- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Abhijit Gupta

Having to write about a group of shows held nearly three years ago as a contribution to an issue dealing with Protest Art throws up many challenges and an invitation to play the devil's advocate. I will not attempt to write a review; I am not qualified for that task. This could be a postmortem that will attempt to investigate some core issues seen in relation to Protest Art. However, I must hasten to add that pertinent questions were debated then and much had remained unanswered. I share some of these with you now. Validate them or trash them, but the fact remains that the merits of Art Against Terrorism as an event continues to demand our attention.

Having to write about a group of shows held nearly three years ago as a contribution to an issue dealing with Protest Art throws up many challenges and an invitation to play the devil's advocate. I will not attempt to write a review; I am not qualified for that task. This could be a postmortem that will attempt to investigate some core issues seen in relation to Protest Art. However, I must hasten to add that pertinent questions were debated then and much had remained unanswered. I share some of these with you now. Validate them or trash them, but the fact remains that the merits of Art Against Terrorism as an event continues to demand our attention.

The spate of terrorist strikes in India and the outrageous attacks in Mumbai were reason enough to warrant a collective protest and that is exactly what Art Against Terrorism attempted to do. At the outset, I must admit that such a show of solidarity by various galleries, exemplified by working together was no doubt very encouraging, raising the expectation for more such events in the future.

“The use of the middle word in our title pre-defines a position,” wrote Ruma Dasgupta in her catalogue essay on the exhibition. The title indeed located the 117 artists participating in the nine shows that were held between March and April of 2009, within the boundaries of a discourse that underlined their indignation against acts of terrorism, translated into a display of collective protestation by artists and galleries. But did it? The answer will perhaps become evident in due course.

Let us first examine the fundamentals of the term Protest Art and when any art activity qualifies to be labelled so. Firstly, the term is used broadly to classify art that addresses and/or supports protest movements against perceived injustices. The operative word here is 'movement' and this show of solidarity by artists can by no stretch of imagination be labelled that, as it lacks that continuity in time and location for it to become a 'movement'. Secondly, Protest Art employs a variety of methods that are easily visible to the public and/or involves public participation rather than be confined within the white cube. This, however, is by no means an indictment of the intentions of the participating artists and galleries it is a debate that this group of exhibitions generated. The debate therefore revolves around a central concern: was the platform of protest appropriate? Can such protests in sanitized environs have the same impact as a demonstration of public outrage out on the streets? Did these shows succeed in increasing awareness or add to the public 'connect' which such a threat perception demands? I frankly have no clear answers and loathe going polemical. Therefore, I will not dwell on them as this is not the appropriate forum, and they would be best dealt within a participatory atmosphere. The questions remain nevertheless.

The fact that Protest Art presumes the existence of an activist temperament in its practitioners leads one to believe that it is qualified by a certain level of long-term commitment to a cause and therefore is a culmination of thought, emotion and action. The reasons for an event like Art Against Terrorism existed then and still exist now, but in public memory ephemeral as it is the consequences of such a short life-span demands repeated reminders. If that had happened on a collective or even on an individual level in essence it would have been considered activism and qualified as Protest Art. Therefore a protest that only registers a flash in the pan has its obvious limitations towards claiming a generic label. I know some of you will scream Guernica at me, but aren't those exceptions to the rule?

So how does one categorize this slew of shows under the common moniker of 'Art Against Terrorism'? Exactly that a group of shows titled Art Against Terrorism. Does that in any way take away the fact that it was a valid form of protest? I guess not. But, the term 'Protest Art' is suggestive of being part of a 'movement' that does not allow for smug and fashionable trivialization.

With that out of the way, allow me to indulge in a bit of semantics. The term 'terrorism' has been defined in varied ways. Ruma Dasgupta in her aforementioned essay quotes the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Politics which states that “one person's terrorist is another person's freedom fighter” a view in a way echoed by Charles Chaplin in his film Monsieur Verdoux. I quote, “One murder makes a villain, millions a hero, numbers sanctify”, or as Voltaire said, “It is forbidden to kill; therefore all murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets”.

