- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

In the Summer of 1947

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Nanak Ganguly

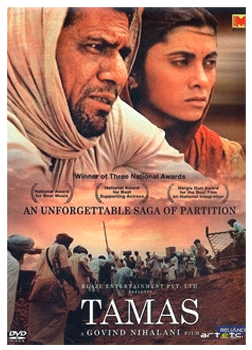

When Govind Nihalani approached Mandi House for clearance of tele- serial Tamas, the bureaucrats were stunned. It is the story of people trapped in Partition by Bhisham Sahni and that is a sensitive subject. But during its telecast the whole nation watched the serial for consecutive weeks with a stunned silence. The estimated number of viewer in the year 1988 was 3.5 crore. My essay is an attempt to explore and excavate that silence and as a practicing art critic, I would like to inform you the role of our modern artists during those cool days of “high” modernism and the stoicism we maintain even now when our people are drowned and killed in places like Kalimnagar, Singur and Uttaranchal. I will limit my discussion related to the artists till early Sixties when a different kind of “rupture” took place in our history and different set of artists emerged. While points of departure in the accounts of the Partition in literature or newspapers are varied, and in most cases preoccupied with causation, one may outline some major events which in turn were the culmination of certain processes earlier set into motion in the second half of the nineteenth century.

When Govind Nihalani approached Mandi House for clearance of tele- serial Tamas, the bureaucrats were stunned. It is the story of people trapped in Partition by Bhisham Sahni and that is a sensitive subject. But during its telecast the whole nation watched the serial for consecutive weeks with a stunned silence. The estimated number of viewer in the year 1988 was 3.5 crore. My essay is an attempt to explore and excavate that silence and as a practicing art critic, I would like to inform you the role of our modern artists during those cool days of “high” modernism and the stoicism we maintain even now when our people are drowned and killed in places like Kalimnagar, Singur and Uttaranchal. I will limit my discussion related to the artists till early Sixties when a different kind of “rupture” took place in our history and different set of artists emerged. While points of departure in the accounts of the Partition in literature or newspapers are varied, and in most cases preoccupied with causation, one may outline some major events which in turn were the culmination of certain processes earlier set into motion in the second half of the nineteenth century.

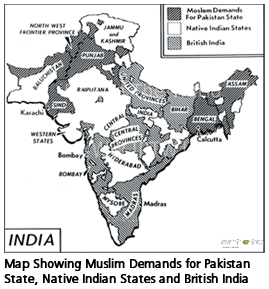

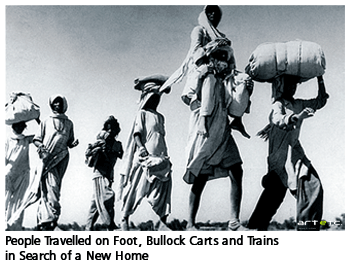

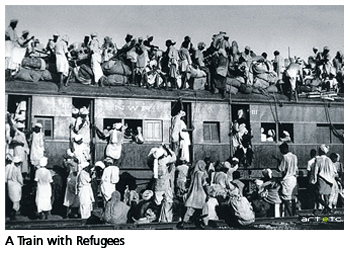

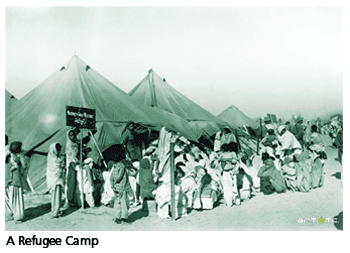

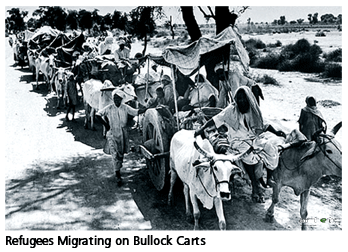

In the summer of 1947, the Partition of India was affected with catastrophic results. Ten million people were displaced and tenth of them were either slaughtered in the most singular civil war in recent history. There were no leaders, no armed forces, no plans, only a spontaneous and visceral ferocity whose legacy is more than evident even today. It has been a mere guess work that the victims dissolved into catatonic shock that displayed itself its silence. For a number of years after the event, no writer of any renown on either side of the national divide rescued an adequate sense of lucidity to approach the issue. Something has been permanently lost, and the inadequacy of mere words was discerned throughout the country in an understood code of silent mourning.

