- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

The 'Best' Beast

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Sandhya Bordewekar

Communalism in Gujarat, and perhaps all over the country, is like a ghost that cannot seem to be exorcised, returning every now and then, in ever more uglier, ghastlier, nastier forms. The birth-state of the Mahatma continues to pay homage to him by implementing prohibition (on liquor) but his larger, deeper message of brotherhood of mankind appears to be largely brushed under the carpet. Though there have been numerous incidences of communal tension since India's Independence and the partition (1947) that created West and East Pakistan, Gujarat saw its first major communal conflagration in 1969, followed by other incidents now and then through the 1980s, in the early 1990s post the Babri Masjid demolition, and then 2002.

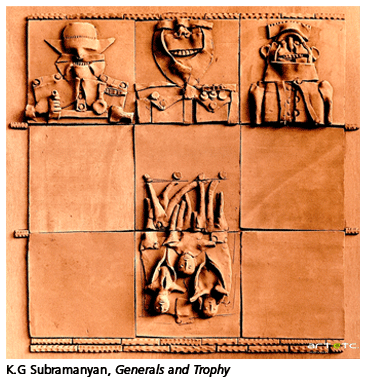

Artists in Baroda have reacted to communal conflicts and the physical, emotional and spiritual wounds that were inflicted on them in many different ways, through their artworks. It is perhaps possible to define these works as 'protesting' against the mindless violence and trying to get people to think about the hopelessness of eternal conflicting. Amongst the powerful works that come to my mind are the terracotta tiles made by K G Subramanyan (Generals and Trophy, 1971, terracotta relief) in response to the military atrocities in Bangladesh's war of independence (1971). Gulammohammed Sheikh's continual referencing of the horrific image of the men atop the Babri Masjid tearing down its domes (1993), in a number of his works over more than 15 years, reveals the depth of the shock, anguish and hurt felt, and signs towards the enormous scale of the communal violence and bitterness it engendered in its wake. In fact, Sheikh's preoccupation with Kabir and his philosophy can also be interpreted as a way of trying to understand, explain and present a possible road ahead, cutting through the centuries-old communal conflict.

Artists in Baroda have reacted to communal conflicts and the physical, emotional and spiritual wounds that were inflicted on them in many different ways, through their artworks. It is perhaps possible to define these works as 'protesting' against the mindless violence and trying to get people to think about the hopelessness of eternal conflicting. Amongst the powerful works that come to my mind are the terracotta tiles made by K G Subramanyan (Generals and Trophy, 1971, terracotta relief) in response to the military atrocities in Bangladesh's war of independence (1971). Gulammohammed Sheikh's continual referencing of the horrific image of the men atop the Babri Masjid tearing down its domes (1993), in a number of his works over more than 15 years, reveals the depth of the shock, anguish and hurt felt, and signs towards the enormous scale of the communal violence and bitterness it engendered in its wake. In fact, Sheikh's preoccupation with Kabir and his philosophy can also be interpreted as a way of trying to understand, explain and present a possible road ahead, cutting through the centuries-old communal conflict.

In the post-2002 communal violence that spread all over Gujarat, a number of artists in Baroda created artworks in response to the actual violence, as well as to the mixed feelings of fury, alienation, impotence, horror, depression. Some of these were displayed in an exhibition organized at the Faculty of Fine Arts Exhibition Hall and sold to create a fund to help people affected by the riots. In the display of the final year under-graduate and post-graduate students of that year, the content of the artworks created mostly dealt with the communal conflict that the students had experienced in some form or another. Most of them were usually literal in the way they were expressed, often 'reaction' triggered mostly centering around media-generated and widely circulated imagery of looting and arson, of mobs with naked swords, burning vehicles and so on. This was understandable considering that they did not have much time to really ruminate upon and think about the content they were dealing with and then dwell on ways to present it in truly powerful forms.

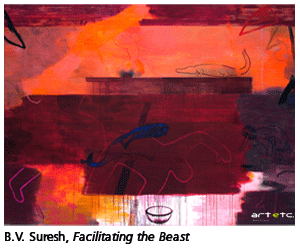

One Baroda artist, however, created a body of work that is amongst the best in terms of its response and as a powerful critique of the 2002 communal riots in Gujarat. It was four years in the making and the artist, B V Suresh, who teaches at the Department of Painting, Faculty of Fine Arts, could not really show it in Baroda. His exhibition of video installation and paintings, Facilitating the Beast was mounted at the Vadehra Gallery in Delhi in 2006. The exhibition was a sensitively modulated and nuanced 'response' to what Suresh saw and experienced during 2002, rather than an impetuous and immediate 'reaction'. It was articulated as a release of bottled-up feelings with which the artist had struggled for more than three years to negotiate, as a trained painter, with ideas and images and then focus on the right image/s to express itself in. The exhibition was designed in two parts. On the first floor of the gallery was a single work -- the video installation, that comprised an installation of sculptural objects with a slow-moving light washing over the installation space at regular intervals, digital prints and video projections. On the second floor were large paintings on canvas as separate units like in a regular gallery show.

