- Editorial

- Shibu Natesan Speaks on Protest Art

- Rising Against Rambo: Political Posters Against US Aggression

- Transient Imageries and Protests (?)

- The Inner Voice

- Bhopal – A Third World Narrative of Pain and Protest

- Buddha to Brecht: The Unceasing Idiom of Protest

- In-between Protest and Art

- Humour at a Price: Cartoons of Politics and the Politics of Cartoons

- Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

- Up Against the Wall

- Rage Against the Machine: Moments of Resistance in Contemporary Art

- Raoul Hausmann: The Dadaist Who Redefined the Idea of Protests

- When Saying is Protesting -

- Graffiti Art: The Emergence of Daku on Indian Streets

- State Britain: Mark Wallinger

- Bijon Chowdhury: Painting as Social Protest and Initiating an Identity

- A Black Friday and the Spirit of Sharmila: Protest Art of North East India

- Ratan Parimoo: Paintings from the 1950s

- Mahendra Pandya's Show 'Kshudhit Pashan'

- Stunning Detours of Foam and Latex Lynda Benglis at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

- An Inspired Melange

- Soaked in Tranquility

- National Museum of Art, Osaka A Subterranean Design

- Cartier: "Les Must de Cartier"

- Delfina Entrecanales – 25 Years to Build a Legend

- Engaging Caricatures and Satires at the Metropolitan Museum

- The Mesmerizing World of Japanese Storytelling

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibiting Lyrical Visions: Paintings from North India

- Random Strokes

- Asia Week at New York

- Virtue of the Virtual

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, March – April 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Preview, April, 2012 – May, 2012

- In the News, April 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

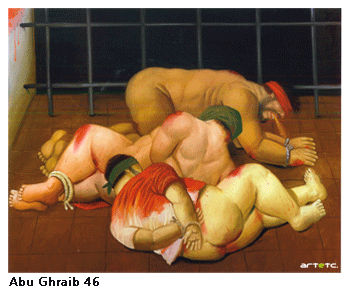

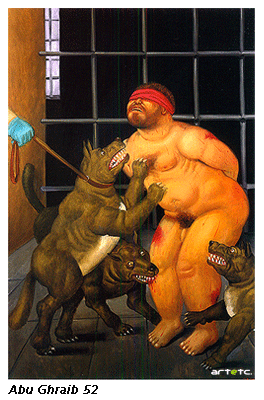

Fernando Botero's Grievous Depictions of Adversity at the Abu Ghraib

Issue No: 28 Month: 5 Year: 2012

by Preeti Kathuria

Son of a Colombian salesman, Fernando Botero lost his father when he was only two and this incident left a permanent mark of emptiness on his psyche. From the adolescent age of 13, he began to paint and draw scenes of bullfights. He had his first solo exhibition at the Leo Matiz Gallery, Bogota at the age of 19 where all the works were sold but this separation from his works left him unhappy. He then moved to Europe to study at the Academy of San Fernando, Madrid where he created work in the style of Velázquez and Goya. Later, he went to Italy to learn the fresco technique. He also studied Mexican muralist Diego Rivera closely. Botero moved to New York and won the Guggenheim National Prize for Colombia. His signature painting style of soft, well-rounded figures, so reminiscent of the Baroque master Rubens, developed in 1964. The success of his first important European exhibition at the 'Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden', in 1966 followed by Inflated Images at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1969, Botero established his reputation as a major international artist. The sudden death of his four-year old son in a car crash in 1970 added another agonising irk in his intensive artistic pursuit.

Son of a Colombian salesman, Fernando Botero lost his father when he was only two and this incident left a permanent mark of emptiness on his psyche. From the adolescent age of 13, he began to paint and draw scenes of bullfights. He had his first solo exhibition at the Leo Matiz Gallery, Bogota at the age of 19 where all the works were sold but this separation from his works left him unhappy. He then moved to Europe to study at the Academy of San Fernando, Madrid where he created work in the style of Velázquez and Goya. Later, he went to Italy to learn the fresco technique. He also studied Mexican muralist Diego Rivera closely. Botero moved to New York and won the Guggenheim National Prize for Colombia. His signature painting style of soft, well-rounded figures, so reminiscent of the Baroque master Rubens, developed in 1964. The success of his first important European exhibition at the 'Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden', in 1966 followed by Inflated Images at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1969, Botero established his reputation as a major international artist. The sudden death of his four-year old son in a car crash in 1970 added another agonising irk in his intensive artistic pursuit.