In the summer of 1947, the Partition of India was affected with catastrophic results. Ten million people were displaced and tenth of them were either slaughtered in the most singular civil war in recent history. There were no leaders, no armed forces, no plans, only a spontaneous and visceral ferocity whose legacy is more than evident even today. It has been a mere guess work that the victims dissolved into catatonic shock that displayed itself its silence. For a number of years after the event, no writer of any renown on either side of the national divide rescued an adequate sense of lucidity to approach the issue. Something has been permanently lost, and the inadequacy of mere words was discerned throughout the country in an understood code of silent mourning.

The following is a personal narrative (kindly remember such events experiences occurred with both the religious communities, it’s the same on either side of the divide): “While in the camp, my brother and I managed to visit our home with the help of a military guard. We saw our home partially burned, and saw a dead body probably of a child in the front room, but were unable to recognize the dead body of this child because it was badly decomposed. We then came back to our base camp with a terrible feeling of a deep personal loss.

We stayed in this camp for few days, and were transported later to another refugee camp in Lahore. From there, we crossed the Wagha border in a bus and arrived in Amritsar which was located in East Punjab, on the other side of the border, in the 'new' India. Later on, I learned through some published reports that Sikhs and Hindus of our town (Sheikhupura) were perhaps, after Rawalpindi and Multan, the worst sufferers at the hands of the Muslim fanaticism and cold-blooded murderous frenzy. The blow fell on us suddenly and swiftly, leaving between 10,000 and 20,000 dead in two days. The conspiracy that was hatched in Sheikhupura between the Muslim leaguers, the civil officers, Police and Military, for the extermination of Sikhs and Hindus of this town, and the district governed by it, is perhaps the worst on human record showing delivery on such a large scale.

Karamat Ali, a Minister in the West Punjab Government, and a resident of Seikhupura, played an active role in this conspiracy. All secret meetings were held with him to execute this plan. Nehru at the time, toured the West Punjab with Liaqat Ali Khan, estimated the number of those killed in Sheikhupura - the birthplace of Nanak - alone at 22,000.

On both the Pakistani and Indian sides, horrible atrocities were committed. Foot-weary convoys of refugees were attacked till the roads were clogged with corpses; trains were attacked and sent across the borders with bogies jammed with slaughtered passengers. No consideration was given to the sick or the aged or even to infants. Young women were abducted and raped.

On both the Pakistani and Indian sides, horrible atrocities were committed. Foot-weary convoys of refugees were attacked till the roads were clogged with corpses; trains were attacked and sent across the borders with bogies jammed with slaughtered passengers. No consideration was given to the sick or the aged or even to infants. Young women were abducted and raped.

Never in the history of the world was there a bigger exchange of population attended with so much bloodshed. It is estimated that over ten million people changed homes between East and West Punjab, and approximately 400,000 to 500,000 people were killed on both sides of the border. Nearly 150,000 to 250,000, mostly Sikhs, were killed in West Punjab alone. Those innocent people were murdered by Muslim goondas only because they were Sikh or Hindu.

I believe that we Sikhs suffered the most in terms of cost in human lives, property and wealth, and our rich Sikh heritage that was left behind in West Punjab during the Partition of Punjab and India in 1947, which we as a Sikh Nation should never forget, and must try to regain our glorious past with strong commitments and actions in order to build a strong future for our coming generations.

I believe that we Sikhs suffered the most in terms of cost in human lives, property and wealth, and our rich Sikh heritage that was left behind in West Punjab during the Partition of Punjab and India in 1947, which we as a Sikh Nation should never forget, and must try to regain our glorious past with strong commitments and actions in order to build a strong future for our coming generations.

We must also continue our fight for peace and justice so that all people can live with dignity and without fear.

When we were being transported in a bus from Sheikhupura refugee camp to Lahore, and then to Amritsar in India, I noticed the monsoon burst in its full fury; rivers rose; roads were submerged; bridges collapsed; train tracks were washed away. In refugee camps, cholera broke out. Corpses of dead animals and human beings were scattered on the road sides. The floods wiped the bloodstains off the land.

These are the awful scenes that are still fresh in my memory. Though a long time has elapsed since the Partition holocaust occurred, I nevertheless feel the same pain of loosing our loved ones as then. I sincerely pray that no one should ever go through this situation again. In any human tragedy of such a scale, the survivors, particularly the children, suffer the most when their parents, brothers and sisters are killed before their eyes by members of mad gangs for no reasons. I don't know how long such human tragedies will be going on before the world will wake up, and put a stop to this madness which is fanned by hatred and communal frenzy.”

