- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

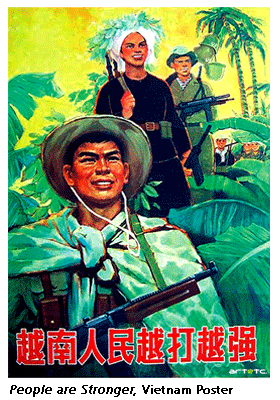

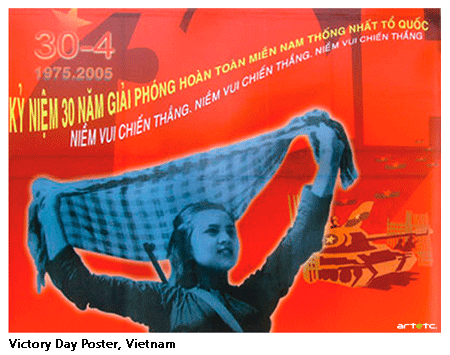

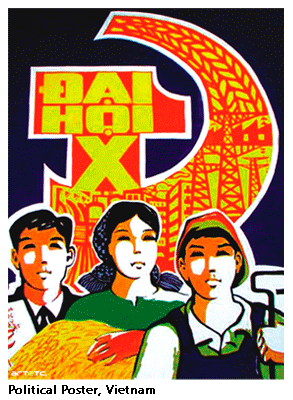

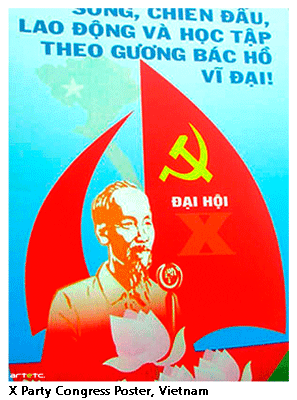

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Up Against the Wall

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Dr. Manisha Patil

'There never was a good war, nor a bad peace' – Benjamin Franklin

'Recycle Nixon!'- they demanded. 'Amerika is Devouring its Children!' 'Peace Now!' they beseeched. The origins of posters on political protest in the United States rewind back to the late nineteen sixties and early seventies. The scene of the action- campus of the University of California in Berkeley. The prime incitement- the Vietnam War and America's prolonged involvement in the military conflict.

The Berkeley campus had, as early as 1964, spearheaded the Free Speech Movement under the leadership of Mario Savio. The movement mobilised students to lend solidarity to the anti war stir which by the beginning of 1965, had disseminated to a number of college campuses across the nation. 'Vietnam Day', a symposium held in Berkeley in October 1965 drew thousands to debate on the moral basis of war. Students all over the nation felt the undercurrents of America's intervention in the Vietnam War fought bitterly in a locale thousands of miles away. President Richard Nixon's policy of Vietnamization was viewed with suspicion. Television and newspapers that brought into American homes the harsh realities in graphic detail intensified the fear and acrimony generated by the war. The goriness of it all was essayed in the mindless My Lai massacre by U.S. troops and the napalm tragedy, media images of which lingered on and haunted public memory till long after. Soon followed the unfortunate incident at Berkeley's People's Park, where Governor Ronald Reagan, publicly critical of campus demonstration, issued orders to prevent a mass rally at the venue. The situation went out of hand during confrontations between police and the students as well as residents leading to the death of an innocent student, James Rector in police firing in May 1969. By 1970, student leaders intensified stirs, calling for national students' strikes. President Nixon's inflammatory references to student radicals as 'bums,' which according to a media report was 'the strongest language used by the President publicly on the subject of campus violence' catalyzed the dissent. The nation was indeed simmering, Berkeley more so.

