- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

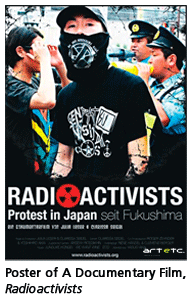

The documentary film Radioactivists made in 2011 is a big move that can be regarded as a live picture of ‘protest art’ in the new millennium by two young female filmmakers from Germany who took the initiative to capture the protest movement in Tokyo against nuclear war comprising a cumulative voice of the Japanese protest culture. Julia Leser and Clarissa Seidel have worked on this project for months in the last year and Sarmistha Maiti on behalf of Art Etc. news & views takes the opportunity to have an intense discussion with one of the filmmakers, Julia Leser, about the film and its making and how it has been a vital force to popularize the protest movement in Japan…

The film encapsulates a live demonstration of the protest marches/movements that have taken place in Tokyo during May-June 2011 where individuals, groups, social organizations active in voicing against the nuclear ventures that are risking mass life in Japan in several ways. Though the protest culture specifically against this issue was not new but after the events of 11th March, 2011 things took a radical shape mobilizing the movement further and making it a global political, environmental and human issue. The filmmakers not only captured the demonstrations and the protests but picked up individuals and active organizations, like the Citizen's Nuclear Information Center, a Japanese NGO that has been informing about the risks of nuclear power for more than 30 years. The main protagonist of the film Shiroto no ran, or 'Amateur's revolt', which is not a political organization, but a group of friends and mostly shopkeepers of recycle and second-hand shops in Koenji, Tokyo was found out in the process of filming itself and that is how the documentary got its common man’s overview and perception of this whole movement instead of just theorization of issues on political benches. The prime target of the filmmakers was to give this protest a complete face and speak from the ground level of action. So, the social and political scientists and intellectuals formed the connecting thread throughout the film to reflect the magnitude of the protests. The film in a nutshell is a document of the spirit of the protest movement in Japan deciphering the challenges and triumphs of historical significance.

The film encapsulates a live demonstration of the protest marches/movements that have taken place in Tokyo during May-June 2011 where individuals, groups, social organizations active in voicing against the nuclear ventures that are risking mass life in Japan in several ways. Though the protest culture specifically against this issue was not new but after the events of 11th March, 2011 things took a radical shape mobilizing the movement further and making it a global political, environmental and human issue. The filmmakers not only captured the demonstrations and the protests but picked up individuals and active organizations, like the Citizen's Nuclear Information Center, a Japanese NGO that has been informing about the risks of nuclear power for more than 30 years. The main protagonist of the film Shiroto no ran, or 'Amateur's revolt', which is not a political organization, but a group of friends and mostly shopkeepers of recycle and second-hand shops in Koenji, Tokyo was found out in the process of filming itself and that is how the documentary got its common man’s overview and perception of this whole movement instead of just theorization of issues on political benches. The prime target of the filmmakers was to give this protest a complete face and speak from the ground level of action. So, the social and political scientists and intellectuals formed the connecting thread throughout the film to reflect the magnitude of the protests. The film in a nutshell is a document of the spirit of the protest movement in Japan deciphering the challenges and triumphs of historical significance.

Sarmistha Maiti: What is the concept of the film Radioactivists and how is it related to the Japanese context in the present century?

Julia Leser: With Radioactivists we decided to make a film about the protest movement which started in Tokyo after the events of 3/11. In Japan, big demonstrations have not taken place for a few decades. There have been student revolts and powerful social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, but since then demonstrations decayed rapidly for various reasons: First of all, the political radicalization of protests in the 70s resulted in a demo-allergy, since the majority of the Japanese people started to associate demonstrations with violence and political ideologies like communism, socialism, Marxism etc. Another reason for the decay of protests in Japan lies within the Japanese social structure itself. In Japan, voicing your opinion in public is not a common thing to do. In order to respect the other people, an individual does not voice his/her political opinions in public.

Julia Leser: With Radioactivists we decided to make a film about the protest movement which started in Tokyo after the events of 3/11. In Japan, big demonstrations have not taken place for a few decades. There have been student revolts and powerful social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, but since then demonstrations decayed rapidly for various reasons: First of all, the political radicalization of protests in the 70s resulted in a demo-allergy, since the majority of the Japanese people started to associate demonstrations with violence and political ideologies like communism, socialism, Marxism etc. Another reason for the decay of protests in Japan lies within the Japanese social structure itself. In Japan, voicing your opinion in public is not a common thing to do. In order to respect the other people, an individual does not voice his/her political opinions in public.