One Baroda artist, however, created a body of work that is amongst the best in terms of its response and as a powerful critique of the 2002 communal riots in Gujarat. It was four years in the making and the artist, B V Suresh, who teaches at the Department of Painting, Faculty of Fine Arts, could not really show it in Baroda. His exhibition of video installation and paintings, Facilitating the Beast was mounted at the Vadehra Gallery in Delhi in 2006. The exhibition was a sensitively modulated and nuanced 'response' to what Suresh saw and experienced during 2002, rather than an impetuous and immediate 'reaction'. It was articulated as a release of bottled-up feelings with which the artist had struggled for more than three years to negotiate, as a trained painter, with ideas and images and then focus on the right image/s to express itself in. The exhibition was designed in two parts. On the first floor of the gallery was a single work -- the video installation, that comprised an installation of sculptural objects with a slow-moving light washing over the installation space at regular intervals, digital prints and video projections. On the second floor were large paintings on canvas as separate units like in a regular gallery show.

Suresh zeroed in on the image of bread as one that most evocatively expressed the various levels of interpretations that the exhibition, referring the Best Bakery carnage (see box), should make possible. He also decided to use actual bread loaves rather than their sculptural possibilities in wood, fibre-glass, metal, terracotta and so on. He was okay with the short 'shelf-life' of the traditionally baked bread and experimented with ways of treating its crusted surface after removing the softer inner material so as to make it last longer. Once the artist decided that the object was 'not for selling', it could go beyond being an art object, and that created an unnerving quality of reality about it.

When one looked at the series of bread loaves sitting comfortably on the baking trays, a flood of associations surged immediately in the mind bread as food/staff of life, as a part of everyday life, as the essence of brotherhood of man celebrated through notions of 'breaking bread', as the body of Christ in Biblical terms hence offering both spiritual and physical nourishment, as essentially breakfast fare in India usually accompanied with reading the newspaper with its mediatic manipulations, and so on. As one moved through the exhibition, the innocent loaves, with their dark brown crusts, suddenly began to evoke memories of the charred bodies of Best Bakery as well. In the videos (Retakes of the Shadow, accompanying sound composed by Suresh as well) projected on the wall that ran parallel to the installation, one saw a chilling, savage play of ambiguous shadows. Were these indicating the presence of the killers that the victims saw lurking menacingly through the smoke and fire as they tried to save themselves? Were they ghosts of the already dead? Were they messengers of death, ever-present and waiting for another communal conflagration, to revenge the centuries of a violent history? 41 stills from these videos constituted Shiftings, a series of digital and mixed media works that formed a part of the installation.

As the hazy figures trembled and flashed on the screens, viewers saw themselves, amid the loaves of breads, 'caught' as it were, in the Best Bakery itself, reflected in the strategically mirror-covered opposite wall of the gallery. 'Caught' also, as hundreds of us find ourselves, in the cross-fire of situations where we are vulnerable, where we are in a way responsible for what is happening around us, and where we have not much choice in being able to do anything about them. The viewers therefore were no longer uninvolved visitors to an exhibition, but they implicated in it, whether they liked it or not. It was a master stroke by an artist whose depth of involvement in his subject of exploration took into serious consideration all its myriad possibilities.

In the display of paintings, the thematic focus continued to concentrate on issues of violence and its multiple forms and levels, its use to establish the quality of engagement that one person/group has with another, and thereby to create the contexts for present and future violence. Suresh's work is not the easiest to comprehend. There is a 'sensation of violence not only produced by the actual representation of any single violent event or because of the figures are crouching or sitting in some odd postures. But you can locate the presence of torture or violence even within a seemingly normal figure or event.' (Santhosh S. in Ground under the Feet, interview with B V Suresh, printed in the catalogue to this exhibition.)

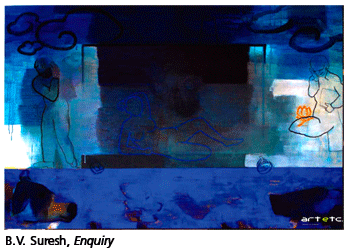

As Deeptha Achar writes in a brilliant essay in the catalogue, Negotiating Visual Fields of the Contemporary, that went with the show, “ … the works do not operate in a modernist frame that yearns for a world where the fragments can be reassembled to make a whole, where meanings are unambiguous, where reality is transparent, uncontested. Instead we are confronted with figures and objects dispersed across the canvas in a narrative without resolution. The eye cannot find meanings hidden behind the symbolic web of the artwork; rather it traverses the artwork to find the play of competing meanings. Figures are produced at the site of violence not through conventional associations tied to a fully fleshed out body but by an evacuation of meaning at the level of the sign and a relocation of violence in the very act of seeing. The reclining nude in Enquiry is clearly open to view, languorous, marked by classical self-composure. However, the hollow, vacant space of the body in outline is locked into display by shutters that are at once backdrop and prison and located in a grid which also holds the cow and the pig, flanked by men who do not spare a glance but who yet hold powers that can 'fix' her in place. Signifying the pornographic gaze, the figure endlessly marks the violence of looking.”

