- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

Uma Prakash in conversation with Shibu Natesan

Uma Prakash: You belong to a generation of artists from Kerala who studied at the College of Fine Arts in Trivandrum during the early eighties. Was this a time of continuing change and rebellion against a bureaucratic and stultified art establishment?

Shibu Natesan: There is a huge gap between Ravi Varma and KCS Paniker in the history of Kerala art. Most Kerala artists studied under KCS Paniker in Madras except for Madhava Menon, K. G. Subramanyan and A Ramachandren (they studied in Santiniketan till the 70s). The kind of art practiced in Madras was very different from that of the progressive artists of Mumbai or the rest of India. The art practice of Madras artists was deeply rooted in Indian philosophy but it was not appreciated in Kerala the same way as literature or cinema in the 60s and 70s. The reason for this was because of the strong intellectual nature of it which the common man could not appreciate. Most of the artists of the 80s and 90s of Kerala studied at the college of Fine Arts Trivandrum. The figurative artistic language developed from this period was very different from the previous generations' geometrical abstract art. The student's interests and references were very different from the famous art schools such as Baroda or Santiniketan. The Baroda art scene was quite close to the British narrative art but Trivandrum artists were referring to the German expressionists and symbolists artists. Trivandrum artists made emotionally charged paintings and sculptures which were not thematic in the way that Baroda artists tended to work.

So much availability of literary publications such as Little Magazines enabled Latin American and African literature to be available. Aksharam, edited by poet A. Ayyappan was the first and important one. The accessibility of international art films and extreme cultural and political movements such as Naxalism had a very strong impact on artists.

U P: Tell us about your first significant body of work, a series of paintings entitled The Futility of Device. Is it a fusion of feudal history painstaking detailed with relics?

S N: In 1995 I painted the series of paintings, Futility of Device, as a reaction to the Babri Masjid demolition by Hindu fundamentalists. The paintings were almost monochromatic in colour treatment, kind of grey paintings. All these paintings had an investigative nature and they were all an interior themes.

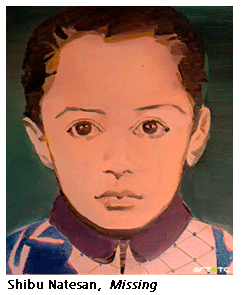

U P: After spending two years, between 1996 - 97 at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, you created the Missing series of paintings. Is it representative of the change that occurred during the time?

S N: In 1996- 97, I was awarded a grant from the Unesco Aushberg to work for two years in the Rijsakademie in Amsterdam; it was a significant period in my life as a painter. Holland has a strong history in painting and my wife and I used to travel around provincial towns looking at the art museums. We saw the work of many artists not mentioned in art books or who were very rare so I got the chance to explore these paintings which then created in me a strong confidence in painting. Also meeting and discussing painting with painters like Luc Tuymans and Emo Verkerk was interesting. The experience of small and personal paintings like those of Jan Mankes and Leon Spilliaert were significant (Dutch paintings were small in size expect for a few painting like Night watch by Rembrandt). After returning from Holland in 1998 I started a series of small oil painting called Missing which were small and personal in nature. I showed these works in Baroda, Delhi and Mumbai.

S N: In 1996- 97, I was awarded a grant from the Unesco Aushberg to work for two years in the Rijsakademie in Amsterdam; it was a significant period in my life as a painter. Holland has a strong history in painting and my wife and I used to travel around provincial towns looking at the art museums. We saw the work of many artists not mentioned in art books or who were very rare so I got the chance to explore these paintings which then created in me a strong confidence in painting. Also meeting and discussing painting with painters like Luc Tuymans and Emo Verkerk was interesting. The experience of small and personal paintings like those of Jan Mankes and Leon Spilliaert were significant (Dutch paintings were small in size expect for a few painting like Night watch by Rembrandt). After returning from Holland in 1998 I started a series of small oil painting called Missing which were small and personal in nature. I showed these works in Baroda, Delhi and Mumbai.