Pranab Ranjan Ray in his introductory catalogue essay draws distinctions between state and non-state players, debunking the notion of 'state sponsored terrorism' and supporting Thomas Hobbes' view that “the State legitimately enjoys the power of coercion”. The difference being that non-state players do not remain on the scene after the mayhem is committed, whereas the state remains present on the scene to witness (and perhaps gloat at) the effects of its power. Legitimate power of coercion? Why do we then protest injustices perpetrated by the state if such acts are legitimate? Don't acts of civil disobedience against the state employ Protest Art as a potent tool? Doesn't the word 'terrorism' suggest the act of terrorizing and instilling fear and dread? I am yet to come across an acceptable and sustainable argument. Therefore the questions remain.

There are many other views that may be discussed, but that needs another forum. Whatever be the opinions propounded, the final intent here is to examine how artists responded to the central theme of this somewhat 'curated protest'. Looking back, one is obliged to notice that a host of other agendas both personal and public were at play. The spate of terrorist strikes in India the chief reason for this collective show of indignation was dealt with aptly by some of the artists, while others chose to give vent to personal grievances ranging from petty partisan posturing to other sundry and trivial issues. That was their prerogative as artists; no one can take that away from them.

The works that demanded our attention ranged from the sentimental to the poignant, from the vociferous to the subtle, from the grave to the flippant. Some even questioned the basic premise of the motion, as reflected in “one person's terrorist is another person's freedom fighter”. Artists displayed a motley range of understanding of the issues involved, even to the extent of being politically incorrect in a few stray cases. One also noticed quite a few works as signature pieces that alluded to terrorism in the most oblique way. Red being the colour of life-blood, not just bloodshed, needs to be objectified and referenced to drive home the connection with terror; otherwise it flounders in aesthetic waters.

