- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Outlining the Language of Dissent

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

Golub, Botero and Spero reconciling the “dichotomy between quality and critique”

by Koeli Mukherjee Ghose

In the present time while discussing the part, politics plays as an ingredient in art, there exists a disagreement between the believer in its virtuosity and those who advocate the need for critical analysis. Amongst the supporters of virtue are Robert Hughes and Wilton Kramer, they criticize the disparagement of aesthetics that turn into a memorandum.

In a popular book published in 1993, Hughes criticized the employment of protest as a process in art making, by which he sharply pointed at the artists’ political views and an obvious inclination to imagine himself in a shroud of “victimhood “and interpret the world through his or her personal disappointments.

Hughes perhaps was referring to the notion of identity, as contemporary art theory recognizes issues related to minorities, women, and gay artists.

Around the same time Kramer opined for the return to principles of merit in art, declaring most of the goings on in the previous decades as the “revenge of the Philistines”. Kramer, took to the route of Clement Greenberg, the mid- century critic in his strong criticism of imposing peripheral distress such as politics, narratives, and biography into the making and estimation of art. Kramer and Hughes align with Greenberg in their critical positioning in holding on to the vision of pure art - significant in its triumph over all mandates.

While theorists and cultural critique – Hal Foster and Benjamin Buchloh, who supported an anti aesthetic positioning – criticized the creative mode of appreciation of beauty and pleasurable making of art as the core criteria and defining feature of the work, as held by Kramer and Hughes. Buchloh, Foster and those critics who were on the same path, considered the approach of appreciation of beauty and pleasurable making of art exemplified a “moral rot.” They thought it was necessary to oppose the route that dealt primarily with an idea, its effect, conveyance of a feeling emerging from it and the importance of its appearance were interpreted as - “false seductions of artistic representation.”

As opposed to the foundation of the conventional art appreciation that was distinguished by a conviction; in the artist’s freshness of imagination, the prospect of true self– expression, the belief that art is about applying and exerting one’s unique ability- Buchloh and Foster through their critical analysis presented that taking delight in aesthetics is an act of compliance to authoritarian political, economic and social mechanisms.

As a result although Hughes and Kramer were inclined towards aesthetic practice and notions of beauty, the critics, on the other hand supported the strong reactions of the artists towards commoditization of art as expressed by them in employing images from the media to expose their invasive action, underlining their resistance to comply in systems of political and psychic subjugation.

Eleanor Heartney in her essay Art & Politics states – “Between these black and white views, lie a gray area in which the dichotomy between quality and critique is far less absolute. Here artists adopt a variety of strategies to address the complexities of the political world borrowing from the classical art of rhetoric, they explore modes of persuasion that engage the audience’s emotions and intellect. They may exploit visual languages drawn from art history mass media and popular culture and new technologies that are opening up unprecedented channels of communications. For some it is enough to bear witnesses to the injustices and horrors of our times, while others take an activist stance encouraging viewers to become participants in political and social actions. Politically oriented artists also engage various kinds of audiences, from the art savvy to the general public. Within these approaches concern for aesthetics and critique is often equal, suggesting that beauty may in fact be a powerful tool in the rhetoricians’ arsenal.”

One of the most prominent “political artist - Leon Golub,” from the second half of the twentieth century, (1922- 2005), declined to discard figuration and realism. He surely contemplated upon the issue of aesthetic as he centered his vision in the art historical knowledge, absorbing stimulations from contemporary Greek sculptural reliefs, Abstract expressionism, and classical Roman wall paintings.

A writing by Anne Lafond and Sandy English reporting the retrospective of the artist’s work from 1950-2000, at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and While the Crime is Blazing: Paintings and Drawings of Leon Golub, 1994-1999 at the Cooper Union School of Art, closed September 11, 2001, states – “These expressive political paintings, many of which are mural-sized, explore issues of race, violence, war and human suffering. Viewers had an additional opportunity to view examples of Golub’s recent work, including Dionysiac (1998), Prometheus (1997), Breach (1995) and Like Yeah (1994) at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. These two shows offer an opportunity to assess the work of an artist who took on the task of painting the history of the past half-century.

