- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Dr. Nuzhat Kazmi

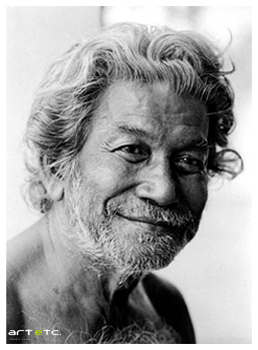

New Delhi. Ramkinkar Baij (1906-1980) was perhaps an artist who understood 'modernity' and its connections to art practice, undoubtedly more intuitively than in an informed or acquired manner, at least in his initial years, as a young artist in Santiniketan, Bengal. In actuality, contrary to more what is popularly understood, Ramkinkar was not a tribal. He was born in the Bankura district of Bengal and came from a lower middle class family. However, he had a natural flair to connect easily with the tribal lifestyle. He had a spontaneous empathy with all that was tribal, born as a result of close and constant association with the Santhal community living near Santiniketan. Ramkinkar lived nearly all his life in Santiniketan (he entered Santiniketan when he was just nineteen years old). A bond was established, sans any affectation or pretensions between the artist and his tribal subjects, visible to all giving rise to a much celebrated myth that Ramkinkar Baij was himself a tribal. A fable that was able to justify and explain his temperament and natural artistic disposition. Ramkinkar had an intellect; perhaps, much like what Gauguin went in search for in Tahiti, what he did not find while in France and he felt compelled to abandon the entire civilization of Europe for moments of naïve intelligence and beauty. Ramkinkar celebrated life itself in all his individualistic enterprises. He learnt with passion from all elements of life and existence that stirred him. He received an informed education that helped him to continue working on an eclectic approach to art, innate to his character. This was despite the fact that he had teachers who had clear views in regard to artistic practice as it was essential to develop in India of the 1930s. However, he was fortunate to have in them also mentors who realized his potential and his need to nurture individualistic artistic expression. He grew under the benign supervision of Rabindranath Tagore and Nandlal Bose, who were also grooming simultaneously, some of the most enterprising young talents in Santiniketan Kala Bhavan, including Binode Bihari Mukherjee. The progressive milieu of Santiniketan encouraged Ramkinkar to develop as an artist who was not only a sculptor but was a painter, printer, a theatre person and a singer as well. No boundary existed for him between any of these passions. He was able draw on these pursuits with creative force and strengthened his own individual artistic performance. He had a natural, holistic view of art and its practice. He remained committed to this view till the end of his life. His genius was uncluttered and unflustered. In Rabindranath Tagore's abode of peace Ramkinkar sustained his abilities to uphold a vision, a sense of discovery, and create an idiom that would express his natural impulses and transform an ordinary reality, person, object into a theme of celebration and thereby transforming it into an extraordinary and unique experience.

New Delhi. Ramkinkar Baij (1906-1980) was perhaps an artist who understood 'modernity' and its connections to art practice, undoubtedly more intuitively than in an informed or acquired manner, at least in his initial years, as a young artist in Santiniketan, Bengal. In actuality, contrary to more what is popularly understood, Ramkinkar was not a tribal. He was born in the Bankura district of Bengal and came from a lower middle class family. However, he had a natural flair to connect easily with the tribal lifestyle. He had a spontaneous empathy with all that was tribal, born as a result of close and constant association with the Santhal community living near Santiniketan. Ramkinkar lived nearly all his life in Santiniketan (he entered Santiniketan when he was just nineteen years old). A bond was established, sans any affectation or pretensions between the artist and his tribal subjects, visible to all giving rise to a much celebrated myth that Ramkinkar Baij was himself a tribal. A fable that was able to justify and explain his temperament and natural artistic disposition. Ramkinkar had an intellect; perhaps, much like what Gauguin went in search for in Tahiti, what he did not find while in France and he felt compelled to abandon the entire civilization of Europe for moments of naïve intelligence and beauty. Ramkinkar celebrated life itself in all his individualistic enterprises. He learnt with passion from all elements of life and existence that stirred him. He received an informed education that helped him to continue working on an eclectic approach to art, innate to his character. This was despite the fact that he had teachers who had clear views in regard to artistic practice as it was essential to develop in India of the 1930s. However, he was fortunate to have in them also mentors who realized his potential and his need to nurture individualistic artistic expression. He grew under the benign supervision of Rabindranath Tagore and Nandlal Bose, who were also grooming simultaneously, some of the most enterprising young talents in Santiniketan Kala Bhavan, including Binode Bihari Mukherjee. The progressive milieu of Santiniketan encouraged Ramkinkar to develop as an artist who was not only a sculptor but was a painter, printer, a theatre person and a singer as well. No boundary existed for him between any of these passions. He was able draw on these pursuits with creative force and strengthened his own individual artistic performance. He had a natural, holistic view of art and its practice. He remained committed to this view till the end of his life. His genius was uncluttered and unflustered. In Rabindranath Tagore's abode of peace Ramkinkar sustained his abilities to uphold a vision, a sense of discovery, and create an idiom that would express his natural impulses and transform an ordinary reality, person, object into a theme of celebration and thereby transforming it into an extraordinary and unique experience.

