- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

Market Insight

The eastern art market recently received a celebrity patron. On March 6, at the VIP opening of AADAA’s The Art Show, British artist Damien Hirst picked up a drawing by Japanese painter and draughtsman Yoshimoto Nara. Nara, of course is blue-chip by Hirst’s standards, (before this, he had dropped $ 750,000 on a collection of photographs of shapely drieries by fashion photographer Raphael Mazzucco at an Art Basel Miami Beach event in December last year), and thus this move made headlines in the art circles immediately.

There is enough reason for this to be a big news in art circles, as this goes on to further establish how sought-after the far east art-market has become. This has mainly been due to China, championed mainly by the country’s increasing number of burgeoning rich, for whom, according to Meg Maggio, director of Pékin Fine Arts, a Beijing gallery specializing in contemporary art, “It's not enough to be wildly wealthy. For all these guys, it's about building a beautiful way of life—they want the nice objects, the good wine, the whole package.”

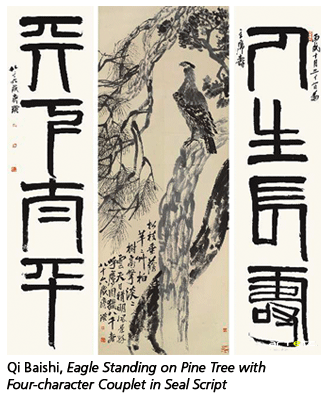

The Wall Street Journal’s Kelly Crow, in a ‘revealing’ study of how the upwardly mobile, ambitious, new Chinese collector functions, writes, “The art market is being transformed by Chinese collectors willing to pay top dollar for everything from Ming vases to contemporary Chinese abstracts. In some cases, these works are outstripping prices paid for blue-chip Western artists like René Magritte and Clyfford Still. “Three of the 10 most expensive art works sold at auction last year were by Chinese artists, according to art-market analyst Artprice. Last year's priciest painting: Eagle Standing on Pine Tree (1946) was by self-taught painter Qi Baishi. This delicate scroll rocketed ahead of colourful canvases by Pablo Picasso, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol when it sold for $65 million at auction house China Guardian in May. Overall, purchases by Chinese collectors accounted for roughly a fifth of Christie's global sales during the first half of last year; Sotheby's says mainland buyers also lifted its sales in Asia to nearly $960 million last year, up 47% from 2010.”

The Wall Street Journal’s Kelly Crow, in a ‘revealing’ study of how the upwardly mobile, ambitious, new Chinese collector functions, writes, “The art market is being transformed by Chinese collectors willing to pay top dollar for everything from Ming vases to contemporary Chinese abstracts. In some cases, these works are outstripping prices paid for blue-chip Western artists like René Magritte and Clyfford Still. “Three of the 10 most expensive art works sold at auction last year were by Chinese artists, according to art-market analyst Artprice. Last year's priciest painting: Eagle Standing on Pine Tree (1946) was by self-taught painter Qi Baishi. This delicate scroll rocketed ahead of colourful canvases by Pablo Picasso, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol when it sold for $65 million at auction house China Guardian in May. Overall, purchases by Chinese collectors accounted for roughly a fifth of Christie's global sales during the first half of last year; Sotheby's says mainland buyers also lifted its sales in Asia to nearly $960 million last year, up 47% from 2010.”

That Qi Baishi had skyrocketed past Picasso, even if it was in just an auction, had been noted and discussed by Art Etc news and views sometime back. However, it must be noted that Baishi, who is considered to be an important artist by collectors in his home country, is still to gain the status of a star in the West, and his success last year is noted by the Western media with surprise more than with pride and recognition. And that sentiment springs from the fact that Baishi’s astronomical price was achieved at China Guardian—one of the frontline Chinese auction houses in the mainland, in a country which, by government dictum still disallows western and/or global art auction houses to enter that geographical area.