U P: Were you influenced by the films of John Abraham and G. Aravindan?

S N: In the 60's to 80's there were a large number of art film makers in Kerala. Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Arravindan, John Abraham, Pavithran, P. A Bekker were the prominent names. These films were all personal and political at the same time. Adoor and John Abraham were studied under the great Ritwik Ghatak. In the 80s there were a few significant film clubs like Surya and Chalachithra which screened international art films in Trivandrum. So we students of the Fine Arts were well exposed to the cinema culture then and that strongly influenced our art.

U P: Did the translations of Latin American and African literature impact your way of thinking?

S N: We were exposed to translations of African and Latin American literature. Writers like Pablo Neruda, Nicolas Gillan, Borges, Garcia Marquez and Wol Soyinka were among them.

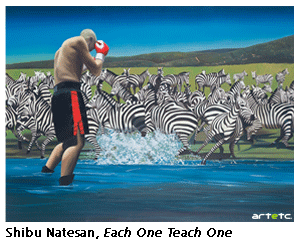

U P: You enjoy painting animals in your paintings. Is it easier to get your message across with them?

S N: Existence of Instinct and Each One Teach One were shows where I explored many animal images and the instinctive nature of animals. In these paintings I explored that part of human nature which seeks to control I explored the relationship between the one who seeks to be powerful and the one who is the object of that power or lust. Human, animal, bird, fish etc are all sentient beings. Objectively for a painter painting human figures and animals are the same. The difference is in our associations and meanings.

S N: Existence of Instinct and Each One Teach One were shows where I explored many animal images and the instinctive nature of animals. In these paintings I explored that part of human nature which seeks to control I explored the relationship between the one who seeks to be powerful and the one who is the object of that power or lust. Human, animal, bird, fish etc are all sentient beings. Objectively for a painter painting human figures and animals are the same. The difference is in our associations and meanings.

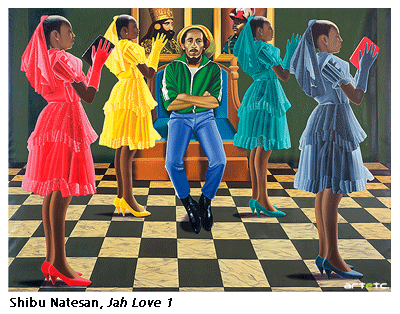

U P: Were you exploring Bob Marley's Rastafari movement when you painted Jah Love with him as the central character?

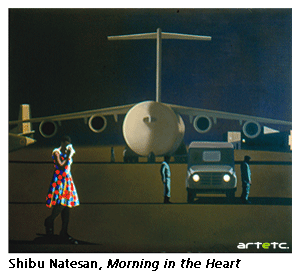

S N: I first heard Bob Marley in 1989 when I was a student in Baroda. The music and Rastafarian ideology interested me very much. Then I started exploring other musicians of reggae. One of the things that interested me was the philosophy of non-dualism present in Indian philosophy as well as Rastafarianism. It also has lots of other similarities in its beliefs and way of living. My interests in reggae lead me to study African history. I have done a few painting based on this subject matter. Morning in the Heart, a painting for Patrice Lumumba' was one of the significant works by me.

S N: I first heard Bob Marley in 1989 when I was a student in Baroda. The music and Rastafarian ideology interested me very much. Then I started exploring other musicians of reggae. One of the things that interested me was the philosophy of non-dualism present in Indian philosophy as well as Rastafarianism. It also has lots of other similarities in its beliefs and way of living. My interests in reggae lead me to study African history. I have done a few painting based on this subject matter. Morning in the Heart, a painting for Patrice Lumumba' was one of the significant works by me.

U P: In your view which contemporary Indian artists have successfully portrayed Protest art?

S N: In my view art is always born from some sort of protest. Indian artists like Krishan Khanna, Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh, T.V. Santhosh, Riyas Komu all expressed a political comment born out of some aspect of protest.