But we felt, that this is about to change now. Since 3/11, especially since the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident, people all over Japan started participating in grassroot demonstrations, voicing their anger against TEPCO, the media, and the government, and connecting the events of 3/11 with issues related to the life and work- environment in Japan. We wanted to listen to the protagonists of this new and interesting movement, and we wanted to show with our film, how active and eager these people are to make change in Japanese politics and society.

SM: The aftermath of Second World War is still borne by the people of Japan. How easy as filmmakers from outside Japan was it to understand and approach this issue and what were the key perspectives that you followed overall in bringing the film into shape?

JL: We felt that it was difficult for the (international) media to report about what was going on after 3/11 and to approach the developments due to a lack of background knowledge and language barriers. In Germany, for example, the news of 2000 people participating in an anti-nuclear demo in Tokyo did not leave any impact, because a lot of information and background knowledge about the Japanese protest culture was missing. Therefore, people reading the news here thought “Ok, 2000 people is not a lot, why are Japanese people so stoic in this situation?”, because they could not know how important such an event really is in Japan, and that 2000 people demonstrating means that something very important is going on.

But I, Julia, have been studying Japanese Studies for a while and knew a lot about the Japanese post-war history and the Japanese protest culture. So Clarissa and I made an outline about what we wanted to say in our film and how we wanted to say it. We contacted the Japanese social scientist Yoshitaka Mori, and asked him about the history of protest movements and how the events of 3/11 were a historical turning point in Japanese post-war history. We met the political scientist Chigaya Kinoshita, because we wanted him to talk about the 'iron triangle' of Japanese media, corporations and government. The philosopher Yoshihiko Ikegami told us, why Japan ended up with 54 reactors after the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He told us about the brainwashing of Japanese government and media to propagate nuclear power.

We are very lucky to have these three people in our film, to frame our main topic – the protest movement after 3/11 – with the necessary background knowledge, so everybody who sees the film can understand the core developments that made the Fukushima accident and the resulting demonstrations even possible. That was very important to us.

SM: What was the course of journey from the pre-production stage to the post- production stage in giving the final shape to the film?

JL: The whole idea of making a film came very spontaneous. On March 11, 2011, when – to our very surprise – the earthquake hit, Clarissa just graduated from university a couple of months ago and I, Julia, was still just a student of Japanese Studies, spending a year abroad in Tokyo. Both of us have always been interested in film and photography, but we never planned to make a 'real' film together before. We left Japan 2 days after the earthquake, and followed the news from Germany. Then we heard of the first anti-nuclear demonstrations taking place in Japan. We were positively surprised and instantly became aware of the fact, that those were very important events! We wanted to return to Japan and see those demonstrations with our own eyes, and then we had the idea of making a documentary about it. That was just about 2 weeks before we started shooting in Tokyo. In those two weeks we bought the camera, microphone and recording device, contacted the people we wanted to interview and set up a (very) rough concept for the film. We returned to Japan by the end of April 2011 and filmed day and night for about 3 weeks. Clarissa left Japan and started editing in Germany. By the beginning of July 2011, the film was finished and we had our first screenings in Tokyo.

JL: The whole idea of making a film came very spontaneous. On March 11, 2011, when – to our very surprise – the earthquake hit, Clarissa just graduated from university a couple of months ago and I, Julia, was still just a student of Japanese Studies, spending a year abroad in Tokyo. Both of us have always been interested in film and photography, but we never planned to make a 'real' film together before. We left Japan 2 days after the earthquake, and followed the news from Germany. Then we heard of the first anti-nuclear demonstrations taking place in Japan. We were positively surprised and instantly became aware of the fact, that those were very important events! We wanted to return to Japan and see those demonstrations with our own eyes, and then we had the idea of making a documentary about it. That was just about 2 weeks before we started shooting in Tokyo. In those two weeks we bought the camera, microphone and recording device, contacted the people we wanted to interview and set up a (very) rough concept for the film. We returned to Japan by the end of April 2011 and filmed day and night for about 3 weeks. Clarissa left Japan and started editing in Germany. By the beginning of July 2011, the film was finished and we had our first screenings in Tokyo.

