- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Protest Art in China

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

by Nalini S Malaviya

Faced with demolition of art villages and severe governmental policies including clampdowns on freedom of speech, artists in China resort to activism in order to have their voices heard...

To discuss art in China, particularly protest art, it is essential to contextualise it in terms of its turbulent history, government policies, the prevailing social and political environment and the functioning of the artist amidst these confines. Going back to the 1960s, the cultural revolution in China caused a socio-political upheaval that lasted for about a decade and had major repercussions on the existing and future arts and culture scenario as it resulted in large scale destruction of art and artefacts in an effort to obliterate remnants of cultural history. It encouraged the creation of art according to newly issued government directives as Mao Zedong, the political leader set out to establish a new social and political system in China with an objective to communicate and enforce a new set of ideologies, essentially adopting a propagandist approach through arts. As a result, a socialist realist style depicting revolutionary subjects such as workers, soldiers and peasants were favoured in comparison to conventional themes such as landscapes. This particular phase is highly relevant from our perspective of discussing protest art in China as it had a major impact on artists, especially traditional painters who were publicly humiliated and tortured. The mass persecution that continued during this phase remains shrouded in obscurity and controversy due to lack of adequate documentation and sustained efforts by the Chinese government. As a consequence, in countries outside China there remains ample inaccuracies and ambiguity in the reading of Chinese art. Also, most of the information which is available for public consumption stems from Western media, which again is often perceived to be biased and perhaps rather subjective. This has been one of the major challenges in sifting through and collating information for this article.

However, from what one has gathered it appears that the survival of art and artists in China has been directly proportional to the alignment of the subject matter with the ideologies of the ruling political party, for instance pro-communist party beliefs have been a reason for continued sustenance whereas an anti-State stance could result in a‘re-education’ program forcing the artists to become farmers. Lack of a conducive liberal environment, a propagandist attitude and a paranoia related to the creative fields continues to afflict contemporary art in China. With this background it is a little easier to obtain an insight into Chinese contemporary art and mainly protest art, but on the other hand China’s dominance in the international art market (indicated by recent market analyses reports) may appear paradoxical.

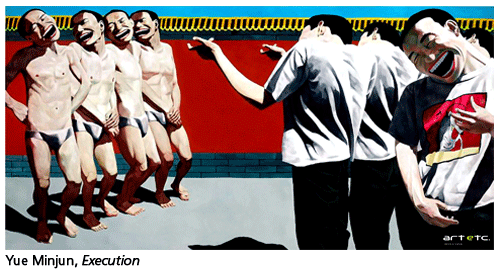

It appears that fear of the government is so pervasive that several Chinese artists who have depicted violent scenes from Tiananmen Square or other atrocities in an effort to raise their voices in dissent eventually end up denying that their art is a form of protest or criticism of the government. The tendency is to attribute the source of inspiration to a wider global phenomena rather than a specific event in China, which in fact they may have either witnessed or even participated in. For instance, the painting Execution by artist Yue Minjun is believed to be inspired by the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and is amongst the most expensive work sold by a Chinese contemporary artist, yet, the artist refuses to accept Tiananmen episode as the sole source for his work. Incidentally, Execution has been compared to several historically significant paintings symbolic of protest, such as The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya which commemorates the Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s armies, the Execution of Maximilian by Edouard Manet a series of paintings depicting the execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico and the Massacre in Korea by Pablo Picasso believed to be a criticism of American intervention in the Korean War.

It appears that fear of the government is so pervasive that several Chinese artists who have depicted violent scenes from Tiananmen Square or other atrocities in an effort to raise their voices in dissent eventually end up denying that their art is a form of protest or criticism of the government. The tendency is to attribute the source of inspiration to a wider global phenomena rather than a specific event in China, which in fact they may have either witnessed or even participated in. For instance, the painting Execution by artist Yue Minjun is believed to be inspired by the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and is amongst the most expensive work sold by a Chinese contemporary artist, yet, the artist refuses to accept Tiananmen episode as the sole source for his work. Incidentally, Execution has been compared to several historically significant paintings symbolic of protest, such as The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya which commemorates the Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s armies, the Execution of Maximilian by Edouard Manet a series of paintings depicting the execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico and the Massacre in Korea by Pablo Picasso believed to be a criticism of American intervention in the Korean War.