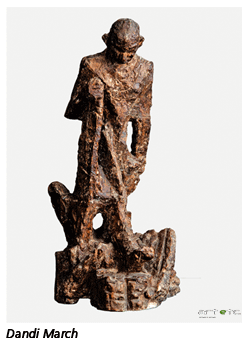

Perhaps one man who could inspire him and add wings to his liberated artistic ambitions was Gurudev himself. Rabindranath Tagore took upon himself to see that his young boy from a modest family background found his creative realization to the full capacity. He would converse with him, leave him with words of encouragement and ideas on which Ramkinkar would think and would internalize much what was suggested to him by the poet. He was once adviced by Rabindranath to work and fill Santiniketan with his art so as not to leave a single space untouched by his vision. Bharido was the vision he received and he strived to live up to it all his life. Ramkinkar, through his voice, his 'baulgaan', a tribal vision of a world of love and equality, as also his theatre, he indeed wrote his own plays and he extended his world view into his visual art. He explored all surfaces and techniques. His lifestyle rarely aligned with the 'bhadralok' sensibility, which it would not be incorrect to say, was then the ruling ethos at Santiniketan, as perhaps it still is. The art produced there was, in some ways, an expressed idiom through which this middle class awareness articulated itself most profoundly. It need to be observed here that Ramkinkar, was constructing his artistic affinities with clear political overtones when he made portraiture painting of freedom fighters, the themes of Non-Cooperation Movement against the British Rule in India. This was before he joined Santiniketan in mid 1920s, as a student of art. These overtly nationalist themes apparently were soon overtaken by a more idealistic and yet real humanity that he found in the world of the Santhal community. Undoubtedly Rabindranath's own world view helped the young artist to forsake early in his life a high pitched nationalistic overtones for a more real, as he envisioned, the future India and capture more exuberantly how India as a free nation could reinvent itself as a dynamic world culture.

Perhaps one man who could inspire him and add wings to his liberated artistic ambitions was Gurudev himself. Rabindranath Tagore took upon himself to see that his young boy from a modest family background found his creative realization to the full capacity. He would converse with him, leave him with words of encouragement and ideas on which Ramkinkar would think and would internalize much what was suggested to him by the poet. He was once adviced by Rabindranath to work and fill Santiniketan with his art so as not to leave a single space untouched by his vision. Bharido was the vision he received and he strived to live up to it all his life. Ramkinkar, through his voice, his 'baulgaan', a tribal vision of a world of love and equality, as also his theatre, he indeed wrote his own plays and he extended his world view into his visual art. He explored all surfaces and techniques. His lifestyle rarely aligned with the 'bhadralok' sensibility, which it would not be incorrect to say, was then the ruling ethos at Santiniketan, as perhaps it still is. The art produced there was, in some ways, an expressed idiom through which this middle class awareness articulated itself most profoundly. It need to be observed here that Ramkinkar, was constructing his artistic affinities with clear political overtones when he made portraiture painting of freedom fighters, the themes of Non-Cooperation Movement against the British Rule in India. This was before he joined Santiniketan in mid 1920s, as a student of art. These overtly nationalist themes apparently were soon overtaken by a more idealistic and yet real humanity that he found in the world of the Santhal community. Undoubtedly Rabindranath's own world view helped the young artist to forsake early in his life a high pitched nationalistic overtones for a more real, as he envisioned, the future India and capture more exuberantly how India as a free nation could reinvent itself as a dynamic world culture.

