- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Claudio Maffioletti and Leandre D'Souza

For most of us browsing through our idiot boxes or feeding off junk from our internets, it seems like 2011 was the year of protest. There was an ebullient uprising by people everywhere. All hell broke loose with the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries unleashing fury and disgust at dominant political structures.

India too had its outpouring with the Anna Hazare anti-corruption protests and finally, most memorably we tuned our channels and antennas towards the Occupy Wall Street outburst against the capitalist moghul of our planet. Whether blockades, demonstrations, banners, marches, camps, damaging property, militant struggles we have seen these voices of dissent flicker daily on our screens.

This is literally the rage against the machine new kind of “peaceful” warfare that is brewing and blowing over hegemonic institutions globally. For artists embroiled in politically engaging or protest prone art, their work takes the form of a cultural resistance while reflecting and critiquing socio-political and economic situations. Artistic practice functioning within this realm provides a voice to existing social movements and creates a space where they can all be heard collectively. Indeed, art has the potential to bring together different arguments and viewpoints that can inform processes of protest and revolutionary ideas. What art is meant to do is to consider alternative ways to reorganize our societies through participation, relations, dialogue and solidarity. But is it really so?

Through this essay, we will show how these spurts of protest art keep recurring throughout history, ignited by avant-gardist movements and further developed later depending on the contexts in which they find and present themselves. By highlighting specific artistic movements that challenged the deadpan boredom of capitalistic modernity through unpredictable, unimaginable ways, what we will try to illustrate is a common thread that puts these isolated forms on one platform so that we can assess, question and learn from them. At the same time, it is important to examine what happens to these marginal or extremist movements when aesthetic production is commodified into mainstream capitalistic systems.

An article recently written by artist Martha Rosler on political and socio-critical art practices tries to provide an answer to the question "whether choosing to be an artist means aspiring to serve the rich...”. Rosler's candid dilemma subsumes another foundational doubt: are the attempts to resist and deconstruct existing systems of power destined to be silently yet unfailingly reabsorbed by the same?

An article recently written by artist Martha Rosler on political and socio-critical art practices tries to provide an answer to the question "whether choosing to be an artist means aspiring to serve the rich...”. Rosler's candid dilemma subsumes another foundational doubt: are the attempts to resist and deconstruct existing systems of power destined to be silently yet unfailingly reabsorbed by the same?

The need to question and try to subvert the presumed autonomous statute of art through provocative and rupturing practices has been at the heart of art discourses of the last millennium, and has defined those of the new one. In his classic work on the avant-gardes, Peter Bürger dismisses historical avant-gardes as failed attempts to reunite the separation of art from the praxis of life operated by bourgeois society. The Dadaist destruction of traditional art categories and conventions, the surrealist reconciliation of subjective transgression and social revolution, the constructivist intention to make cultural means of production collective were finally phagocytized by the capitalistic and consumerist tenets intrinsic in modern societies. In his perspective, the artistic production of the neo-avant-garde in the years after the Second World War was at the best the farcical repetition of a capital mistake.

Hal Foster's approach to the avant-gardes is more problematic, as he posits that their “aim is neither an abstract negation of art nor a romantic merge with life but a perpetual testing of the conventions of both”. What can be saved in avant-gardist practices is precisely their exploration of the tension between art and life. With regards neo avant-gardes, Foster identifies their main novelty in the focus given to the institution, as opposed to historical avant-gardes who were more interested in conventions.

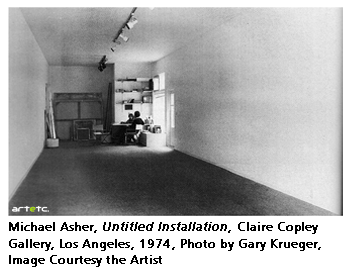

Active at the end of the '60s, artists like Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, Michael Asher and Hans Haacke initiated “a creative analysis at once specific and deconstructive” of the exhibition status, of its institutional nexus and of artists and art institutions' inexorable implications in the socio-political value system. One of the recurrent subjects of their works has been the role of the modern art museum and its functioning as a public and private institution. Haacke's provocations were particularly effective, as their deconstruction of the institution's nature and hidden structures managed to operate a short-circuit within its very structure of meaning. Emblematic is the case of Haacke's exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1971. As the artist planned to display the documents he carefully collected on the property holdings of New York City slumlords, thus exposing to the public some of the Museum's trustees, the Guggenheim decided to cancel the exhibition, and to dismiss the curator Edward Fry who opposed the decision. In 1974, the artist submitted to the Wallraf-Richartz museum in Cologne a proposal to display a well-documented history of the ownership of Manet's painting Bunch of Asparagus in the museum's collection, narrating how it came into the collection, and in which the Third Reich's activities of its donor were revealed. The proposal was rejected, but Haacke's moral obligation to make the project's implications clear still intact.

