- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Mapping the Conscience...

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Ina Puri

“All memory is individual, unreproducible – it dies with each person. What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds. Ideologies create substantiating archives of images, representative images, which encapsulate common ideas of significance and trigger predictable thoughts, feelings.”

-Susan Sontag

Seldom was Manjit Bawa’s art associated with ideologies or even histories chronicling his times, the colour saturated canvases seeming to celebrate a mythic world instead, where the gods enthralled herds of cows and buffaloes with their flutes while the luminous sun lit up the surroundings in shades of brilliant green.

Elsewhere, the painter had drawn inspiration from Puranic tales and the epics, painting purple tigers against cadmium yellow backdrops, creating a pictorial utopia where the meek and the mighty could co-exist in peaceful union, deliberately disregarding the harsher realities of the existing world. A practitioner of Sufi philosophy, his worldview drew upon the hope that one day, peace would reign.

While this was partly true, especially in the context of his later years, the truth of the matter was somewhat different. From the very beginning, even way back in the early ‘70s in London, the artist was an active participant in the racial discrimination movement when Asian migrants were exploited by contractors because the impoverished men were desperate to eke out a living at any cost. The clandestine meetings in dim basements were conducted at great personal risk but in the end, their voices were heard and the migrants finally found representation; their cases given a fair hearing.

While this was partly true, especially in the context of his later years, the truth of the matter was somewhat different. From the very beginning, even way back in the early ‘70s in London, the artist was an active participant in the racial discrimination movement when Asian migrants were exploited by contractors because the impoverished men were desperate to eke out a living at any cost. The clandestine meetings in dim basements were conducted at great personal risk but in the end, their voices were heard and the migrants finally found representation; their cases given a fair hearing.

In later years, too, Manjit was ready to protest against any kind of injustice, standing up for the cause of freedom and justice. When religious fundamentalists struck in Ayodhya demolishing the Babri Masjid, Manjit was an eyewitness, who saw the bigots raze the structure to the ground, all the while raising slogans in praise of Lord Rama. In his story for The Illustrated Weekly, Manjit wrote his account of the horrific assault and made sketches of the crumbling edifice, with a poignant twist, showing Hanuman fleeing the ravaged site of ‘Ram Janmabhoomi’. He addressed meetings and conclaves seeking support of the common man, pleading that sanity must prevail before the nation succumbs to the ranting of the fundamentalists. He risked his own safety in the process when the bigots turned their attention to him, threatening to attack his studio where he had, according to their claims, painted Hindu goddesses in the nude (rings a bell?)!

Undeterred, Manjit had gone ahead with his stand and from his sketches, painted a canvas of Hanuman abandoning the burning Ayodhya, sharing the story of his experience with viewers.

Undeterred, Manjit had gone ahead with his stand and from his sketches, painted a canvas of Hanuman abandoning the burning Ayodhya, sharing the story of his experience with viewers.

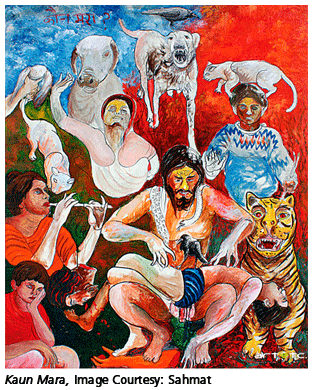

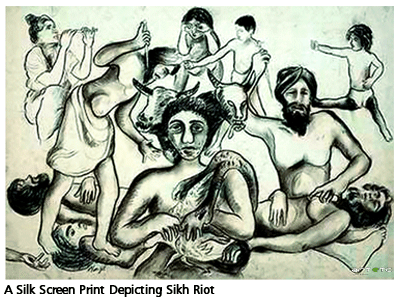

Despite these aberrations that left him angry, upset and anguished, Manjit was at heart a peace-loving man, reluctant to give up on life. It was therefore, with great trepidation that I requested him to a show that drew upon his grim memories of the Sikh Riots that had left a community of people orphaned and distraught. Mapping the Conscience (1984-2004) was thus the only time that Manjit exhibited a body of work that introspected on a time when the nation’s security forces brutally maimed, tortured and killed innocent men, women and children to avenge the crime of one security guard who had turned his gun on the country’s Prime Minister.

Remembering that time was difficult for Manjit as it triggered off a series of recollections that still haunted him; often waking him up in the middle of the night as he recalled the black smoke coiling up in the skies, the heart-breaking screams of the widows, children as they recognised a familiar face in the pile of dead.

While the paintings, almost allegorical, excavated for Manjit some aching memories, he was already moving on, determined that his voice protesting against the injustices be heard. He had to live another day, pick up the brush and start working on the incomplete painting awaiting him in his studio.