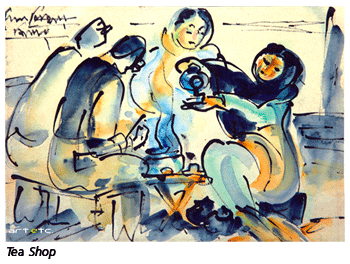

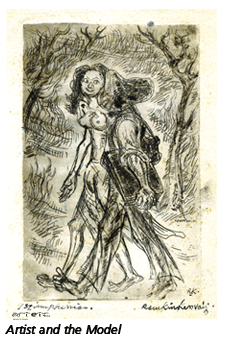

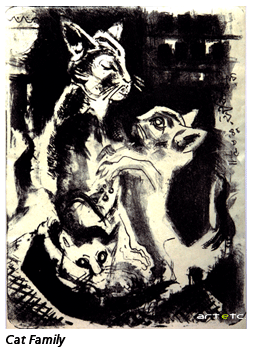

At another time Ramkinkar was suggested by Rabindranath Tagore, while he was working on a bust study of the poet, to enter the subject of his study as a tiger and with astute observation, as the tiger would suck his object's blood, to achieve what he wanted. And Ramkinkar is recorded to have said that after this episode he had never looked back. And indeed, when one looks at his body of work from small but intense works in etchings, to relatively large oils and watercolours of the artist we are compelled to notice their ferocious self absorption and utter intensity combined with an informed spontaneity. Ramkinkar made some brilliant studies of people all close to him in some context. A standing sculpture stands outside the Amar Kutir near Santiniketan, of Rabindranath by Ramkinkar. Another remarkable bust is in Budapest, Hungry, near Balaton lake, which captures the likeness of the poet, made just before he died in 1941. Another rare bust study is of Ustad Alauddin Khan who was in Santiniketan, and sat for his portrait by Ramkinkar. Ramkinkar, admirer of the Ustad for his music and his genius, had great love and understanding for music, music of all kind. He heard western music, introduced to it by his friends who included Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. He, of course was heard singing himself Lalongeeti of Lallan Faqir, in deep open voice as he also did render songs based on Rabindrasangeet.

When Ramkinkar died, on 23 March 1980, he had lived a full life, free but tempered by concerns both artistic and humanitarian. Radharani, his lifelong companion was beside him. He had not forgotten to see that she along with his nephew were his legal inheritors. While in hospital, frail and physically exhausted, the artist in him was active. A sculpted 'Durga' was left by him when his body was carried from the hospital and laid to rest in Santiniketan.