Active at the end of the '60s, artists like Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, Michael Asher and Hans Haacke initiated “a creative analysis at once specific and deconstructive” of the exhibition status, of its institutional nexus and of artists and art institutions' inexorable implications in the socio-political value system. One of the recurrent subjects of their works has been the role of the modern art museum and its functioning as a public and private institution. Haacke's provocations were particularly effective, as their deconstruction of the institution's nature and hidden structures managed to operate a short-circuit within its very structure of meaning. Emblematic is the case of Haacke's exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1971. As the artist planned to display the documents he carefully collected on the property holdings of New York City slumlords, thus exposing to the public some of the Museum's trustees, the Guggenheim decided to cancel the exhibition, and to dismiss the curator Edward Fry who opposed the decision. In 1974, the artist submitted to the Wallraf-Richartz museum in Cologne a proposal to display a well-documented history of the ownership of Manet's painting Bunch of Asparagus in the museum's collection, narrating how it came into the collection, and in which the Third Reich's activities of its donor were revealed. The proposal was rejected, but Haacke's moral obligation to make the project's implications clear still intact.

Whilst institutional critique artists operated within the domain of the museum, the gallery and the art system at large, questioning their functioning and bringing to the surface their inner contradictions, other, earlier movements were more interested in utopian ideals to disenfranchise human beings from consolidated social structures and to fight for counterhegemonic, alternative and radical codes of behaviour.

Originating in the 1950s, Situationist International devised a program through which capitalism and communism could be done away with to make room for an anarchist social democracy. By rupturing the spectacular from society that perpetuates people towards apseudo-belief system conditioned by material wealth, their intent was to create new forms of social life. Returning to playfulness and moments of pleasure, they drifted through the city constructing situations through the technique they called the dérive. By manifesting the desire to become “psychogeographers”, the Situationists tried to make aware and subvert the basic framework by which everyday life is controlled and structured. Unleashing the fetters of daily life, they engaged in behavior that releases repressed desires of the city. Turning the present situation on its head, the détournement served as an intrinsic tool to expose the trappings of a commodity-frenzied society. Using billboards, comics, films, man's hidden desires would be finally liberated through this revolutionary process. Thus, what would emerge is a leaning towards unification and communality in the public urban realm rather than commodification, fragmentation and privatization.

While the Situationist International was a militant group operating out of Europe with a long history of anarchism, trade unions and labour struggles at a time when major powers in the world league were dominated by both capitalistic ideologies and communist dictates, Fluxus emerged on the map as a parallel movement around the same time. This was the era of conflict the Cold War, a nascent United Nations, Vietnam war, Civil rights movement.

Fluxus, like the name itself suggests, transformed in its fluidity the way the world considered art and altered the relationship between art and life. Their processes were simple, subtle, ephemeral and played on notions of touch, sight, smell and at other instances like jarring vocal reverberations that shattered preconceived ideas of the subliminal artistic experience. The artists part of the group intended art as an all-encompassing and transformative human experience. Encouraging a crossbreeding of art, music, design, architecture, those involved in Fluxus forms incorporated simple elements that combined to shape and evolve a complex environment. As this was a new way of living, boundaries were demolished. The Fluxus idea was to put forth a democratic approach to culture and life that was anti-elitist, anti-nationalist, thus suggesting a world where it was possible to get the greatest value for the greatest number of people. The ideas by which Fluxus intended to shift the paradigm of dominant structures was through globalism, unity of art and life, intermedia, experimentalism, chance, playfulness, simplicity, implicativeness, exemplativism, presence in time and musicality.

Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys felt the need to provide an extended definition of art ('every man is an artist'), one which could identify art practices as an evolutionary and revolutionary power meant to act as an agent for change and re-organization. He formulated his utopian hypothesis of society as a work of art, a social sculpture, a living organism which evolves with the creative contribution of each person.