As Deeptha Achar writes in a brilliant essay in the catalogue, Negotiating Visual Fields of the Contemporary, that went with the show, “ … the works do not operate in a modernist frame that yearns for a world where the fragments can be reassembled to make a whole, where meanings are unambiguous, where reality is transparent, uncontested. Instead we are confronted with figures and objects dispersed across the canvas in a narrative without resolution. The eye cannot find meanings hidden behind the symbolic web of the artwork; rather it traverses the artwork to find the play of competing meanings. Figures are produced at the site of violence not through conventional associations tied to a fully fleshed out body but by an evacuation of meaning at the level of the sign and a relocation of violence in the very act of seeing. The reclining nude in Enquiry is clearly open to view, languorous, marked by classical self-composure. However, the hollow, vacant space of the body in outline is locked into display by shutters that are at once backdrop and prison and located in a grid which also holds the cow and the pig, flanked by men who do not spare a glance but who yet hold powers that can 'fix' her in place. Signifying the pornographic gaze, the figure endlessly marks the violence of looking.”

The Best Bakery Carnage

On March 1, 2002, a violent mob of about 500 people attacked a small Muslim-owned bakery, 'Best Bakery', on the outskirts of Baroda. The attack was part of the horrific communal violence that engulfed Gujarat, after the bogie of the Sabarmati Express train was set afire outside Godhra station on February 27 in which Hindu pilgrims from Ayodhya were returning home and in which more than 50 persons were charred to death. At Best Bakery (and the name could not be more ironic), 14 people were killed (12 were Muslims) in the carnage that went on from 6 pm to 10 am the next day. The 'face' of Best Bakery violence was Zaheera Shaikh, then 19 years old, who apparently saw those in the attacking mob responsible for the killings. She recounted what she saw to numerous publications (how the mob were shouting communal slogans, how she and her family fled to the terrace and the first floor room, how the mob set fire to the Bakery). She also filed an FIR, naming the accused. But on March 17, 2003, Zaheera stunned everyone by saying in court she did not see anyone from the mob because she was hiding from it. Subsequently, she changed her statements numerous times, citing threats to her life, intimidation and other pressures and harassment, but it was also alleged that she had taken a huge bribe. For such 'flip-flopping' she was ousted from the Muslim community by the Majlis-e-Shura for 'tarnishing the community's image', and sentenced by the Supreme Court to one year in prison and Rs. 50,000 for perjury.

On March 1, 2002, a violent mob of about 500 people attacked a small Muslim-owned bakery, 'Best Bakery', on the outskirts of Baroda. The attack was part of the horrific communal violence that engulfed Gujarat, after the bogie of the Sabarmati Express train was set afire outside Godhra station on February 27 in which Hindu pilgrims from Ayodhya were returning home and in which more than 50 persons were charred to death. At Best Bakery (and the name could not be more ironic), 14 people were killed (12 were Muslims) in the carnage that went on from 6 pm to 10 am the next day. The 'face' of Best Bakery violence was Zaheera Shaikh, then 19 years old, who apparently saw those in the attacking mob responsible for the killings. She recounted what she saw to numerous publications (how the mob were shouting communal slogans, how she and her family fled to the terrace and the first floor room, how the mob set fire to the Bakery). She also filed an FIR, naming the accused. But on March 17, 2003, Zaheera stunned everyone by saying in court she did not see anyone from the mob because she was hiding from it. Subsequently, she changed her statements numerous times, citing threats to her life, intimidation and other pressures and harassment, but it was also alleged that she had taken a huge bribe. For such 'flip-flopping' she was ousted from the Muslim community by the Majlis-e-Shura for 'tarnishing the community's image', and sentenced by the Supreme Court to one year in prison and Rs. 50,000 for perjury.

The Best Bakery case, along with picture of Qutubuddin Ansari, a tailor from Ahmedabad, whose poignant image -- weeping, with folded hands, begging for mercy ultimately became one of the most haunting and lasting memories of the riots. What happened with Zaheera or what she did to herself has also become symbolic of the highly complex socio-economic forces that swing into operation before, during and after communal violence in a democratic political set-up that can severely hamper the judicial process and cause painful delays in its delivery.