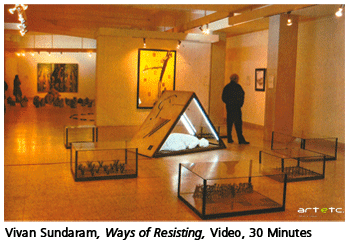

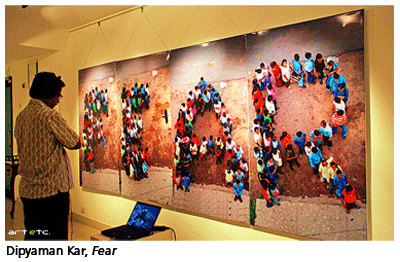

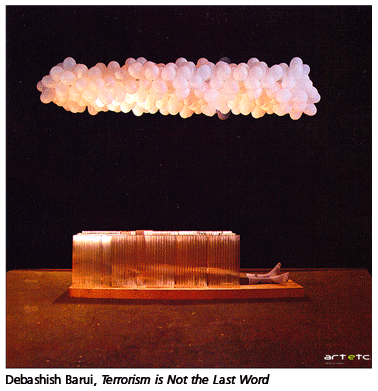

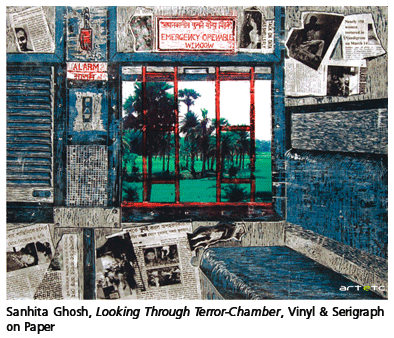

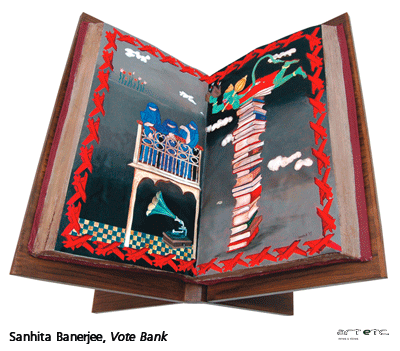

What seemed to be significant though was that the artists negotiated a gamut of explorations on the psyche of fear. I cannot do justice to all the participating artists in this short space and will thus mention only a few as examples. One such work that stood out for its starkness was Fear by Dipyaman Kar. Another work that deserves mention for its appropriateness was the video-installation Nine to 99 by Chhatrapati Dutta. Sanhita Banerjee's tongue-in-cheek Vote Bank contrasted with the gravitas of Sanhita Ghosh's Looking Through Terror Chamber. Aditya Basak's video of candle flames and Manjari Chakraborty's Candles 1 & 2 were both silently poignant. In GR Iranna's work Morning Prayer Occupation one could almost hear the crunch of military boots, questioning the repressive power of the State. Debanjan Roy's untitled installation of a non-existent Gandhi under guard was eloquent as was Prabir Gupta's Testimony I Had to Feed My Family. Vivan Sundaram's involved installation Ways of Resisting and Binu Bhaskar's Mask were both chilling and dramatic and so was Debashish Barui's Terrorism is Not the Last Word.

What seemed to be significant though was that the artists negotiated a gamut of explorations on the psyche of fear. I cannot do justice to all the participating artists in this short space and will thus mention only a few as examples. One such work that stood out for its starkness was Fear by Dipyaman Kar. Another work that deserves mention for its appropriateness was the video-installation Nine to 99 by Chhatrapati Dutta. Sanhita Banerjee's tongue-in-cheek Vote Bank contrasted with the gravitas of Sanhita Ghosh's Looking Through Terror Chamber. Aditya Basak's video of candle flames and Manjari Chakraborty's Candles 1 & 2 were both silently poignant. In GR Iranna's work Morning Prayer Occupation one could almost hear the crunch of military boots, questioning the repressive power of the State. Debanjan Roy's untitled installation of a non-existent Gandhi under guard was eloquent as was Prabir Gupta's Testimony I Had to Feed My Family. Vivan Sundaram's involved installation Ways of Resisting and Binu Bhaskar's Mask were both chilling and dramatic and so was Debashish Barui's Terrorism is Not the Last Word.

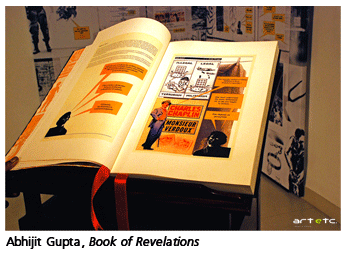

As for myself, I maintain that all killings whether committed by the state or non-state elements amounts to acts of terrorism. The pogroms against Jews by the Nazi forces, the Jalianwala Bagh massacre, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killings by the Khmer Rouge, as well as the nonchalance of the Western World towards 'collateral damages' in Iraq, Iran and elsewhere where unsuspecting civilians are killed is nothing less than terrorism. My installation/object Book of Revelations attempted to chronicle these acts of horror and genocide blurring distinctions designed to justify killings. “Wanton killing of innocent civilians is terrorism, not a war against terrorism,” says Noam Chomsky.

As for myself, I maintain that all killings whether committed by the state or non-state elements amounts to acts of terrorism. The pogroms against Jews by the Nazi forces, the Jalianwala Bagh massacre, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killings by the Khmer Rouge, as well as the nonchalance of the Western World towards 'collateral damages' in Iraq, Iran and elsewhere where unsuspecting civilians are killed is nothing less than terrorism. My installation/object Book of Revelations attempted to chronicle these acts of horror and genocide blurring distinctions designed to justify killings. “Wanton killing of innocent civilians is terrorism, not a war against terrorism,” says Noam Chomsky.

In conclusion, one can say that it was important to protest, by whatever means at one's disposal. Art Against Terrorism was a tool designed and deployed to register that protest. That is important, as Albert Einstein once said, “If I were to remain silent, I'd be guilty of complicity”.