The Berkeley campus had, as early as 1964, spearheaded the Free Speech Movement under the leadership of Mario Savio. The movement mobilised students to lend solidarity to the anti war stir which by the beginning of 1965, had disseminated to a number of college campuses across the nation. 'Vietnam Day', a symposium held in Berkeley in October 1965 drew thousands to debate on the moral basis of war. Students all over the nation felt the undercurrents of America's intervention in the Vietnam War fought bitterly in a locale thousands of miles away. President Richard Nixon's policy of Vietnamization was viewed with suspicion. Television and newspapers that brought into American homes the harsh realities in graphic detail intensified the fear and acrimony generated by the war. The goriness of it all was essayed in the mindless My Lai massacre by U.S. troops and the napalm tragedy, media images of which lingered on and haunted public memory till long after. Soon followed the unfortunate incident at Berkeley's People's Park, where Governor Ronald Reagan, publicly critical of campus demonstration, issued orders to prevent a mass rally at the venue. The situation went out of hand during confrontations between police and the students as well as residents leading to the death of an innocent student, James Rector in police firing in May 1969. By 1970, student leaders intensified stirs, calling for national students' strikes. President Nixon's inflammatory references to student radicals as 'bums,' which according to a media report was 'the strongest language used by the President publicly on the subject of campus violence' catalyzed the dissent. The nation was indeed simmering, Berkeley more so.

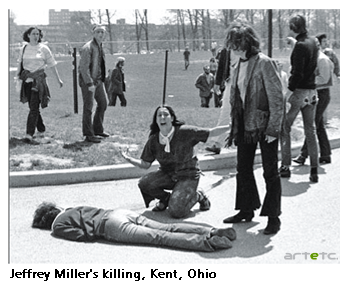

It was in late August, in the year 1969, that Dr. Thomas Benson, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Rhetoric in Penn's State's Department of Communication Arts, arrived in Berkeley as visiting faculty. A few months later, violence erupted on the campus, triggered by the unreasonable and imprudent attack on the students by the National Guard inside the campus of the Kent State University, Ohio, on the 4th of May 1970. The guns snuffed life out of four innocent students and left nine others grievously injured. The incident intensified the national protest even as Nixon disclaimed responsibility for it. The last straw was President Nixon's attack on Cambodia in 1970, an uneasy portent of the turbulent times that were to follow.

The protest art posters in Berkeley need to be viewed against the backdrop of these tumultuous socio-political circumstances. The university campus by 1970, turned into a venue for frenzied activity of poster making on political protests- opposing the Vietnam War, and decrying the policies and actions of President Nixon and his Government. As America witnessed an intensely political climate that led to the most vicious form of campus violence, with about five hundred colleges and universities across the country closing down, Berkeley students held forth stoically, remaining on campus, armed with the slogan-'On strike, keep it open!' The poster campaign gained momentum as hundreds of them were produced and laid down in stacks in the lobby of the School of Environmental Design. Dr. Benson remembers how there was a fresh supply of the posters every single day, with variety in designs and ideas. They were distributed free, soon appeared on campus windows and were plastered all over the city, finding their way into homes and offices. Dr. Benson, as a first person witness to campus violence (he recalls how a tear gas grenade was planted in the window of his classroom) and his speciality in the rhetoric of American politics and culture, assiduously collected about seventy of these unique anti war posters, and after nearly forty years of living with them Benson donated them to the Penn State library, where they were put up in a special exhibition in the winter of 2011. The title Up Against the Wall was adopted, as Benson elaborates, 'as a pun of sorts, evoking the well known phrase of that day and making references to the posters up on the wall'.

The Berkeley anti-war posters derived inspiration from the anonymous anti establishment propaganda posters of Paris produced in 1968 in massive numbers. These were made by the striking students and teaching faculty of the Ecole des Beaux Arts at what came to be known as the 'Atelier Populaire', and which flooded every nook and corner of France. As Benson explains, 'the Berkeley posters captured “the intensely political climate and emerging student engagement with war, patriotism and anti-imperialism” and were 'an appeal for calmness, participation and inclusion.'