And thus, while the world looks with wonder at the astonishing growth and enormous robustness of the Chinese art market, as well as Chinese artists, the global art media’s observations on the Chinese prospects are peppered with speculative scorn.

This comes through clearly in arguably one of the world’s best news agency’s report on the Chinese art market. Earlier this year, Reuters flashed a headline ‘Tread carefully in Chinese art market, experts say’. Interestingly, this came just after Artprice’s report on Qi Baishi’s sprint past Picasso on the auction floors.

Kevin Lim, in that report, wrote, “Investors should not indiscriminately buy pieces by popular contemporary Chinese artists since commercial success has made some complacent and later paintings and sculpture may lack the originality of earlier work, art advisers warn.

Asia's wealthy have showed increased interest in art in recent years, pushing up prices and sparking concerns of a bubble -- particularly in the market for contemporary Chinese art as the country rises as an economic and political power.

“In Hong Kong, auction market turnover skyrocketed 300 per cent from 2009 to 2010. Citigroup estimates that Chinese buyers accounted for 23 per cent of the $61 billion in global art sales last year.”

“Some collectors like to think values will continue to rise due to limited supply and continued strong demand as Asian collectors become more affluent, but not all pieces will necessarily do well, experts said.”

The Reuters report expanded on the argument, quoting Suzanne Gyorgy, a director at Citi Private Bank Art Advisory and Finance, who, “advises wealthy clients about their collections.” According to Gyorgy, they “can be buying the right name and the wrong pieces, and (their) collection is not going to increase in value.”

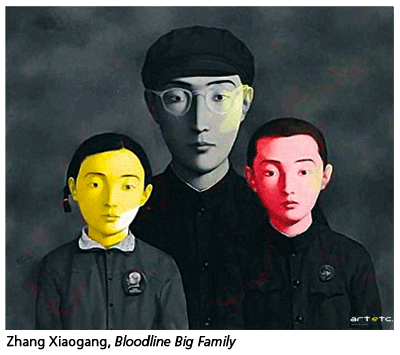

Elaborating on the point, the report gives the example of Chinese artist Zhang Xiogang. “Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series (a 1994 creation)– stylized portraits of imaginary Chinese families with piercing eyes –sold for $8.4 million last year (2011) at a Sotheby's auction in Hong Kong, but a 2005 piece by the same artist fetched just $1.2 million at a Christie's event.” And Gyorgy explained the cause—“The work they (the artists) are doing now is really just kind of miming the original work.” The report added that “Part of the reason is artist wariness about trying new things for fear their income may take a hit.”

Elaborating on the point, the report gives the example of Chinese artist Zhang Xiogang. “Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series (a 1994 creation)– stylized portraits of imaginary Chinese families with piercing eyes –sold for $8.4 million last year (2011) at a Sotheby's auction in Hong Kong, but a 2005 piece by the same artist fetched just $1.2 million at a Christie's event.” And Gyorgy explained the cause—“The work they (the artists) are doing now is really just kind of miming the original work.” The report added that “Part of the reason is artist wariness about trying new things for fear their income may take a hit.”

That comment is typical of how the West sees the East—a landmass inhabited by a people largely forced to years of subjugation and sapped of its ability to take decisions and risks.

Even in an apparently salutary piece in the World Street Journal, two days before the Reuters report, the scorn and suspicion was apparent. Profiling a Chinese collector, Yang Bin, by profession one of Sanghai-Beijing’s biggest car-dealer, and by passion an art collector, the writer Kelly Crow refrains from editorial comments but filters out such information from Mr. Yang’s art-auction sojourns, that leaves the impression of a typical Chinese collector, like Mr. Yang, who are among the main movers for the burgeoning art-trade in the country, as one who understands less and is more concerned about showing-off and spinning investment, somebody who may not as yet, but may well turn out to be, more than a speculative collector rather than a high-brow connoisseur.

