American soldier was shown dressed in fatigues and the text were, "Did she risk her life for governments that enslave women?"

The posters obviously demonstrated the time and age in which they were created, the latest engaged with the latest technology, both as a tool and as visual. Using the I-pad advertisements as a take off point these posters showed white silhouettes against colourful backgrounds, but rather than jamming to music, the figures carried guns. In the upper corner, where the word "i-Pad" should have been, was inscribed "i-Raq," an indictment of US aggression and occupation.

The effectiveness of posters as a medium of protest has been demonstrated repeatedly largely based on the anonymity of the producer and the consumer of protest art, as well as on the collective angst that leads to their production. In the Anti- Apartheid struggle, artists such as William Bester used T-shirt slogans and posters to propagate their message, though their names were never appended to these.

"If the people behind the posters didn't believe that we could change the world, they would never make them,” explained the curator. Posters translate resistance from mere critique to action. And any documentation of human action against oppression must take these into account, not only for their historical value but also for the popular cultural consciousness and collective symbolism that they represent.