As a young painter after the Second World War, first in New York and then in Paris, Golub did not go the route of abstraction, although his early work shared some of the techniques and formal concerns of the Abstract Expressionists. Like Pollock, he took to pouring paint onto unstretched canvas on the ground, and then scraped it to achieve a distressed surface that mimics the appearance of ancient sculpture: broken, fragmented, pock-marked, eroded. He depicted images of colossal nude men engaged in inexplicable, timeless, ritualized struggle. These monumental figures continuously emerge from and dissolve into the surface of the paint, and bespeak a spirit of human resistance in the face of overwhelming natural forces.

Golub was interested in the eternal, the quintessentially human. Hence also his frequent depiction of the sphinx, since it poses the questions: what is it to be man, what is it to be beast?

In the 1950s and ’60s Golub sought to grapple with the experiences of the Holocaust, Hiroshima and the subsequent wars in Korea and Vietnam in his Gigantomachies series. (A gigantomachy is a depiction of the ancient Greek mythical war between gods and giants for rule of the universe.) These five frieze-like paintings (from 2.7 x 5.5 meters to 3 x 7.5 meters) recall the Great Altar of Zeus from the Hellenistic city of Pergamon as well as such Renaissance reworking of the theme as Raphael’s Combat of Naked Men. Unlike his sources, Golub’s figures in these works are brutish, static and ugly. He seeks, unsuccessfully for the most part, to convey motion through blurring the figures into indistinguishable masses of spotty skin tones.”

Lafond and English mention that in the 1970s Golub decided- “to clothe his naked warriors in American Army uniforms, hand them machine guns and have them shoot across empty or cut-out canvas at huddled, screaming Vietnamese civilians. This was an important statement in a period when most of the art world averted its gaze from the American-perpetuated atrocity. Golub seems to be protesting a hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil art, like minimalism or Pop Art and its glorification of the cheap and mundane. The idea that what was really going on, in an aesthetic as well as political way, was the brutal conflict in Vietnam was certainly a welcome contribution to the artistic depiction of reality.”

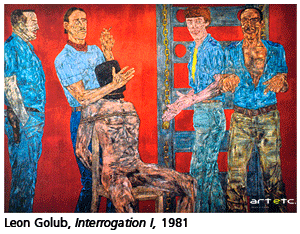

Golub’s repugnance of the Vietnam war made him consciously move away from his classical inspirations visible in his earlier paintings depicting masculine strength, towards topical imagery to emphasize the factual and emotional gap “between a cluster of armed combat ready - US soldiers and a group of frightened Vietnamese villagers” - as described by Heartney. Evolving consequentially from his imagery, Golub approached his Mercenaries and Interrogations series in the 1980’s, news reports and documentary photographs of the brutality of right wing death squads in Latin America, were his material of factual reference for these works. In this series Golub investigates the gloomy facet of the human determination for possessing power and control. Golub would habitually graze his canvases with a meat hatchet to create a visual effect of brutality. Golub’s paintings link the propinquity of the newspaper reports in his imagery with a strong implication of primeval and a sense of timeless adversity.

Golub’s repugnance of the Vietnam war made him consciously move away from his classical inspirations visible in his earlier paintings depicting masculine strength, towards topical imagery to emphasize the factual and emotional gap “between a cluster of armed combat ready - US soldiers and a group of frightened Vietnamese villagers” - as described by Heartney. Evolving consequentially from his imagery, Golub approached his Mercenaries and Interrogations series in the 1980’s, news reports and documentary photographs of the brutality of right wing death squads in Latin America, were his material of factual reference for these works. In this series Golub investigates the gloomy facet of the human determination for possessing power and control. Golub would habitually graze his canvases with a meat hatchet to create a visual effect of brutality. Golub’s paintings link the propinquity of the newspaper reports in his imagery with a strong implication of primeval and a sense of timeless adversity.

