- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

When Protest Erupts into Imagery

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Rita Datta

14 March, 2007. This date may well come to be regarded by researchers as some sort of a turning point in the recent history of Bengal, and, tangentially, of India. That was the day Nandigram erupted into a cause. Nobody at that stage had gauged its significance. If the ruling coalition congratulated itself on its small gain in terms of turf recovered, it could not anticipate the crucial turf lost: the culture-minded CM’s honeymoon with a valued constituency, middle class intellectuals, who would have an important contribution to make a change of guard at Writers’.

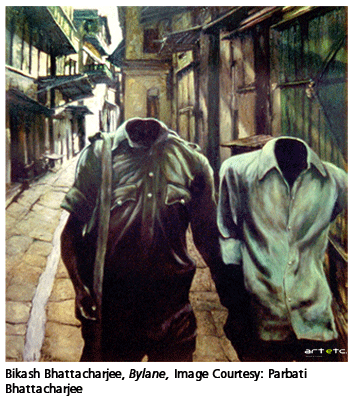

Many artists, writers, and theatre activists who’d grown up under Congress rule, had quite naturally drifted to Left politics, especially during the Naxalite upsurge and the Emergency. Particularly because of the way the Siddhartha Ray regime had dealt with the public, it not only arrested Naxalites but also innocent young sympathisers. That was the time Bikash Bhattacharjee’s humanist concerns were jolted as much by the State’s abuse of power as by the media’s competitive hunger. Two of his works, Homage To…. and Interview would be regarded as a most unforgiving criticism of both. So the Left was the right choice, then.

Many artists, writers, and theatre activists who’d grown up under Congress rule, had quite naturally drifted to Left politics, especially during the Naxalite upsurge and the Emergency. Particularly because of the way the Siddhartha Ray regime had dealt with the public, it not only arrested Naxalites but also innocent young sympathisers. That was the time Bikash Bhattacharjee’s humanist concerns were jolted as much by the State’s abuse of power as by the media’s competitive hunger. Two of his works, Homage To…. and Interview would be regarded as a most unforgiving criticism of both. So the Left was the right choice, then.

But power comes with its own in-built nemesis and the Left imperceptibly took on the mantle of the Right as the new anti-Establishment emerged. And Nandigram, completing what the resistance of farmers in Singur had begun, quickly lent a symbolic charge to the protest which began as a condemnation of injustice but gathered steam until it swelled into a call for change.

Jogen Chowdhury and Shuvaprasanna were two of the artists who’d become disillusioned with the Left at that point. Interestingly, if Chowdhury had aquired his voice of protest early in his career, it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that the latter had had it thrust upon him by Nandigram and Singur. The involvement of many of Calcutta’s restive creative minds in the post-Nandigram conflict gave to this protest an entirely new dimension, a sharp edge. Legitimate expressions of discontent—processions, slogans, strikes, marches, pamphlets—raise public awareness and political temperatures. But protest acquires depth when it is consecrated in long-term memory through the arts.

The most shocking mayhem in war and riots generally descends to footnote statistics unless there’s an iconic chronicler like Picasso who can reinvent the trauma and agony of victims in a small Basque village called Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. On the other hand, the horror of a war crime might forever be captured by a satiric tongue as by American author Philip Roth who, in his book Our Gang, used the My Lai massacre in Vietnam to lambast the Nixon-Agnew team and its pontification on traditional family values. Nixon in a speech had declared his opposition to abortion. Abortion, he’d proclaimed, went against the right of the unborn. So, argued Roth’s voice in the book, when unarmed women and children were killed in the Vietnamese village by American soldiers, it could have caused a moral dilemma in Tricky Dick (the name for Nixon in the book) if any of the women happened to be pregnant, amounting to an infringement of the right of the unborn!

But protest may not always be triggered by an event. A great stimulus for the arts has always been the misfit’s or the thinking critic’s gesture of rejection of the dominant socio-economic system of his own culture. Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times is not less of a protest of industrial capitalism for being a fun film that children enjoy. On the other hand, the rejection could be of populist politics. Tagore’s Chaar Adhyay and Gharey Bairey were, at one level, clearly political, and as clear in their tone of protest against extremism. And sometimes, protest can swell into a whole movement which is what Dadaism—and, to an extent, Surrealism—was, having sprung out of the nihilism of a disillusioned generation in inter-war Europe.