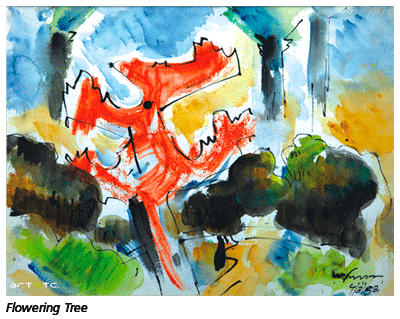

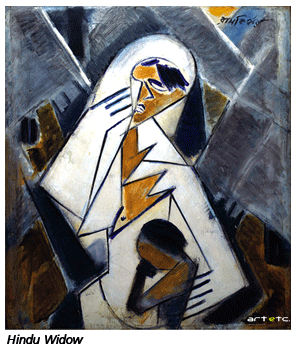

Ramkinkar Baij's treatment of form is inhibited and the contouring is sharp and in many sense expressionist. A person, who was involved in active theatre, writing his own plays and directing them, knew the dramatic content. This quality infiltrated into his plastic art with ease and an extraordinary flair. Apart from Rabindranath Tagore, who enhanced his artistic freedom, Ramkinkar had the opportunity to receive exposure to current western art practices through the visiting artists from Europe. Besides he was an artist who frequented the university library and could spent hours to find what he was looking for. Nandlal Bose proved to be a progressive teacher, in the sense, he did not hold Ramkinkar from going his way and in fact assisted him in cultivating his own visual language. Which, indeed was increasingly becoming expressionistic and fauvist, especially, in regard to his water colours. In his oil canvases his idiom could be said to be exploring a cubist sensibility without its structural integrity.

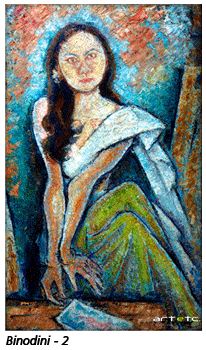

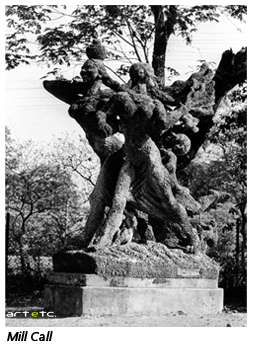

Some works that have come to be known more that others are his large monumental sculpture the Santhal family which can still be found installed in the campus of Santiniketan. His life studies and portraits of Binodini worked in all mediums of oil, watercolour, and bronze. However, there a numerous sculptures that can be a surprise delight all over the campus. One is the charming elephant playing with a young one sculpted in concrete. Another Santhal family group called 'Mill Call', now installed under a fiberglass canopy for protection from the elements of climate rain, hail and storm. Perhaps this is an attempt for preservation but definitely inadequate. It certainly needs more expert conservation here. The unfortunate fact is that Ramkinkar used material most easily available. Sometimes he could afford more but perhaps more because of an attitude that actually can be discerned. Therefore you are faced with the problem of preserving sculpture done in mud and clay, pebbles and cement contrite where material is bound to disintegrate in an open atmosphere. There is an interesting episode, which I think speaks for what the artist Ramkinkar, on occasion, thought of his own works and their future.

Some works that have come to be known more that others are his large monumental sculpture the Santhal family which can still be found installed in the campus of Santiniketan. His life studies and portraits of Binodini worked in all mediums of oil, watercolour, and bronze. However, there a numerous sculptures that can be a surprise delight all over the campus. One is the charming elephant playing with a young one sculpted in concrete. Another Santhal family group called 'Mill Call', now installed under a fiberglass canopy for protection from the elements of climate rain, hail and storm. Perhaps this is an attempt for preservation but definitely inadequate. It certainly needs more expert conservation here. The unfortunate fact is that Ramkinkar used material most easily available. Sometimes he could afford more but perhaps more because of an attitude that actually can be discerned. Therefore you are faced with the problem of preserving sculpture done in mud and clay, pebbles and cement contrite where material is bound to disintegrate in an open atmosphere. There is an interesting episode, which I think speaks for what the artist Ramkinkar, on occasion, thought of his own works and their future.

In 1975, that is well fifty years of Ramkinkar's professional art practice Ghatak commenced shooting on him in Santiniketan. The filmmaker sees him as a political icon too. Ramkinkar was an artist with leftist linings and aspirations. He is seen articulating the problems that he faces as an artist. He is filmed drawing with graphic details as to how he has saved himself from dripping roof by covering the holes in the roof with his oil paintings. When asked by Ghatak what he is going to do for the art exhibition that is coming soon. Ramkinkar has this answer, ”As the paintings are made by oil on canvas water will not do any damage to them. I can pull them out for the show. But my worry is what I will replace them with to stop the rainwater. It costs hundred rupees to buy grass for thatching. It is very expensive!” And thus he laughs off a serious situation of both art and living.