A similar act of resolving come into view in the Abu Ghraib paintings by Fernando Botero a Columbian artist (born -1932). Botero is popular for his mannerist style (known as Boteroism), depicting rotund figures and nudes. Eleanor Heartney mentions –“In 2004 he took on a much darker subject in a series of paintings based on published accounts of torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. While they present details familiar from news reports – the bras and panties the prisoners were forced to don, the snarling dogs the combat boots and latex gloves worn by the guards – these paintings also contain deliberate echoes of traditional Christian iconography.” Hooded figures tied and bound take on postures reminiscent of medieval and renaissance paintings - and the pain and anguish of Christ and the saints. They also bring to mind Golub’s series titled Mercenaries, but while Golub accentuated the perverse thoughts of the tormenters, Botero’s concentration lay in the captives and the bruise and wounds their bodies bore, suggestive of their experience of torture. The prison dogs are evocative of the phrase ‘hounds of hell’ - an intensely shocking image from the series, describes a dog attacking a prisoner who is lying on the floor face down and the back of his white T- shirt .

A similar act of resolving come into view in the Abu Ghraib paintings by Fernando Botero a Columbian artist (born -1932). Botero is popular for his mannerist style (known as Boteroism), depicting rotund figures and nudes. Eleanor Heartney mentions –“In 2004 he took on a much darker subject in a series of paintings based on published accounts of torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. While they present details familiar from news reports – the bras and panties the prisoners were forced to don, the snarling dogs the combat boots and latex gloves worn by the guards – these paintings also contain deliberate echoes of traditional Christian iconography.” Hooded figures tied and bound take on postures reminiscent of medieval and renaissance paintings - and the pain and anguish of Christ and the saints. They also bring to mind Golub’s series titled Mercenaries, but while Golub accentuated the perverse thoughts of the tormenters, Botero’s concentration lay in the captives and the bruise and wounds their bodies bore, suggestive of their experience of torture. The prison dogs are evocative of the phrase ‘hounds of hell’ - an intensely shocking image from the series, describes a dog attacking a prisoner who is lying on the floor face down and the back of his white T- shirt .

Lucinda Barnes, chief curator and director of programs and collections in her note mentions “Internationally acclaimed artist Fernando Botero (b. 1932) offers a powerful vision of the atrocities of Abu Ghraib in a series of fifty-six paintings and drawings, which has now returned to Berkeley as an extraordinary gift from the artist to the permanent collection of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Thousands of Bay Area visitors first saw this group of works in early 2007, in an exhibition at UC Berkeley’s Doe Library organized by the Center for Latin American Studies, one of the first presentations of the series in North America. The Colombian-born artist has made this magnanimous gift in response to the enthusiastic interest in the series from the Berkeley community and in recognition of Berkeley’s historic role in the arena of free speech. In May 2004, The New Yorker published one of the first accounts of abuses at Abu Ghraib, written by Seymour Hersh, a Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative journalist who first came to renown for exposing the My Lai Massacre in 1969. Hersh’s article, Torture at Abu Ghraib,was a horrific account, drawing heavily upon a fifty-three-page report by Major General Antonio M. Taguba detailing what the general described as “sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses” at the prison.

Hersh enumerated many of the sickening abuses and humiliations detailed in the Taguba report, and also described the now famous photographs that had been released just the week before on 60 Minutes II. Fernando Botero read Hersh’s article while on a flight to Paris, where he lives and works. Even before the plane landed, Botero began sketching the horrific scenes that he imagined based on what Hersh had written. Back in his studio, Botero continued drawing and painting in an intense torrent of work that continued for fourteen months. Botero numbered the works in sequence as he made them, Abu Ghraib – 1 and so on, as if creating a chronicle of his own response.