(-from Partition & I: Oh! the Things We Do to Each Other' by Kuldip Singh Neelam, http://www.sikhphilosophy.net/1947-partition-of-india/28853-partition-blues-oh-things-we-do.html)

In the field of writing, the reason is more than obvious: any “non-factual” account of the event is apparently capable of re-exploding into another full scale civil war. Gyanendra Pandey writes, “… Histories of Partition, too, are generally written up as histories of “communalism”. They are not even, to any substantial degree, histories of confused struggle and violence, sacrifice and loss; of the tentative forging of new identities and loyalties; or of the rise among uprooted and embittered people of new resolutions and ambitions. Instead they tend to be accounts of the “origins” and “causes” of Partition… In spite of the emergence of two, now three, independent nation-states as a result of Partition, ‘India,’ this historiography would seem to say, stayed firmly –and “naturally” – on its secular, democratic, nonviolent and tolerant path… to build “the just and the good society” unaffected by the Partition. There is pain and sadness at what can only be read as the hijacking of an enormously power and noble struggle” (- In Defense of Fragment). This does not imply, however, that no writing was accomplished upon the Partition, on the contrary, the usual analysts of trauma- social scientists and the historians produce histories, biographies, autobiographies, statistical surveys, a positive sweep of ‘factual’ narratives usurped the stretch-in fact narrative history attempted to define what narrative fiction declined even to contemplate. The iconoclastic author of Urdu, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, who lived the ‘Age of Progressives’, a golden period of Urdu literature was among the Partition’s most violently distressed voices. Manto’s stories have, by and large been noticed against two contemporary backdrops: that of the Progressives, a cluster of ideologically motivated writers deeply responsive to European and Anglo-American intellectual trends, and that of “realism”, a propensity which has been commented upon repeatedly in any analysis of his tales that one is likely to come across. At times he has been hailed as a fellow Progressive, and at times denounced as destructively obsessed with carnality. The best that can be said about this equivocal affiliation is that there were periods of overlap between the aims of Progressives (a broadly left-of –centre writing, we also have a handful number in modern Indian Art) and the aims of Manto’s undefined and experimental oeuvre. But I do not talk here about Manto or Quarratulain Hyder or Rajinder Singh Bedi but about our crorepati auction artists. The best of literature that emerged in the wake of the partition or films by Ghatak or Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice Candy Man bear the imprint of the struggle to grapple with pain and suffering on a scale that was unprecedented in South Asia.

In the field of writing, the reason is more than obvious: any “non-factual” account of the event is apparently capable of re-exploding into another full scale civil war. Gyanendra Pandey writes, “… Histories of Partition, too, are generally written up as histories of “communalism”. They are not even, to any substantial degree, histories of confused struggle and violence, sacrifice and loss; of the tentative forging of new identities and loyalties; or of the rise among uprooted and embittered people of new resolutions and ambitions. Instead they tend to be accounts of the “origins” and “causes” of Partition… In spite of the emergence of two, now three, independent nation-states as a result of Partition, ‘India,’ this historiography would seem to say, stayed firmly –and “naturally” – on its secular, democratic, nonviolent and tolerant path… to build “the just and the good society” unaffected by the Partition. There is pain and sadness at what can only be read as the hijacking of an enormously power and noble struggle” (- In Defense of Fragment). This does not imply, however, that no writing was accomplished upon the Partition, on the contrary, the usual analysts of trauma- social scientists and the historians produce histories, biographies, autobiographies, statistical surveys, a positive sweep of ‘factual’ narratives usurped the stretch-in fact narrative history attempted to define what narrative fiction declined even to contemplate. The iconoclastic author of Urdu, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, who lived the ‘Age of Progressives’, a golden period of Urdu literature was among the Partition’s most violently distressed voices. Manto’s stories have, by and large been noticed against two contemporary backdrops: that of the Progressives, a cluster of ideologically motivated writers deeply responsive to European and Anglo-American intellectual trends, and that of “realism”, a propensity which has been commented upon repeatedly in any analysis of his tales that one is likely to come across. At times he has been hailed as a fellow Progressive, and at times denounced as destructively obsessed with carnality. The best that can be said about this equivocal affiliation is that there were periods of overlap between the aims of Progressives (a broadly left-of –centre writing, we also have a handful number in modern Indian Art) and the aims of Manto’s undefined and experimental oeuvre. But I do not talk here about Manto or Quarratulain Hyder or Rajinder Singh Bedi but about our crorepati auction artists. The best of literature that emerged in the wake of the partition or films by Ghatak or Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice Candy Man bear the imprint of the struggle to grapple with pain and suffering on a scale that was unprecedented in South Asia.