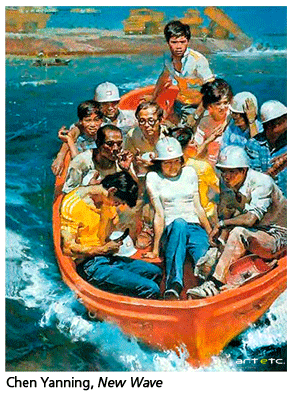

A part of the article goes like this: “Mr. Yang has also started offloading a few older pieces by Chinese realist artists like Chen Yanning as demand for their works has climbed. Last month (December 2011), Mr. Yang arrived at a Beijing luxury hotel and made his way into the packed salesroom of Poly, China's biggest auction house. He stood in the back, his usual spot. Halfway through the sale, he pointed to a large painting of a boatful of people hanging on the far wall. "That's mine," he said. He had paid roughly $60,000 for the 1984 work, New Wave, by Chen Yanning seven years earlier, and was ready to sell. Poly priced the work to sell for at least $629,000. When the bidding began, at least five collectors took the bait and the winner paid $1 million, a new price record for the artist.

A part of the article goes like this: “Mr. Yang has also started offloading a few older pieces by Chinese realist artists like Chen Yanning as demand for their works has climbed. Last month (December 2011), Mr. Yang arrived at a Beijing luxury hotel and made his way into the packed salesroom of Poly, China's biggest auction house. He stood in the back, his usual spot. Halfway through the sale, he pointed to a large painting of a boatful of people hanging on the far wall. "That's mine," he said. He had paid roughly $60,000 for the 1984 work, New Wave, by Chen Yanning seven years earlier, and was ready to sell. Poly priced the work to sell for at least $629,000. When the bidding began, at least five collectors took the bait and the winner paid $1 million, a new price record for the artist.

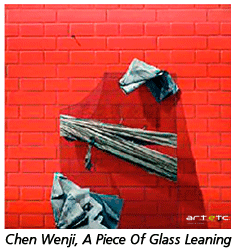

“At the same sale, Mr. Yang did some potentially strategic bidding of his own—on an artist represented by his wife's Aye Gallery. Mr. Yang enlisted a taller friend to stand in front of him and bid for one of Chen Wenji's photorealistic paintings from 1990, A Piece of Glass Leaning on Wall. Mr. Yang and his friend bowed out after other bidders pushed the price to more than double the work's $125,800 high estimate. It ultimately sold to a telephone bidder for $361,663, the artist's second-highest auction price. ’Two days later, What, a show of Mr. Chen's new works, opened at Aye. Mr. Yang says he bid on the work in part because early works by Mr. Chen are rare, and he doesn't own any, despite his wife's affiliation with the artist now. In addition, if he could help his wife's gallery by "keeping prices in a reasonable range, this would be good for the artist," he says.’

“At the same sale, Mr. Yang did some potentially strategic bidding of his own—on an artist represented by his wife's Aye Gallery. Mr. Yang enlisted a taller friend to stand in front of him and bid for one of Chen Wenji's photorealistic paintings from 1990, A Piece of Glass Leaning on Wall. Mr. Yang and his friend bowed out after other bidders pushed the price to more than double the work's $125,800 high estimate. It ultimately sold to a telephone bidder for $361,663, the artist's second-highest auction price. ’Two days later, What, a show of Mr. Chen's new works, opened at Aye. Mr. Yang says he bid on the work in part because early works by Mr. Chen are rare, and he doesn't own any, despite his wife's affiliation with the artist now. In addition, if he could help his wife's gallery by "keeping prices in a reasonable range, this would be good for the artist," he says.’

The fact remains that despite what numbers that statistical crunchers like Artprice may quote, Western auction houses are still too reluctant to stomach the growing potency of the Chinese art market and the enormous business that Chinese auction houses are generating, despite the handicap of a largely domestic market. That their entry is still barred from the mainland, and that they are forced to function out of Hong Kong thus losing out on the largest chunk of this potentially virile market of mainland Chinese collectors who are nagging the global auction houses no end and the Western media outfits are singing to their tune—as they have largely always done.