The sculpted Yaksha and Yakshini at the Revenue Bank of India's entrance in New Delhi, mark not only a free India's commissioned art projects but also the peculiar situation that underlined the questions of 'modernity' and of 'Governmental patronage'. These sculpture were ideas that grew from the need felt by Jawaharlal Nehru to embellish State building spaces with visual icons that lent themselves to Modern Indian ethos. Out of the nine artists invited to submit their proposals, only one submitted models and sketches. The proposal of Ramkinkar was accepted. The art form of the male 'Yaksha' was drawn from the 'Parkham Yaksha' in the Mathura Museum. The art form of the female Yakshini was inspired by the 'Bisnagar Yakshini', Calcutta Museum. Karl Khandalavala, art historian and lawyer, felt that these massive figures would go well with the architectural features. The themes of peasant-worker prosperity inspired by Nehru's 'scientific temper', was thus found. Its manifestation in the form of the Yaksha and Yakshini, at the same time, appealed to the sensibilities of those who valued tradition, which of course is different to different people. Yakshas belongs to a class of demi-gods and they are represented as in service of 'Kubera' the God of Wealth. The duty of Yakshas is to guard over Kuber's gardens and treasures. The Yakshini is a female counterpart of Yaksha. The Revenue Bank has the sole right to note issue and as a banker to the Central and State Government could, therefore, be compared with Kubera - the lord of wealth and thus the Yaksha and Yakshini could assume the duty of guarding the Bank's treasure. In the modern context, the figures could assume allegorical interpretations. They become here symbols of industry and agriculture, vital matter of concern to Revenue Bank of India.

Ramkinkar, took his own time in selecting the exact quality of stone that was needed. Exploration of sites, stone quality, problems in its quarrying and transportation to New Delhi, delayed the actual commencement of the project. While everyone had no doubt of Ramkinkar's artistic commitment they did have concerns over his managerial skills to undertake the enterprise. However, in January 1967 the sculptures finished and installed the original expense estimates had to be considerably revised. Finally installed, it was over ten years since they had been commissioned. The general political the outlook of the country as indeed of its leaders had changed considerably. The sculptures at the Reserve Bank's New Delhi Office at Parliament Street scandalised prudish sensibilities of the Delhi gentry who found it difficult to justify Yakshini nude presence in public domain. And the matter did not rest till it was raised in the Rajya Sabha.1 Blitz gave an interesting twist to the symbolism contained in the Sculptures. This time the highlight was on Yaksha when it carried the title Yaksha Patil, a photograph of the sculpture was carried and a comment “….But artist Ramkinkar's conception of a modern Yaksha, which now guards the Reserve Bank, has, coincidentally enough, taken an amazing likeness to Sadoba Patil, one of the most zealous 'guardians' of wealth and big business in the country…”

Ramkinkar, took his own time in selecting the exact quality of stone that was needed. Exploration of sites, stone quality, problems in its quarrying and transportation to New Delhi, delayed the actual commencement of the project. While everyone had no doubt of Ramkinkar's artistic commitment they did have concerns over his managerial skills to undertake the enterprise. However, in January 1967 the sculptures finished and installed the original expense estimates had to be considerably revised. Finally installed, it was over ten years since they had been commissioned. The general political the outlook of the country as indeed of its leaders had changed considerably. The sculptures at the Reserve Bank's New Delhi Office at Parliament Street scandalised prudish sensibilities of the Delhi gentry who found it difficult to justify Yakshini nude presence in public domain. And the matter did not rest till it was raised in the Rajya Sabha.1 Blitz gave an interesting twist to the symbolism contained in the Sculptures. This time the highlight was on Yaksha when it carried the title Yaksha Patil, a photograph of the sculpture was carried and a comment “….But artist Ramkinkar's conception of a modern Yaksha, which now guards the Reserve Bank, has, coincidentally enough, taken an amazing likeness to Sadoba Patil, one of the most zealous 'guardians' of wealth and big business in the country…”

This was Blitz's uncanny reference to Ramkinkar's Yaksha as Sadoba Patil, a well known face in Indian social circle and a contemporary industrialist.