In 1973, Botero moved to Paris, where he produced his first sculptures. He then moved to Tuscany, in 1983 to revisit his childhood memories of painting bullfighting scenes. In the late 1990's he painted a series on the drug-fuelled wars of Columbia. “If they make an impression on the public, I have completed the mission of showing the absurdity of the violence”1, Botero said in an interview. Unwilling to make money out of depictions of people's suffering, he donated all the works to the National Museum of Colombia in 2003 saying that they rightfully belong there.

In 1973, Botero moved to Paris, where he produced his first sculptures. He then moved to Tuscany, in 1983 to revisit his childhood memories of painting bullfighting scenes. In the late 1990's he painted a series on the drug-fuelled wars of Columbia. “If they make an impression on the public, I have completed the mission of showing the absurdity of the violence”1, Botero said in an interview. Unwilling to make money out of depictions of people's suffering, he donated all the works to the National Museum of Colombia in 2003 saying that they rightfully belong there.

Botero once said, “In art, as long as you have ideas and think, you are bound to deform nature. Art is deformation…”2 Known worldwide for his voluptuous figurative paintings, Botero was driven by sheer anger and protest against the gruesome treatment with the inmates of the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Executed in oils, pencil and charcoal, he produced a series of fifty works and exhibited them in Italy and Germany in 2005. Horrific scenes of harassment, abuse and torture were intently visualized and painted by Botero when he read the newspaper reports. Depicting the ordeal of existence in the Abu Ghraib prison was Botero's prime motive. Hugely inspired by Picasso's masterpiece Guernica, Botero felt compelled to document the torture faced by Iraqi captives. His paintings show horrific details of nerve-racking brutality - a soldier beating up a prisoner with a baton, bleeding bodies of women attacked by dogs, soldiers urinating on blindfolded captives, mangled heap of naked bodies etc. His robust forms carried the radical yet inflammatory issue of post-war atrocity, with a lot of finesse. He thinks of himself as a chronicler, an annalyst just like Goya who through his works recorded the French atrocities in Spain.

Botero's corpulent figures have real weight yet they create a paradox with their robust energy and the less cavalier, almost tender, sometimes comic facial expressions; the well-nourished, plump hands of power are tied with ropes - this contrasting inventiveness creates a complex aesthetic and is deeply disturbing. The saturated, fleshy figures are ill-fed, ill-treated and are starved of any civility. A mawkish yet restrained dismissal seems to override most works.

Botero's bold pictorial rhetoric not only reflects his impulse and initiative to react against violence but also a sympathetic consciousness, a conviction to steer ahead uncompromisingly and create awareness on such episodes of fractured humanity. The artist holds no delusions that his paintings would reduce, curb or avert violence but they stand as testimonials to some gory, bloodstained, malevolent moments in history which can be avoided in the times to come. Botero says “They are works that will hang in a museum, so people can see their history.”3 Paradoxically, there are many who see these works as a tormenting re-visit, a rip-off of our healed wounds that stops us from moving on. But then art throughout history has reflected an obsessive continuity of social subject matter, seen as relevant and/or appropriate at the time of its production. The canvases become milestones, the layers of paint live-on, heralding research and different interpretations, as and when they inspire the practitioners of that age.

Botero's bold pictorial rhetoric not only reflects his impulse and initiative to react against violence but also a sympathetic consciousness, a conviction to steer ahead uncompromisingly and create awareness on such episodes of fractured humanity. The artist holds no delusions that his paintings would reduce, curb or avert violence but they stand as testimonials to some gory, bloodstained, malevolent moments in history which can be avoided in the times to come. Botero says “They are works that will hang in a museum, so people can see their history.”3 Paradoxically, there are many who see these works as a tormenting re-visit, a rip-off of our healed wounds that stops us from moving on. But then art throughout history has reflected an obsessive continuity of social subject matter, seen as relevant and/or appropriate at the time of its production. The canvases become milestones, the layers of paint live-on, heralding research and different interpretations, as and when they inspire the practitioners of that age.

Reference:

2)http://www.artincontext.org/exhibition/exhibition_additional.aspx?id=5310