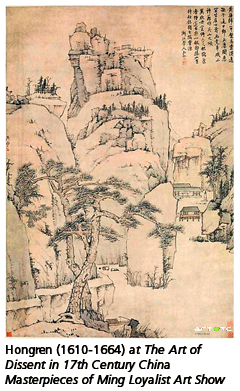

A recent exhibition, The Art of Dissent in 17th Century China Masterpieces of Ming Loyalist Art from the Chih Lo Lou Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art curated by Maxwell K. Hearn brought together landscape paintings and calligraphies by the leading artists of the time. According to historical data, the Ming dynasty from the 14th to the 17th century was followed by the conquest of China by semi-nomadic Manchu tribesmen and was marked by intense strife and conflict in the country’s history. However, these paintings appear beguiling with no overt signs of violence or protests, even though this was a period of intense chaos and trauma for China. Holland Cotter writes in the New York Times, “Some, like Xiao Yuncong (1591-1669), devised subtle emblems of protest and mourning. His Ink Plum depicts a single plum tree, a symbol of ethical purity, as little more than a graceful but insubstantial twig. It floats unplanted in midair, as if it had been chopped off at the bottom or torn away from its roots.” Incidentally, it was also a phase of heightened creativity where art was often used as an outlet for protest. The artworks in this exhibition corroborate that protest art has existed in China for centuries, although there might be variances in the forms of expression. As art and politics continues to remain intertwined, there are many contemporary artists who are increasingly resorting to social activism in a bid to raise their voices against the government, for instance Ai Weiwei and Wu Yuren, are some of the well-known artists’ activists in China. Their efforts at organising support for causes related to arts as well as socially relevant issues have helped in generating international support and interest. At this juncture, it is relevant to reiterate once again that access to information pertaining to art and artists in China is limited and heavily censored. It is difficult to verify or authenticate facts, cross check polarity of viewpoints or obtain a true real time picture.

A recent exhibition, The Art of Dissent in 17th Century China Masterpieces of Ming Loyalist Art from the Chih Lo Lou Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art curated by Maxwell K. Hearn brought together landscape paintings and calligraphies by the leading artists of the time. According to historical data, the Ming dynasty from the 14th to the 17th century was followed by the conquest of China by semi-nomadic Manchu tribesmen and was marked by intense strife and conflict in the country’s history. However, these paintings appear beguiling with no overt signs of violence or protests, even though this was a period of intense chaos and trauma for China. Holland Cotter writes in the New York Times, “Some, like Xiao Yuncong (1591-1669), devised subtle emblems of protest and mourning. His Ink Plum depicts a single plum tree, a symbol of ethical purity, as little more than a graceful but insubstantial twig. It floats unplanted in midair, as if it had been chopped off at the bottom or torn away from its roots.” Incidentally, it was also a phase of heightened creativity where art was often used as an outlet for protest. The artworks in this exhibition corroborate that protest art has existed in China for centuries, although there might be variances in the forms of expression. As art and politics continues to remain intertwined, there are many contemporary artists who are increasingly resorting to social activism in a bid to raise their voices against the government, for instance Ai Weiwei and Wu Yuren, are some of the well-known artists’ activists in China. Their efforts at organising support for causes related to arts as well as socially relevant issues have helped in generating international support and interest. At this juncture, it is relevant to reiterate once again that access to information pertaining to art and artists in China is limited and heavily censored. It is difficult to verify or authenticate facts, cross check polarity of viewpoints or obtain a true real time picture.

Several protest movements have been organized around eviction and demolition of artist settlements in China – one of the primary concerns that artists face in today’s scenario. Evictions of artists from artists’ villages despite lease periods remaining have been a common occurrence in China, especially in the last few years. There have been virtually no notice periods and the artists have not been allowed sufficient time to make alternate arrangements. The Beijing International Art Camp - Suo Jia Cun in Beijing was demolished in 2005, the Zhengyang Creative Art Zone in Jinzhan village, in Chaoyang district in 2010 and the 696 Weihai Road complex faced eviction last year. In many of these cases the artists and their families have been assaulted and injured requiring hospitalization. Such events which have increased in frequency have triggered artists and supporters to come out in large numbers to protest against eviction and use of brutal force. In an effort to save their studios and living spaces, and also to save other art districts which may come under the crusher ball soon, there have been several initiatives to highlight their fragile status.

