- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Broot Force

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

Shoma Bhattacharjee in conversation with Rameshwar Broota.

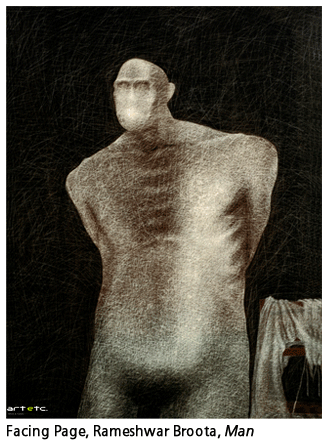

In Heart of Darkness, Kurtz exclaimed, 'the horror, the horror' with all the strength of his last remaining breath, his deathbed epitaph to the mess of humankind. The darkness, the vileness, pickling and complicating with age, also cast their inevitable shadows on the works of Rameshwar Broota. An interpreter of society, his evolving language used irony and satire, described as sharp and savage, as a vent for his anti-establishment views. Increasingly, he has attempted to unshackle himself from the directness and localization of commentary, settling into a more classical lexis, more powerful for its permanence.

In Heart of Darkness, Kurtz exclaimed, 'the horror, the horror' with all the strength of his last remaining breath, his deathbed epitaph to the mess of humankind. The darkness, the vileness, pickling and complicating with age, also cast their inevitable shadows on the works of Rameshwar Broota. An interpreter of society, his evolving language used irony and satire, described as sharp and savage, as a vent for his anti-establishment views. Increasingly, he has attempted to unshackle himself from the directness and localization of commentary, settling into a more classical lexis, more powerful for its permanence.

Shoma Bhattacharjee: 'I only paint when I have something to say,' that's something that you've gone on record with. In the last two years or so, there hasn't been any public viewing of your paintings.

Rameshwar Broota: It has been nearly a year and a half since I completed a large triptych, 70 by 210 inches, which I worked on for eleven months. It is true that I have nothing to say right now through this medium. I'm happy to let my photographs serve that purpose, that of self-expression. The pen-mouse is my brush or blade, the computer's large screen my canvas. It requires as much physical effort and mental involvement as brush and paint. When I face a blank canvas, I need to feel an urge. I cannot force myself, whatever the external pressures. You see, the soul and strength of a painting stand transparent. It cannot be faked. Tools and techniques, composition and colour can never take the place of inner imagination or conviction. I want to feel that way for my expression on canvas to be pure. I am not willing to compromise on the standards I have set for myself. Besides, why should I paint if I'm having such fun with photography?

SB: It is difficult to hold on to the hunger, which unknown, tends to creep away…

RB: It has to be a raw hunger. When I was young, I would experience it, that impulse to beat the odds. Any child does. This insatiable hunger would compel me to scribble, doodle, draw and paint almost throughout the day, eating into my study time. My parents would be exasperated. It was like forbidden fruit, which made my defiance something to be savoured. Often, I would resolve to get serious about my 'education', I would ceremoniously shut the door behind me and sit at my desk with the honest purpose of poring into my school books. But I would stray. I would be drawing cartoons in an economics class risking grave punishment! It was like someone within me was making me do those things. I was a mere instrument.

RB: It has to be a raw hunger. When I was young, I would experience it, that impulse to beat the odds. Any child does. This insatiable hunger would compel me to scribble, doodle, draw and paint almost throughout the day, eating into my study time. My parents would be exasperated. It was like forbidden fruit, which made my defiance something to be savoured. Often, I would resolve to get serious about my 'education', I would ceremoniously shut the door behind me and sit at my desk with the honest purpose of poring into my school books. But I would stray. I would be drawing cartoons in an economics class risking grave punishment! It was like someone within me was making me do those things. I was a mere instrument.

SB: An instrument…that's what I felt when I viewed your video, The Body. The elongated torso seemed like a helpless instrument at the mercy of an operator, a receptacle.

RB: The male nude, stripped of everything save muscle, bone, skin and posture, is immensely eloquent. I wanted to articulate its complexity by paring down my vocabulary to the barest minimum. After working with large detailed figures, I graduated to tiny ones and ultimately to just structures and textures that suggested the presence of humanity. I called them Traces of Man or Scripted in Time.

SB: Meanwhile, your photographs speak quietly, richly.

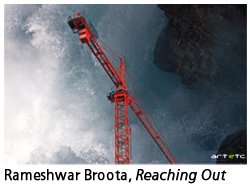

RB: It is too complex an act to simply just fill in the blanks between paintings. I end my day at 2 am most of the days. It wholly absorbs me. When I'm painting, I can do some photography related work on the side. But when I am concentrating on photography, I cannot paint. It demands that degree of immersion. I am delighted, even uplifted, contextualizing, re-contextualizing a photograph, coaxing my point of view into a simple snap of a gray block of concrete buildings, or a brick and mortar wall. The physical shot itself is just ten per cent of the final frame. The actual creative work starts in the darkroom or the computer. At the same time, it is not a manipulative act, as one has to remain honest to the laws of photography.