In an interview with UC Berkeley professor and former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass, Botero remarked, “What I wanted was to visualize the atmosphere described in the articles, to make visible what was invisible.” During his 2007 visit to the Berkeley campus, Botero told San Francisco Chronicle critic Kenneth Baker that his Abu Ghraib paintings were works “of imagination and not documentary.” Fernando Botero’s early interest in art was sparked by an exhibition of works by the famed Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros; noting that “they made the reality of the country the subject of their art,” Botero saw in their paintings a “direct way of speaking.” As a young artist, Botero traveled to Europe to study the masters in Spain and Italy. Based in New York in the 1960s, later settling in Paris, Botero became known for lively compositions of volumetric, sensual figures. Yet his works also have often criticized military juntas and dictators as part of Latin American history and culture, as well as the violence and drug wars in Colombia. These works clearly show the influence of the Spanish master Francisco Goya, who mocked the royals and the Church of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Spain, and whose famous series Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) responded with outrage to the brutality of the Napoleonic invasions, through which the artist himself lived.”

Although the paintings bear allusion to specific events, these works surpass the limitation of the specific. The image is Poignant with a universal premise as the unjustified brutality of subjugators towards the incarcerated and the ability of one individual to take away all what's left of sense, safety and pride from another being gets highlighted.

Nancy Spero, born in1926 in Ohio, is inspired by ‘traditional imagery’, and like those of Golub and Botero, her paintings are flooded with a sense of fury and grief. To the natural, volatile liveliness that differentiate the works of Golub and Botero, Spero’s paintings are distinctly subtle and radical, like Chinese scrolls her images bear marks of being stenciled, stamped, collaged or traced onto see-through papers that open up from corner to corner on the wall. Laura Cumming, the art critic of The Observer since 1999, elucidates “It is a truth rarely in need of mention that an artist's reputation may depend on more than art. The life, the deeds, the opinions, the death, all may have their influence on posterity. But when the American artist Nancy died in 2009, at 83, the US press explicitly emphasized her anti-war activism and her campaigns to raise the status of women artists in a male art world as if they were inseparable from her work, which may well be true. Spero herself, it is said, drew no distinction.

Nancy Spero, born in1926 in Ohio, is inspired by ‘traditional imagery’, and like those of Golub and Botero, her paintings are flooded with a sense of fury and grief. To the natural, volatile liveliness that differentiate the works of Golub and Botero, Spero’s paintings are distinctly subtle and radical, like Chinese scrolls her images bear marks of being stenciled, stamped, collaged or traced onto see-through papers that open up from corner to corner on the wall. Laura Cumming, the art critic of The Observer since 1999, elucidates “It is a truth rarely in need of mention that an artist's reputation may depend on more than art. The life, the deeds, the opinions, the death, all may have their influence on posterity. But when the American artist Nancy died in 2009, at 83, the US press explicitly emphasized her anti-war activism and her campaigns to raise the status of women artists in a male art world as if they were inseparable from her work, which may well be true. Spero herself, it is said, drew no distinction.

This is a thought worth holding in mind at the Serpentine Gallery, where 60 works on paper (with one exception) from 1956 to 2002 are currently on display. For it seems to me that much of what one encounters in this dark and tumultuous art gathers power and meaning precisely in terms of her political life. I don't say that they can only be understood this way; far from it. But context occasionally makes the latent strengths more apparent.

To describe them simply as works on paper, for instance, is to ignore a central point. For Spero made no other kind of work. She did not paint with oil on canvas – the canonical male medium – and she did not sculpt. She made her mark on paper with pen and pencil, ink and gouache, stencil and collage, and while one might argue that many men have done so too, Spero's renunciation was explicit. Such was the culture of second-wave feminism, with its subversion of archetypes and its repudiation of patriarchal traditions, including the predominant form of easel painting.