History, as Hayden White demonstrates, retains the rhetorical tropes of narrative fiction, creating a plot where the Antecedent (villain) generates the Consequence (victim), and it plays with variations of this plot, so that one may have a historical narrative dealing with several Antecedents, generating several Consequences and thus all history (moral in intent) plays out the chronicle in the rhetorical tones of an inevitable genre, for example tragedy, or melodrama, or farce. In fact History’s rhetorical tropes are inadequate to the substantiality of suffering, it deals with anguish by quantifying pain; statistics and numbering the dead appropriate the unique status of grief. Each historian focuses on one particular cause as being of prominent consequence which turns out to be either one of the following; political mismanagement (Wali Khan, Facts and Facts, The Untold Story of India’s Partition, 1987), the Muslim League’s inordinate demands (Braj Kishore Singh, The Indian National Congress and the Partition of India, 1990), unavoidable haste (Raza, Mountbatten and the Partition of India 1989), Gandhi (Sandhya Chandra, Gandhi and the Partition of India, 1984), Mountbatten (Sherwani,1986; Hamid, 1986), Hindu Nationalism (Stanley Wolpert, The Roots of Confrontation in South Asia, 1982), Jinnah (Manmath Nath Das, 1982; Spear 1961) and Nehru (Wolpert, 1982). Only two historians dare dodge the issue, the one by simply not speaking of it (Chandra,1988) as I mentioned earlier from a quote by Gyanendra Pandey , and the other by taking the cause-effect to its narrative limit by asking the question in the very title of his sensationalist booklet Was India’s Partition Avoidable? (Hiren Mukherjee, 1987; in other words, “Could the causes of the effect have been controlled”?). Interestingly, the answer is a qualified “Yes”. Then my question is why our modern art practitioners who are lauded and included in the Hall of Fame by the big auction houses for whooping crores of rupees remained insensitive unlike the writers of Hindi, Bengali or Urdu literature or couple of filmmakers. Why they rather looked up to European painters or Paris or New York and in the late Fifties to London especially in Baroda for their single unabashed source of inspiration. Had there be no one who witnessed or were caught in the midst of events and atrocities that marked the event at the border of two new countries and sense of displacement and performance that created a brutal realignment. I will explain that. There will be protests here citing Santiniketan or throwing up of names like Zainul Abedin or Somnath Hore but the question I want to raise in this paper still remains to be probed extensively.

The hyperreal Europe continued to dominate the Moderns, which is to be understood as a known history, language and imagery, which already happened elsewhere, and which is to be produced, mechanically or otherwise, with a local content. This only in turn becomes a task of reproducing what Meaghan Morris calls “the project of positive originality.” The modernists unselfconscious but nevertheless blatant example of “inequality of ignorance” in art practice finds resonance in the following sentence from a recent text by Salman Rushdie on postmodernism: “Though Saleem Sinai narrates in English…his intertexts for both writing history and writing fiction are doubled: they are, on the one hand, from Indian legends, films, and literature and, on the other, from the West- The Tin Drum, Tristan Shandy, One Hundred Years of Solitude, and so on.” This teases out not only those references that are from “the West.”...The author is under no obligation here to be able to name with any authority and specificity the “Indian allusion” that make Rushdies intertextuality “doubled.”(-Dipesh Chakraborty, Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History, A Subaltern Studies Reader, ed. Ranajit Guha). Aspired to look up to Europe, anxious they were, artists of a young nation state, they accepted the notion of modernism which came as a part of the colonialist’s baggage as the patriarchy of their creative thought process and end up mimicking later to be severely ripped apart by western art critics as a mere appendage of what was happening in the West. Nothing could be a better example of cultural mimesis than our project of Indian modernism ending in a poor variation of what could be called European modernism. Let us exactly explore that.