These posters, small in size but telling, reflect the period of confusion and turmoil. Many of them were printed on easily available material such as computer paper with perforation marks on either edge. A miscellaneous mix, they embrace various techniques such as regional art and silk screen, and include typographic posters, drawings and mechanically printed reproductions of photographs. Mostly in monochrome, they employ a basic colour palette of reds, blues and greens, blacks and browns. Many of them have tiny numbers inscribed in the lower margins, given by the police to indicate that permission had been granted for their display in public spaces.

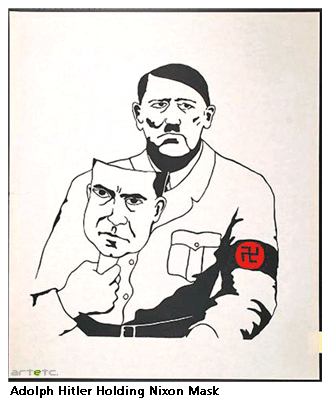

Striking in their economy of means, many of them revolve around Nixon, the focus of collective angst nationwide. In one of the posters, Nixon's head manifests as a mask, held by none other than Adolph Hitler, the trademark swastika figuring conspicuously on the dictator's arm band. This Berkeley poster is a solitary example wherein the imagery is directly borrowed from a similar work from 'Atelier Populaire' of Paris, featuring Hitler holding forth a mask of the French leader Charles de Gaulle.

Other artworks are quintessentially American, dredged from contemporary consumer culture as also media coverage, such as an iconic poster where Nixon makes an appearance as a caricature in a striped tee shirt, sucking his palm and holding his security blanket, the creased U.S. flag to his cheek. The bubble at the top reads 'Security is the silent majority!' The caption is an allusion to both the character of Linus from the popular comic strip 'Peanuts,' invoking the wisdom that security is a warm blanket and to Nixon's famous speech of November 3rd 1969, delivered slightly prior to the events of May 1970, in which he described what he called his quest for peace in Vietnam and remarked- 'And so tonight to you, the silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support!'

Resentment against war targeted other political personalities as well. Attention often shifts to the U.S. vice president Spiro Agnew, known for his scathing criticism of political opponents, particularly journalists and anti-war activists. As the political spokesperson and Nixon's 'hatchet man,' he delivered some of the harshest speeches. The poster carrying the slogan An Effete Corps of Impudent Snobs mocks one of Agnew's infamous orations. In another case Agnew is appropriated as Big Brother, the fictional character from George Orwell's novel 'Nineteen Eighty Four', the mindless dictator of the totalitarian state of Oceania. Since the publication of this novel, 'Big Brother' had entered the lexicon as a synonym for abuse of government power. Big Brother may have stemmed from Alfred Leete's historic poster of 1915 of Lord Kitchene who was involved conspicuously in British military recruitment in World War I. This in turn inspired J.M. Flagg' to create the very American 'Uncle Sam' an intimidating character whose sternness is enhanced by an expressive and virtually inescapable gesture of pointing out to the spectator, issuing the command -I want YOU in the U.S. Army! This gesture, a metaphor for authority and dominion, is deployed to image President Nixon as well.

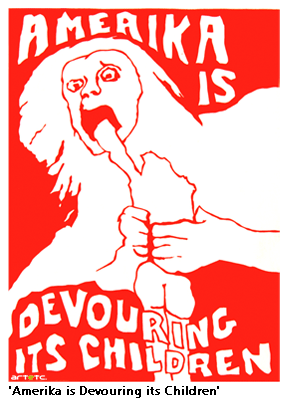

The appropriation assumes a more sinister and pessimist note in another poster modelled after a celebrated painting from the morbid Dark Series of the Spanish Painter Francesco Goya. The painter's remarkably naturalistic image of a fierce looking Saturn in the act of devouring his own son is now presented in its graphic version in monochrome, accompanied by Amerika Is Devouring Its Children!

The appropriation assumes a more sinister and pessimist note in another poster modelled after a celebrated painting from the morbid Dark Series of the Spanish Painter Francesco Goya. The painter's remarkably naturalistic image of a fierce looking Saturn in the act of devouring his own son is now presented in its graphic version in monochrome, accompanied by Amerika Is Devouring Its Children!

