- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

By Dr.Seema Bawa

Willie Bester is arguably South Africa’s best known exponent of the Resistance Art who became a conduit for protest through art forms in the Apartheid period and even after that he continues to raise his voice against violence, corruption, inequality and poverty in South Africa.

Willie Bester is arguably South Africa’s best known exponent of the Resistance Art who became a conduit for protest through art forms in the Apartheid period and even after that he continues to raise his voice against violence, corruption, inequality and poverty in South Africa.

The Apartheid regime in South Africa in 1976, in an attempt to further dis-empower the black majority, insisted that all education would henceforth be in Afrikaans. The Quixotic diktat mandated that these students would take their final examination in Afrikaans too, a language they did not understand. This made school virtually impossible. On the 16th of June 1976 in Soweto when some such students peacefully protested the new act the white police opened fire on them, children, some as young as six, and close to a hundred students were murdered in cold blood.

South African artists of the period responded to the repressive regime through an impassioned distillation of their talent in what is termed Resistance Art. This art covers the entire spectrum mirroring the journey from total deprivation of apartheid to freedom in the country. The top exponents of this art form who depicted the struggle to free the country of Apartheid through artistic expressions in diverse ways include Willie Bester, Jane Alexander, Jonathan Comerford and Helen Sebidi. Art became a pulsating crucible, an exciting and tangible way for these driven souls to express their own and collective aspirations and anguish.

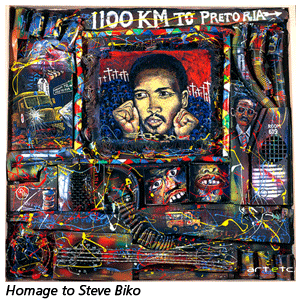

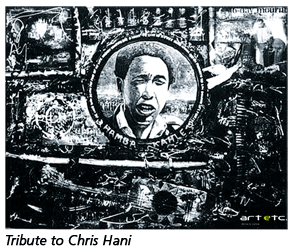

The 1976 Soweto Uprising and the unrest endemic during the 1980s in South Africa impacted Bester. The Community Arts Project Bester attended in 1988 in Cape Town exposed him to creative works by contemporary students that attacked the Apartheid regime. This inspired his initial artworks of protest against the Group Areas Act and the racial composition of the Apartheid Electoral process, that, enabling the white minority (with the most votes) to retain power. The Agit-Prop protest art he was exposed to at the Community Art project changed his oeuvre. At times Bester depicted actual events such as his depiction of the death of Chris Hani, a former leader of the South African Communist Party.

The 1976 Soweto Uprising and the unrest endemic during the 1980s in South Africa impacted Bester. The Community Arts Project Bester attended in 1988 in Cape Town exposed him to creative works by contemporary students that attacked the Apartheid regime. This inspired his initial artworks of protest against the Group Areas Act and the racial composition of the Apartheid Electoral process, that, enabling the white minority (with the most votes) to retain power. The Agit-Prop protest art he was exposed to at the Community Art project changed his oeuvre. At times Bester depicted actual events such as his depiction of the death of Chris Hani, a former leader of the South African Communist Party.

Bester’s oeuvre is predicated on an unobtrusive yet unrelenting epos to reinstate human dignity to the populace degraded by institutionalized racism. His subjects are animate, vigorous and expressive, in contrast to their reduced level of existence.

Willie Bester's subject matter is usually the township scene of South Africa where he spent his years as a child and young adult, and was deeply empathetic to the travails and joys in these cramped quarters. While global media largely depicted negative images of ramshackle shacks, half-clad children and a landscape of debris of refuse in South African townships and unlawful tenant camps; Bester attempts to depict an alternate side of this life. The survivors and the optimistic aspects of township life remain a part of his locus: the vivacity of colour, the wit, the pioneering spirit, the solidarity among the residents and such elements animate his works.

The recurrent motif in his works is depiction of displacement through forced eviction, migrant labour; all mapping the havoc apartheid wreathed on both those who stayed/ fled, on those who resisted / accepted. These themes are intertwined with the materials used in his art. Bester’s works marries the deeply personal with the historical moment. This is evinced in his material that includes the use of newspaper photographs and text to establish the historical moment while photographs that he has taken himself make it more representational, but show that the artist is a part of the environment, and identifies therewith in an observer-participant paradigm. Bester’s transferring a photographic image – (his own or from a newspaper) into oil, onto signages, and found objects lifts the depicted personages or events from their limited spatio-temporal contexts and raises them to Symbolic archetypes of repression or protest.

Bester’s critique of social change is never naive. In a conversation with Dr. Seema Bawa, he addresses issues of corruption and Government accountability in the new South Africa.

Resistance Art

Seema Bawa: What inspired you to use art as the voice of resistance and protest initially against the Apartheid regime and later social unrest?

Willie Bester: It was one of the less violent ways to express myself.

SB: Did this arise from specific incidents and personal experiences, or from the pervasive inequality, exploitation and oppression?

WB: Because of both personal and specific incidents. For example, the killing of Steve Biko, the apartheid laboratory - how people were classified on the basis of their skin colour, the vlakplaas killing fields where dissident’s bodies were disposed of-The Trojan horse and too many to mention. Personal experiences (include) race classification; general racism; police brutality; cradle to grave; system of separation on the basis of skin colour; lack of no existence of basic human rights; group areas acts; separate amenities act and too many (inequities) to mention, both specific and personal experiences feed into my art.