When we look at the two artists we are discussing, we can see that, while Shuvaprasanna belongs to the former category, Chowdhury belongs to the latter. That is, Chowdhury, brutally yanked from his idyllic life as the zamindar’s little son in Faridpur, East Bengal, by Partition, and thrown at the bottom of the social ladder in an alien and uncaring city, Calcutta—where the family’s only identity was as uprooted refugees—would grow up in circumstances that wouldn’t cocoon his sensibility from the real and the unsavoury. Thus, it wasn’t so much a particular event, Partition, as the experience of its aftermath that seems to have oriented his sympathies, his humanist ideals, his very vision in art. To somebody who’d actually lived through the horror of being suddenly displaced, stable life inexplicably lost to new struggles, Nature’s beauty and bounty replaced by an ugly urban ethos, tears become irrelevant; satire takes over. Badinage becomes the weapon to prick the pompous; brash camp a language of subversion.

When we look at the two artists we are discussing, we can see that, while Shuvaprasanna belongs to the former category, Chowdhury belongs to the latter. That is, Chowdhury, brutally yanked from his idyllic life as the zamindar’s little son in Faridpur, East Bengal, by Partition, and thrown at the bottom of the social ladder in an alien and uncaring city, Calcutta—where the family’s only identity was as uprooted refugees—would grow up in circumstances that wouldn’t cocoon his sensibility from the real and the unsavoury. Thus, it wasn’t so much a particular event, Partition, as the experience of its aftermath that seems to have oriented his sympathies, his humanist ideals, his very vision in art. To somebody who’d actually lived through the horror of being suddenly displaced, stable life inexplicably lost to new struggles, Nature’s beauty and bounty replaced by an ugly urban ethos, tears become irrelevant; satire takes over. Badinage becomes the weapon to prick the pompous; brash camp a language of subversion.

With an elder brother in the Communist Party, faith in a red dawn had awoken in Chowdhury, too, though it turned out to be only a passing phase. It is now well known that when, as an art student, he didn’t have the money to buy canvas and paint, he used newsprint, ink and pastel. And because there was no electricity at home, his pictures came to be dominated by black. He can now clearly relate the close cross-hatchings that marked his early work to a deep sense of restless frustration that had afflicted him during that difficult period. Tracing the circumstances that shaped his concerns indicates why he has always been sensitive to causes. Whether it is the post-Godhra killings, Abu Ghraib or Nandigram. Indeed, several years before Singur and Nandigram entered everyman’s political lexicon, there were Keshpur and Garbeta, which found their way into Chowdhury’s art. Gujarat, 2002, would haunt him with its horror stories. Of which, the attack on a pregnant woman, whose stomach was split open and the foetus wrenched out, was to surface in a serigraph of chilling understatement called, simply, The Unborn Child. And a prone figure in dry pastel, the face webbed with textured lines, spoke out against the prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. In fact, open gashes, stitched faces and cracked skulls have recurred in his recent figures as quietly articulate marks of violence. But the strategy has been to depict them dispassionately, aseptically, almost clinically, drained of blood and gore, of overheated emotions, which makes the images more insidiously brutal.

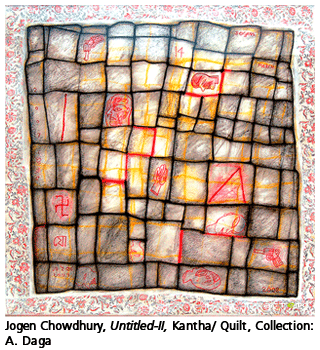

And so, it wasn’t at all surprising to find the frustrated idealist in the thick of the post-Nandigram battle for ‘parivartan’. His response to the Nandigram violence was probably first seen at Aakriti Art Gallery in 2008 in a work that was, significantly, untitled. As though to say that he had nothing to say. Its muted tone, its stunned absence of emotion, the patchwork quilt effect with scraps of handmade paper—recalling the domestic craft with recycled cloth, common among village women—combine to enhance the shock of the image: decapitated heads, coldly displayed, along with a swastika and guns. There’s a pretty floral border that frames it as a kind of ironical aside. A year later, at a Cima show in December, 2009, he quoted disturbing images from Singur and Nandigram. He called this work Hirak Rajar Deshe, which insinuated both the whimsical tyranny of the film’s king and its Eisensteinian sequence when his statue is pulled down. Soon, Jangalmahal would also invade his conscience and his art which sought to remind viewers that it was in a sylvan Eden that hell had come to reside….