In his manifesto I Am Searching for Field Character, 1973 Beuys articulated that only art is capable of breaking down social systems in order to build a Social Organism as a Work of Art. For him, Social Sculpture would only take place when man becomes a creator. “Only a conception of art at this level can turn into a politically productive force, coursing through each person and shaping history.”

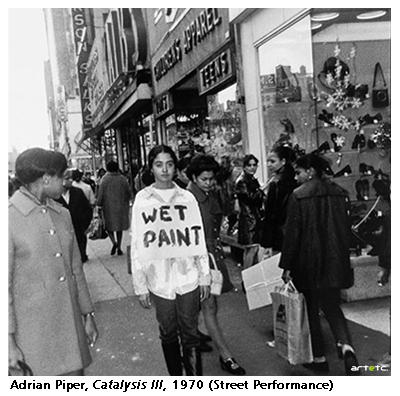

If art is the tool to facilitate change, to trigger the audience's creativity, to guide subjects to reach their own productive capacities, to enable them to reach a greater awareness of their realities, then it is first necessary to underline how our individual belief systems are constructed. Adrian Piper, through a series of confrontations of the self and self in relation to others, tried to expose the alienation between people on a personal, political and emotional level.

Piper's investigations were records of her Catalysis series, unannounced street performances that were explorations of her own identity race colour self. Her work was defined as 'identity politics' connecting racial, class and sexual subjectivity to institutions and processes of power. Her social interventions were part of a study to test people's reactions to a disruptive presence- her repellent self; woman in forms that one does not expect to see. By presenting herself in these exaggerated situations, she started cataloguing the reactions she got and the unconscious processes that were already in play on the part of both the artist and the public in the moment of performance.

According to Piper's findings, ideology itself is dangerous. It is an illusory construction where one confuses experience with reality, disregarding the subjective self that selects, processes and interprets experiences according to one's own limited capacities. One solution Piper proposed from her analysis was confrontation to start doubting and questioning which would slowly dismantle one's structures of belief. An extension of Piper's '70's experiments was the 1986-1990 Calling Card performances where she handed out a card to people she met and who made racist comments in front of her at dinners and cocktail parties. It read:

“I am black. I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark. In the past, I have attempted to alert white people to my racial identity in advance. Unfortunately, this invariably causes them to react to me as pushy, manipulative, or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are no black people present, and to distribute this card when they do. I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.”

Calling Card urged a more direct and intimate confrontation during these social encounters, leaving an indexical recognition or non-recognition of her colour at that precise moment, acting as a catalyst for social awareness of interpersonal relations. Piper believed that art reflects society and that a lot of the work she was doing was being done because she was a paradigm of what society is/was.

Istanbul-based Resistanbul instead employs a more straightforward, activist approach to issues of housing, safety, health, job security, migration specific to Turkey. For them, change occurs in the streets they call for bonfires, agitations, protests tactics to loose capitalism and its trappings. Their hardcore activism also leaks into a critique of the arts system itself and how works of dissents get appropriated into institutions. Yet these works reform the institution, even if momentary.

Parodying the commodification of the art market and the reification of human beings as sexual objects, ArtOut provides an escort service by making available artists on rent for culturally scintillating evenings with. ArtOut is an experimental project commenting on fetishism and the role and identity of artists themselves. So instead of attaching value only to the work by their artist base, they attach fair value of trade to their artists. Here resistance is visible by transferring expressions of neo-capitalistic habits on to an artistic side and trying to break them down from the inside.

If we freeze all these instances of agitation throughout recent history and within the contexts in which or outside which they are produced (the art world, galleries, biennales, art fairs, art festivals increasingly proliferating in every corner of the planet), perhaps their most poignant and recurrent feature is their flexibility, their ability to shift from the purely artistic to the political. What art does is to provide us with a number of options where we have the freedom to question and to suspend our choice. So, what use are a couple of words placed together inviting us to focus on one word and repeat it until dawn as Yoko Ono's recent retrospective at Vadehra did? Whilst challenging the very boundaries of human will and power, it discloses the impossible magic of utopia. “It is in [the] gap between the work's production and its absorption and neutralization that allows for its proper reading and ability to speak to present conditions. It is not the market alone […] that determines meaning and resonance: there is also the community of artists and the potential counterpublics they implicate”. Systems exist. Art can enable us to doubt them.