The cast of recurrent figures in Spero's prints and friezes is so common now, what is more, that it is worth remembering that it once shocked and embarrassed. Lilith, Medusa, the siren, the harpy, the Irish Sheela-Na-Gig - that Celtic fertility symbol gleefully exposing her open vulva, all of them redeemed: these figures were torn from time, from ancient art and folklore, from magazine and myth, and brought together in frenzied, all-together-now choruses.

…Azur, was made in 2002, but this was a Spero format for decades and it is easy to see that such stubborn art was not made to hang comfortably on the walls of upscale Manhattan galleries in the 1960s and 70s. Nor is hard to understand why the art world also bypassed the black paintings of that era.

Figures crawl through sepulchral gloom, angels appear out of seething darkness shrieking profanities, birth is violent, motherhood represented by a five-breasted monster. The paint is laid on like some weak pastiche of abstract expressionism, washy but intensely dark: passive-aggressive as Louise Bourgeois in the same period.

…And here is a curious dichotomy: between Spero's free inner visions and her more public-minded statements. For a good deal of her work is close to didactic. Take a piece like Body Count (1974), in which the words of the title appear over and again stencilled vertically on a long scroll, with a background of cross-hairs, so that one may count upwards or downwards, as it were, while the shooting goes on. Or The Eleventh Hour, also invoking Vietnam, which comprises 11 panels printed with the mounting numbers and scatter-bomb messages – Torture in Asia, Made in USA – each of them ringingly clear.

…War, torture, violence against women: these word-works are clearly a form of political expression, no matter that they offer no opinions and propose no solutions. For Spero's admirers, it seems they even constituted a kind of activism in themselves. "You could get killed making things like that," exclaimed the artist Kiki Smith on seeing her first Spero. To modern eyes, this consciousness-raising from inside the art scene looks far less potent than Spero's political protests in the real world beyond. But maybe you had to be there.

Where she really finds form is in the imagination, in the delicate but horrifying figments drawn in gouache so diluted it lies pale on the page. She produced these year after year, all through the Vietnam War, her rage and despair undiminished.

…A lexicon of disembodied faces emerges, each different, but all part of some timeless inferno that culminates in one of Spero's final works. A maypole of heads attached to ribbons and chains, goggling, spitting, leering, raging, crying, but all in two fragile dimensions, cut from sheets of aluminium, this is not quite sculpture and not quite drawing. Grim yet lightsome, it is a spectacle of hell tinged with the carnivalesque.

What strikes is that these victims may have been perpetrators themselves. Spero's vision is not one-sided. Bombs may be female, as well as male, likewise helicopters and war planes, letting down an undercarriage of breasts. These images are unforgettable and they are made to be so. They represent Spero at her strongest: a conscience making art to an unerring purpose, lest we ever forget the horrors of war.”

The massive, three tiered collage that goes around the wall and covers the four walls of the gallery, titled Azur, shows characters such as dancers, acrobats, Victims, avengers, warriors and drivers - all of whom are women . Spero’s compositions are defined by the condition of loss of memory –as similar images repeat, multiply, amalgamate and fade away through an ever changing backdrop. Spero draws images from archaeology, mass media, history and fantasy, her work investigate the prime example of female power and vulnerability. One painting can have images as varied as the screaming head of Marianne, symbol of the French revolution a alarming snake peaked Medusa; fertility figures; the German Valkyries, Greek Maenads, and the curved body of Nut the Egyptian sky goddess. Describing contemporary women - as an insignia of domination, the evocative scurry of real people, portrait of the queen Elizabeth and the women sacrificial victim of German resistance group known as the White Rose. Through the interaction of images, Spero is poignant in suggesting - the ceaseless associations of sex, power and violence.

Golub, Spero, Botero, Immendorf and Kiefer base their work on the conventional traditions of western art, to provide a visual language to render their analysis of the copious extent of human catastrophe.