Ramkinkar taught for many years and gave the Sculpture Department in Kala Bhavan a unique working temper. Ramkinkar came to know two sculptors Lisa Vonpott and Margaret Milward, artists of European origin. His fascination for human form widened into rethinking form itself and Western traditions were also accommodated by Ramkinkar with an empathy and interest in modernist exploration for new idiom and visual vocabulary. However, expressionism apparently was the idiom that articulated much of his mature artistic work. Ramkinkar sensitivity to the life of the dispossessed and the disadvantaged section of society was made more sharp and deep with his inclination towards socialist political thinking and his close association with intellectuals of the Left thinking. He succeeded in translating it with intensity in his art. In a way Ramkinkar works reflect the ideological Left and his attempt to bring contemporary art and culture into active people's politics. An ideological energy was increasingly becoming visible in all spheres of national life, in the growing middle class and its vision of the political future. Perhaps one more extension of his artistic beliefs was that Ramkinkar did not make art with the intention to preserve them or commercially gain from his works. He created for expression and articulation of an idea. He used clay, cement or what he could afford. It was never easy to generate expensive material like metal and marble stone. What indeed was more important was for him was to work and create and work as an artist for the society.

Ramkinkar taught for many years and gave the Sculpture Department in Kala Bhavan a unique working temper. Ramkinkar came to know two sculptors Lisa Vonpott and Margaret Milward, artists of European origin. His fascination for human form widened into rethinking form itself and Western traditions were also accommodated by Ramkinkar with an empathy and interest in modernist exploration for new idiom and visual vocabulary. However, expressionism apparently was the idiom that articulated much of his mature artistic work. Ramkinkar sensitivity to the life of the dispossessed and the disadvantaged section of society was made more sharp and deep with his inclination towards socialist political thinking and his close association with intellectuals of the Left thinking. He succeeded in translating it with intensity in his art. In a way Ramkinkar works reflect the ideological Left and his attempt to bring contemporary art and culture into active people's politics. An ideological energy was increasingly becoming visible in all spheres of national life, in the growing middle class and its vision of the political future. Perhaps one more extension of his artistic beliefs was that Ramkinkar did not make art with the intention to preserve them or commercially gain from his works. He created for expression and articulation of an idea. He used clay, cement or what he could afford. It was never easy to generate expensive material like metal and marble stone. What indeed was more important was for him was to work and create and work as an artist for the society.

A visit to the ongoing retrospective exhibition at NGMA of Ramkinkar Baij, offers some brilliant insights to his creative virtuosity and intellectual commitments. There are works, and more especially some smaller ones like The Colt, etching, now in private collection. To say that he was the pioneer of modernist art in India will not be complete truth. For the modernity is discernible in India in artists' like Rabindranath Tagore, Gaganendranath Tagore and Jamini Roy and more can be added here. However, it would certainly be truthful to say that he was indeed a modernist, one of the few who make the earliest phase in India, who celebrated it with utmost abandonment and zeal. He has left behind him a great body of work that the Modern state of India has yet to learn how to conserve and preserve. Not wanting to end on a resigned note I would like to make an appeal to all concerned bodies, of government or non-government, to act fast, coordinate systematically and bring Ramkinkar Baij's contemporary modern legacy into a definite state of permanent existence accessible to all for all time. May his art remain a defining icon of Indian stepping into the phase defined as Modern.

Reference

1.Prof. Satyavrata Siddhantalankar: ‘Will the Minster of Works and Housing and Supply be Pleased to State:

•Is it a fact that the statue of a naked woman has been erected in front of the Reserve Bank of India, Parliament Street and

•If so what is the object in erecting this statue of a naked woman?’

An explanation that the ‘naked woman’ was essentially an allegorical interpretation, representing agriculture and wealth was perhaps somewhat convincing though not without further supplementary questions. His time in regard to the costs incurred and the details of the committee who recommended the art work.