What we wanted to say with our film was obvious from the beginning to the end of the whole production. Of course, as far as our filming proceeded, we got in touch with new information and interesting people that we wanted to include in our project as well, like the Human Recovery Project. In the editing phase, we noticed that some images were missing that could illustrate some of our messages, so even after Clarissa left Japan, I continued shooting demonstrations and sometimes elevators, sent her the material and she included these scenes in our film.

SM: What is this anti-nuclear protest all about? Briefly describe how and why it had started and what is the discourse your film has attempted to project regarding this movement?

JL: This anti-nuclear protest is not only about the risks of nuclear power plants, it is also addressing other issues which relate to the politics and society in Japan in general. It is addressing the late capitalism and consumerism and the issues of high consumption of energy in Japan related to it. It is addressing the Japanese life and work environment, like the issue of part-time workers who are mostly subcontracted to work in nuclear power plants without sufficient training or protection against radiation. This protest appeals for a change of those conditions that made Fukushima as a man-made disaster possible, and it appeals for a change of lifestyle: The social scientist Yoshitaka Mori said that the Japanese people should stop pursuing wealth and effectiveness, but pacing themselves and seek another way of living by – as a first step – using less energy.

The activists we accompanied for several weeks are aware, that now is the moment to fight for a change in the awareness of all those issues in Japanese politics and society. And we as filmmakers felt truly inspired by those attempts.

SM: The protest march that is held every week and so many people who flood in to be a part of it…from there, how did you select the protagonists of your film?

JL: In the focus of our film is Shiroto no ran, or 'Amateur's revolt'. I have known this group of people since 2008, and have been interested in their actions and philosophies. Shiroto no ran is not a political organization, but a group of friends and mostly shopkeepers of recycle and second-hand shops in Koenji, Tokyo. Most of them have a precarious background, working part-time. All of them have agreed to problematize the Japanese capitalism and society by direct action: In forming the community Shiroto no ran, selling second-hand goods, working and hanging out together, organizing info events, workshops and demonstrations, they clearly try to oppose the mainstream capitalist society. In Shiroto no ran, we saw a lot potential for making changes and this huge pool of ideas and creativity, so we decided to make them one of our protagonists in our film. Especially since it was Shiroto no ran who started organizing the first big demonstrations in April and every month from then on, gathering ten thousands of people every time.

SM: Protest through art is gaining mass popularity day by day. Your film has been mostly acknowledged in this category. How do you opine for it?

JL: We think that protest art is the future (and in Japan, the present) of gaining mass popularity. One of the reasons a lot of people feel attracted by the Japanese anti-nuclear demonstrations is that those are mostly 'sound demos', which means that you will find a lot of music, a lot of designs, performances and artists in those demos, all of which creates a kind of festive atmosphere.

Moreover, anti-nuclear artists gain more and more attention in Japan and internationally as well, like Chim Pom or Illcommonz. They deal with the issue of Fukushima in a very creative and sometimes provocative way, they do guerilla performances in train stations and set up video installations in galleries. Over the past year, their art has been widely recognized and by that, they also help popularizing and spreading the anti-nuclear attitude. This is a new and interesting development (not only) in Japanese protest culture.

SM: The political and social fight in Japan against its government has begun and people are profusely becoming a part of it. How efficiently your film could penetrate the mass psychology as a whole voicing this movement?

JL: Since we filmed in April and May 2011, we captured just the beginning of this new movement – the first successes of the demonstrations as well as the anxiety and the obstacles the activists had to face and cope with everyday. It is exciting and thrilling to see how the amount of people participating in the movement grows and grows, but on the other hand you start to acknowledge that this fight, which has just begun, will be a long and difficult one as well. Nonetheless, Radioactivists is an important snapshot in time, and people who see it often feel inspired by the Japanese activists' efforts.

SM: Last but not the least, what inspired you to take up this project? Add director’s statement as a footnote of this interview. Also state how as female filmmakers, the people reacted while you were filming such a public issue.

JL: As written before, what inspired us the most is the vigorous endeavour of the Japanese activists, especially Shiroto no ran. Another reason that inspired us to take up this project is the way the (German) media covered the events of post-3/11, stereotyping the Japanese people due to the lack of background knowledge. We wanted to oppose those media reports with a documentary that shows 'the other side' of dealing with the events of Fukushima in the changing Japanese society.

Image Courtesy: Julia Leser and Clarissa Seidel