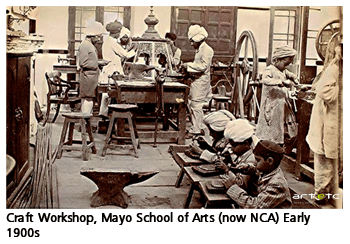

The modernist hegemony of culture was relatively unknown in India till the middle of last century. Heightened perceptions of the individual and his inherent right to freedom were inextricably linked to the cause of nationalism as the prospect of Independence came nearer. At the outset, the establishing of art schools was governed by the notion about what after all was to be promoted as art in the colonized country. The whole object of art schools was to encourage the craft tradition, in the process ensuring a steady supply of moderately priced utility objects. When art schools were established, 1853 in Madras, 1854 in Calcutta, 1857 in Bombay, the last one in 1872 in Lahore, an almost schizophrenic situation existed where the largely craft and industrial goods oriented students were on one hand encouraged to develop their own tradition which was non- realistic and decorative and on the other hand to perfect the imitation of reality outside. The first reaction to academic realism which was derived from the syllabi of Kensington School was provided by E. B. Havell when he joined the Calcutta School of Art in 1896. Havell located Indian art in a classical Hindu past which was systematically eroded by the “blight oh Mohammedan bigotry, political anarchy and British philistinism.” In his sharply polarized view of eastern versus western art, he was to present Abanindranath Tagore as the main progenitor of this truly Indian art. The school of painting which grew around Abanindranath and came to be called the Bengal school, placed emphasis on ideal or spiritual figures both ephemeral and timeless , emerging from a sheet of mist signifying ideals which in time came to equated with those of the nation. In their self-conscious Orientalism they borrowed from various schools of miniatures and introduced themes which could be applied to the present. Abanindranath used colour rather than line, and in course of time, the wash technique which he had learnt from Kakuzo Okakura, a Japanese artist, further enhanced their evanescent quality. One of his important paintings in the wash technique, Bharat Mata, made in 1904-05 is of a beautiful young ascetic holding in her multiple arms the blessings of food, clothing, learning and spiritual salvation, with a halo around her head and white lotuses at her feet. The painting is both mystic and transcendental, symbolizing the idea of a nation. If the neo-Bengal school’s main contribution lay in severing its bonds with academic realism and, by implication, with colonial domination over both art and imagination, by romanticizing and mythologizing its self-image, it had served the cause of Orientalism. Implicit also, was strong racial theory where the glorious Aryan past became the true representative of Indian civilization. Aryan India formed the cornerstone of a national image.

In reaction to this, plagued by a question of identity, two group of artists named ‘Calcutta Group’ and ‘Progressive Art Group’ came together in Calcutta and Bombay in 1943 and 1947 respectively to bring about an art which it allied itself with international trends more reflective of their own reality. The Calcutta group consists of Nirode Mazumdar, Paritosh Sen, Gopal Ghosh, Gobardhan Ash, and the Bombay group with spokesman Mulk Raj Anand consisted F.N. Souza, S. H. Raza and K.H. Ara and incorporated in the following years M.F. Husain, H.A Gade and Sadanand Bakre, Akbar Padamsee, Ram Kumar, Krishen Khanna, Bal Chabbda, Shiavax Chabbda and together they were to forge a brave new world. In their rejection of academic art, in their firm belief in the autonomy of the painterly image, in their undoubted use of methods employed by the school of painters and in their quest of self-expression, the Group was considered our first group of modernists. I understand cultural diffusion is a universal phenomenon and one which can be seen enriching but the more relevant question is how art is borrowed and value is invested with it. F.N. Souza and even Paritosh Sen were candid in expressing that and felt no misgivings. In an interview given to me for the Statesman, dated Feb 13, 1990, Paritosh Sen said, “As you know Picasso drew the human face. They were magnificent. These fellows gave up after Picasso and became abstract or they painted garbage cans, thereby avoiding the whole problem of finding a new draughtsmanship. I am the only artist to have taken a step further...” isn’t this evidence enough for mimesis.

“I think we should remember-History lies not by misrepresenting reality but exiling emotions”- this is Ashis Nandy’s reaction on our collective amnesia. Our moderns exactly did that. And exactly why, for the first time in my career, I write on our art history only showing a few works by Satish Gujral, because beside Gujral I could not find works by any other artist to go with the subject. Particularly in that period of reinvention since the culturally defining moments of the 60’s have come increasingly to embrace the dual realities of post-war, post-famine multi- cultural immigration and of their subcontinent context, resulting in a consequent revitalization of cultural priorities and objectives but that was a different expression, a different language and the time almost two decades later and a new generation of artists. Today they operate as paradoxical re-investiture in nomadic tradition, but transposed into the urban landscape. Integration in so much recent Indian art of landscape, myth and language with the ironic expressions of sub-cultural style is centrally characteristic of them: its meaning is explicit as within an interconnecting urban social attitude.