SB: How do you personally and your art relate to other artists in all media, film, theatre and other cultural projects that use culture to register their protest?

WB: It was easy because an umbrella body was established to give a platform to fight the apartheid system on a cultural level and that includes all that was mentioned. As time went, by the oppressed people started to mobilise themselves into pressure groups in the fight against apartheid. The groups consist of some of the following: Labour movements; artists, film, media, poets, dance and theatre; community-based organisations; the international anti-apartheid movements; students' youth organisations and many more. All the organisations that are mentioned formed the umbrella body with the name the MDM which stands for Mass Democratic Movement. And it was under this umbrella that lead to the fall of the apartheid regime.

Political Culture

SB: For you, is there politics of culture? And in this context would you say that your art has evolved and changed with the changes in the political structure. For example the images that you used were individual based in the beginning but one notices now that conceptual aspect has become quite pronounced in your work.

WB: My work does change; depending on the socio-political developments. Just after the fall of the Apartheid, an agreement was reached on a settlement. A new government was formed with some politicians from the previous government. I watched these political developments and I still express myself through my art. (I) give credit where necessary and criticize when it comes to service delivery and corruption and racism wherever it raised its ugly head.

SB: In your opinion considering the wide canvas of your work, as also the attention that your work has received worldwide, have the boundaries of cultural sphere expanded in South Africa?

WB: Yes, it did, but not as one should expect, but we should keep pressurizing those in power.

Trojan Horse

SB: The Trojan Horse1 is one of the most well known pieces, that is connected to a historical event of the Athlone massacre in 1985, it impelled the world to stand up and take notice of the atrocities and their impact on the people of South Africa. Did this response surprise you, or were you always aware of the impact of art on the social and political consciousness of people?

WB: Yes it was a surprise but it came with great difficulties to convince the World at large about the atrocities.

SB: The police had refused you permission to use parts from Kalashnikov sub machine guns to use for your sculpture then. Have the state of affairs changed in post Apartheid period, and artists have more freedom to use materials, given the symbolic and emotional impact that art made out of found material can have on people?

WB: Not many people in government appreciate art, so they would view such a request with great suspicion given our high crime rate. But in our neighbouring countries for instance Mozambique, they do supply artists and sculptors with old sub machine guns to use as material.

SB: The response to your art through the Trojan Art sculpture displayed at the Indian art Fair has been huge. Are you surprised at the response and the sale of the same in India.

WB: No, I was not aware of the Art Fair in India. So it’s difficult to respond to that question.

Language of Protest

SB: Your visual language is made of images of the dispossessed and the dislocated.2 Objects such as guns are easier to understand, but shoes and similar objects form an important part of your visual vocabulary. How did you arrive at this language and its deployment in your works?

WB: The oppressive nature of the apartheid regime and the total lack of freedom of speech and the disregard of Human Rights have forced artists to express themselves in un- conventional ways. The shoes and the other objects refer to daily realities of missing and abuse children and the exploitation and the lack of service delivery.

SB: The use of found objects and materials is noticeable in your works and also in the Willie Bester House. Bicycles, parts of automobiles, plastic are all used and recycled in your works. As a language of protest against political and socio-economic inequities and environment degradation also, how do you choose your materials?

WB: Whatever materials I use in my art, whether in architecture, sculpture or painting should at the end of the day work as an art piece.

Reference

1.Trojan Horse series by Willie Bester refers to the Trojan Horse Massacre. In October 1985, sharply increased tension involving anti-apartheid demonstrators and police in the Cape Town suburb of Athlone precipitated into a conflagration. The apartheid declared a state of emergency in different parts of South Africa. Eleven days into the curfew, the police hidden in the back of a South African Railways truck fired directly into a crowd gathered at an intersection on Thornton Road. Three people ncluding two children were killed, thirteen were injured. An ambush, a shameful act by an armed police against a crowd of around a hundred people led the incident be termed “Trojan Horse Massacre”. The Trojan Horse Massacre, though tiny compared to other dastardly acts, marked a turning point in the struggle against apartheid as it was captured by international media that served to turn global opinion.

Bester created a series of three sculptures to protest the action. Trojan Horse III is the last and most powerful of the series. The work is characterized by an astonishing feel of throbbing vitality and energy and vitality. The sculpture is made from mechanical parts of cars and motorcycles. Bester’s metamorphosis of scrap metal into a truly dynamic and naturalistic animal is a feat unsurpassed. Bester uses a new artistic vocabulary of forms to focus attention on the reification of flesh and blood into de-humanised cogs. Bester originally sought permission from the South African police to use decommissioned Kalashnikov rifles;to signify the smuggling of arms on the African Continent, but he was politely and firmly informed that they were be melted.

2.The main material used also comprises found objects Bester perhaps collected from townships near his home. Willie Bester worked with mixed-media collages using a vast range of materials portraying multiple layers of meaning. Bester painted with oil on photographs which he himself took or extracted from mass media and then combined these elements with superfluous discarded objects from the townships of Cape Town, South Africa. These refuse materials pulsate with rich referentiality and symbolic meaning. Bester creates an alternate artistic idiom and iconography from diverse and unlikely things. Machine parts, old sacking, sticks, various tin cans, sheep bones and wire netting have deep symbolic significance once they become parts of his collage.