SB: Do you work in the old-fashioned way at all these days?

RB: I had my own darkroom and acid baths. The enlarger is still there somewhere. But in the last 12-13 years, I've got all my tools in the hardware and software of modern technology. Also, there's no end to upgrades in technology, which serves my purpose perfectly. It's difficult not to look back with wonder at the change…the age of contact prints and doing the rounds of neighbourhood studios, of days wasted in futile quest of right colours and textures, those days of utter frustration. Now, I'm happy to have the controls in my hands so I can implement my concepts seamlessly. I take full advantage of the scope for experimentation, of doing and undoing till I get it right.

SB: Are you a gadget person?

RB: Only in so far as I can get my work done through these gadgets.

SB: On a lighter vein, do you ever lapse into plain picture-taking? Give into the temptation of clicking family members or the pretty stage that Nature provides? Just to give yourself a break…

RB: There has to be an expression or an element of mystery. I cannot take sweet shots, might as well offer a gulab jamun! Seriously, I may want to take your photograph because I find your posture (imitating my somewhat crouched self) curious, as it may convey something about you that you're unconscious of. I had taken a photograph of my wife asleep in bed as I found the aloofness of her prone body in a sprawl of sheets very arresting. I layered this image with another picture of a plane bisecting the sky with its trail of smoke, and called it No Mouse, No Elephant…to convey a sense of detachment, almost dream-like. So, even if I do take so-called random shots, ultimately I strive to make something of my own out of them.

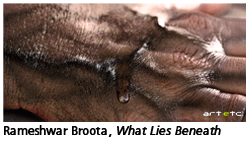

SB: As in your paintings, the co-existence of angularities, both organic and mechanical, or the co-existence of hard edges and mellower surfaces, is there in your photographs. The feeling of seeping into unknown viscera is particularly intense in What Lies Beneath I, where a single magnified drip of water provides a soft break in an unrelenting skin-scape of fine, sharp lines and chorded veins.

SB: As in your paintings, the co-existence of angularities, both organic and mechanical, or the co-existence of hard edges and mellower surfaces, is there in your photographs. The feeling of seeping into unknown viscera is particularly intense in What Lies Beneath I, where a single magnified drip of water provides a soft break in an unrelenting skin-scape of fine, sharp lines and chorded veins.

RB: I want to go to spaces that are unseen, unknown, the so-called unconscious. But, the conscious and the unconscious exist side by side for me. When something happens or unfurls on the surface, it may seem accidental, but in reality, it has been cooking just beneath for a long time. As in Nature, nothing is an accident for me. The technique that I use for my paintings of layering paint and then using sharp blades to scratch the various surfaces to create forms may seem to have been arrived at accidentally one fine day when I defaced a painting with thick green varnish paint, and then restless for results, impatiently started scratching on the still-wet surface with a knife. But it wasn't really an accident. I was constantly thinking of, aiming for, a certain texture, employing various known techniques in different ways, creating forms. My 'discovery' was simply a maturing of my toil and the visuals already pre-existent in my mind.

SB: You have gradually moved away from comment-based works…

RB: I realized that the directness of social commentary and satire was diluting the aesthetics of my work, making them localized, locking them up in personal circumstances and imageries. I wanted to free myself and my art from the bony laborers and the apes. I felt drawn to the stripped down male body, which packed in vulnerability and vitality, simplicity and complexity. I felt I could persuade this less-feted at least artistically so half of humanity to speak my minimal, universal language. The clever verses of a ghazal have their appeal, but pales before the depth of classical music, where a single line may be repeated endlessly but the resonances are so permanent.

It's easy to drop into comfortable habit. My black works found a lot of acceptance here and abroad. However, I found myself getting more drawn towards stark and simple shapes cutting into vast white, featureless spaces.

SB: The starkness of Between the Lines is reminiscent of Antonioni's stainless urban streets, which he often recreated to suit his vision.

RB: Maybe.

SB: Are you a film watcher?

RB: Not really. I like watching Hindi films off and on but that's about it. I feel helpless simply trying to keep up with the frames of motion pictures. Actually, I can't help myself from painstakingly breaking down a single frame into all the million elements that go into making it. It's just a fleeting moment in the film but there is so much detail and thought that have gone into a solitary moment, that's what straightaway involves me. Even if I consider just the visuals, I lose myself in the details of sets, movements, lights, editing, especially the editing. I get so absorbed that I miss out on the dialogue, the narrative. If I try focusing on the dialogue, I miss out on the nuances of the acting, the expressions. There's so much to grasp in the continuous movement. Everything goes into making it complete. Every corner, every inch counts.

SB: Are there any photographers you are drawn to?

RB:There are many photographs that draw me, and maybe I draw inspiration from them. Rather, I keep absorbing them.