Many of these posters exhort the civilians to break their silence, 'to speak up, to stand for their rights', employing perfunctory illustrations to carry forth the message. One such poster delineates cogs of a military machine, puppet like human figures, with flayed hands suspended within them. 'Don't be a silent part of the war machine, speak up against Cambodia,' it declares. Another has repeats of schematized faces, the mouths shut tight, with a singular exception of an expressive face with radiating lines and a gaping mouth looking as if it is the only one daring to speak up. Referring to Nixon's oration, the slogan informs-'Don't be 1 of the silent majority, Speak out.'

Peace posters are aplenty, mostly introducing the familiar dove motif as a cut out or treated in more elaborate arabesques inspired by Art Nouveau designs. Poster designers also tweak the U.S. flag, occasionally with colour switches that also deliberate on issues concerning environment. For example, the green standard proclaiming Recycle Nixon! Or more piercingly, alluding to warfare as in the poster wherein the white stars and red stripes are replaced by war planes and rifles respectively. Some categorically refer to the commerce of war- Money Talks! Boycott War Profiteers, incorporating a graphic representation of a dollar bill.

Some posters examine the Asian perspective, and pick out the plight of the war stricken Vietnamese civilians- A poster delineating a Vietnamese peasant, identifiable by his characteristic South-east Asian conical hat alongside a buffalo, carries the slogan 'Does he destroy your way of life?' Others tug at emotional strings: Vietnamese mother hugs her son- 'this is life,' and with a gun below, 'this cuts it short.'

The efficacy of an image heightens if it realistic, necessitating the deployment of technology as a tool. Posters often adopt photographic techniques with juxtapositions of emotionally charged typography. Such works correlate with television presentations evoking the full message in a single picture. A poster in vibrant pink and stark black refers to the Kent campus killings and revives the tragic death of Jeffrey Miller, whose face added as an inset, lends authenticity to the sorrowful event. It is based on an iconic photograph by John Filo clicked minutes after. The message reads thus- “All his parents' love and devotion could not save the life of this boy. You can help save the lives of others,” concluding with an appeal “Work for peace,” and lastly adding in minute letters, a list of 'Things you can do…'

The efficacy of an image heightens if it realistic, necessitating the deployment of technology as a tool. Posters often adopt photographic techniques with juxtapositions of emotionally charged typography. Such works correlate with television presentations evoking the full message in a single picture. A poster in vibrant pink and stark black refers to the Kent campus killings and revives the tragic death of Jeffrey Miller, whose face added as an inset, lends authenticity to the sorrowful event. It is based on an iconic photograph by John Filo clicked minutes after. The message reads thus- “All his parents' love and devotion could not save the life of this boy. You can help save the lives of others,” concluding with an appeal “Work for peace,” and lastly adding in minute letters, a list of 'Things you can do…'

For a nation which was to witness the emergence of protest art in a significant manner in the ensuing decades, such as the recent Occupy movement, the Berkeley posters, as visual rhetoric, assume a central position. As Benson puts it, “As physical objects they are fragile, but they can travel through the public and stand temporarily in one's path. The obviously cheap, vocal and immediate materiality of the posters, their familiarity, the vernacular wit, occasional graphic distinction and anonymity gave them, in the context of time and place, an authenticity. Picking up one such poster, pasting it up on the walls of one's home or office or carrying them in a peace march became an act of solidarity.” None of these posters advocate violence, the stone throwing, and arson which the President and other authorities harped about. They are informed with a certain restraint and speak the language of a peaceful dissent and patriotism. As a collective voice of a strife torn nation, the historical value of Berkeley posters can in no way be undermined.

Bibliography.

1) http:// www.libraries.psu.edu/psul/digital/benson.html

2) Gallery talk: Up Against the Wall: Political Protest Art from the Thomas W. Benson collection, live. libraries. psu /mediasite /viewer/peid

3) The Rise and Fall of the Poster, Maurice Rickards, 1971