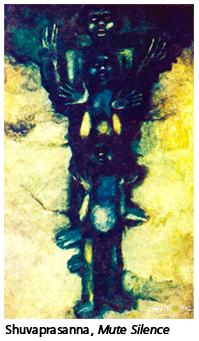

Unlike Chowdhury, there was no sudden disruption in the life of Shuvaprasanna. Hence, protest per se wasn’t to burst forth so readily in him. His romantic imagination dwelt more on man’s inner turmoil for he was, he says, not exactly an extrovert. And that is reflected in his art: portraits, animals, birds, especially the owl, along with cityscapes, were frequent subjects. However, like any sensitive youngster, the dark underbelly of the city, the precarious life of its poor and the palpable injustice of the system, couldn’t but bother him, as it did many, many young people who turned to the political extremism that’s been labelled the Naxalite movement. The artist’s social concern becomes apparent in very early works like Lament (1971), and The Witness (1972), with brooding colours evoking the marginalised. The Bangladesh struggle soured his creative mood, too, with more burnt sienna in his palette, the sky in his paintings turning dull and the moon turning mournfully pale. “Like a Hindu widow’s dress”, says the artist. The passing years earned him success and fame, but that wouldn’t dull his humanist core for A Play, done in 1993, indicts the society that consigns its children to the very brink of existence.

In those days, such works would immediately be thought of as Leftist in terms of their emotional accent, though the artist wasn’t involved in any political activity. Neither was any overt political sympathy revealed. It was really Nandigram, he confesses, that had drawn out his voice of unambiguous, even strident protest. In two shows in Calcutta in 2011, several works with specific political messages were seen. The Shadow, for example, seems to carry a not very veiled reference to the Netai incident. The sentient tree in the foreground, bare branches splayed like grasping tentacles, stresses the vulnerability of the figures. He’s also used helpless hands in a few works as a telling motif in recent years.

But with Agenda No-mmxi for Right Decision he decided to hit at the solar plexus of the CPM by identifying, in a sharply caricatured manner, its leaders, all without their left arms, possibly to suggest that the party had lost its Leftist ideals. Nor was the former Chief Minister spared. And yet, perhaps not surprisingly, Shuvaprasanna was once quite close to Buddhadev Bhattacharjee, as were many other creative and intellectual people of the State. But neither considerations of civility nor of practical gain could deter the artist once his rage was stoked by the painful human tragedy at Nandigram and Singur.

Art is, has to be, contextual, though often obliquely so. What doesn’t wither with age or stale with custom, is renewed in meaning through fresh interpretations, when the immediate context recedes into history. But analogies that are too closely related to events and causes, do stamp a topical best-use-before date on art and may render it dated in changed circumstances. While Shuvaprasanna has indeed allowed his anger to spill over in works like Red Terror, Agenda (named above) and 30 Years in Power, works like his Mute Silence (1971) simmer with the kind of inchoate despair that, ingrained in the human situation, can hardly atrophy with changed circumstances. Jogen Chowdhury, on the other hand, reacts to contemporary events but turns the images anonymous, not only bereft of identity but also torn from the context that fuelled them. Hence, Abu Ghraib will remain as relevant as those battered heads and lacerated bodies bearing names like Dead, Victim and Wounded.

Art is, has to be, contextual, though often obliquely so. What doesn’t wither with age or stale with custom, is renewed in meaning through fresh interpretations, when the immediate context recedes into history. But analogies that are too closely related to events and causes, do stamp a topical best-use-before date on art and may render it dated in changed circumstances. While Shuvaprasanna has indeed allowed his anger to spill over in works like Red Terror, Agenda (named above) and 30 Years in Power, works like his Mute Silence (1971) simmer with the kind of inchoate despair that, ingrained in the human situation, can hardly atrophy with changed circumstances. Jogen Chowdhury, on the other hand, reacts to contemporary events but turns the images anonymous, not only bereft of identity but also torn from the context that fuelled them. Hence, Abu Ghraib will remain as relevant as those battered heads and lacerated bodies bearing names like Dead, Victim and Wounded.

That will always suggest that man, after all, is a wounded victim. Not so much of a political party as of life.