Several protest movements have been organized around eviction and demolition of artist settlements in China – one of the primary concerns that artists face in today’s scenario. Evictions of artists from artists’ villages despite lease periods remaining have been a common occurrence in China, especially in the last few years. There have been virtually no notice periods and the artists have not been allowed sufficient time to make alternate arrangements. The Beijing International Art Camp - Suo Jia Cun in Beijing was demolished in 2005, the Zhengyang Creative Art Zone in Jinzhan village, in Chaoyang district in 2010 and the 696 Weihai Road complex faced eviction last year. In many of these cases the artists and their families have been assaulted and injured requiring hospitalization. Such events which have increased in frequency have triggered artists and supporters to come out in large numbers to protest against eviction and use of brutal force. In an effort to save their studios and living spaces, and also to save other art districts which may come under the crusher ball soon, there have been several initiatives to highlight their fragile status.

For instance, last year, artists in Shanghai organized a protest inspired by Dorothy and Toto’s odyssey in the Land of Oz – a Wizard of Oz themed protest which was launched under the direction of Zhang Li Ping, the curator of the Shanghai Biennial. Over 30 artists based at the 696 Weihai Road complex faced with an eviction mounted a media campaign which eventually granted them some reprieve. In another incident, which is more of a commentary on the situation rather than protest art per se, a Portuguese street artist Alexander Farto also called Vhils started carving portraits of evicted tenants as murals on walls of buildings and homes shortly before they were demolished. Working with the same tools, hammers and chisels which are used for the purpose of demolition, his works have been evoking a mixed response where there are some positive sentiments amidst abundant resentment to a foreign artist’s comment on China’s internal politics. On the other hand, two decades after the Tiananmen Square incident, artist Chen Guang who was a 17 year old soldier at the time, organized an art exhibition which focuses on the ill famed episode that resulted in the killing of hundreds of people and injured many more. The series of paintings are based on hundreds of photographs which he took at Tiananmen Square and when local galleries refused to display his art, Guang posted them on the Internet but the images were taken down within hours. Another example of active censorship! Despite repeated warnings from government officials, Guang finally succeeded in exhibiting his paintings in 2009. As is widely known, Tiananmen Square remains a sensitive and taboo subject and any talk about it is actively discouraged. However, more and more artists in China have been voicing their protest through various means such as installations, performances, video art, photography and by organizing campaigns through slogans, processions and marches. These are being organized in China and also in several major cities across the world, the latter of course being much easier to implement.

Continuing back to the issue of evictions faced by artists, it is evident that massive urbanization plans by the government are one of the major reasons for the demolition of several art districts which are situated in suburban parts of main cities. The residents of the Zhengyang Creative Art Zone in Jinzhan village were served notices in 2009 – 10 and as a result artist Xiao Ge organized a series of collective events and exhibitions titled ‘Warm Winter’ by mobilizing about twenty art zones. Huang Rui, a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and one of the first artists to move his studio into the 798 Art District in 2002, staged a performance, wearing a black and white costume printed with the word ‘China’ and the Chinese characters chai na (meaning to demolish and remove), playing with their similar sounding homophonics. Wu Yiqiang an artist from Dongying Art District, another art community under threat, decided upon a performance where he lay naked against the ruins of cold buildings braving freezing temperatures.

Liu Bolin

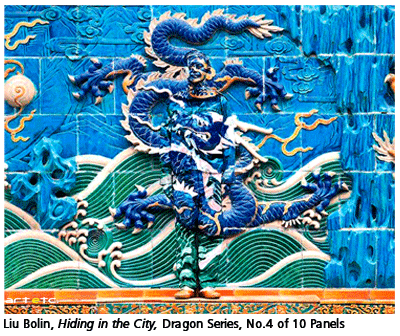

In 2006 Liu Bolin, a prominent Chinese contemporary artist inspired by the Chinese government’s demolition of the Suo Jia Cun Artist Village in Beijing camouflaged himself in the series of photographs, Hiding in the City by painting himself as part of the urban landscape. Bolin has become famous as the invisible man after he decided to use his art as a means of silent protest. Using his own body to paint himself and merge into various urban settings in Beijing, Bolin attempts to comment on the fragile status of artists and their living conditions. Involved heavily with social issues, Bolin has been trying to draw attention to the problems arising as a result of fast paced economic development which is often random and even whimsical. In Hiding in the City, he used slogans (a common tool used by communist parties) as a means to reinforce and review the messages on the slogan. He painted his body into some of the slogans to force the viewer to reconsider and reread not only the slogan but also his individual circumstances. In another series, titled Shadow, Bolin tried to merge with the flat surfaces while it was raining. As he moved away, the dry surface with the human outline disappeared in an instant demonstrating the helplessness and inevitability of human life faced with environmental forces. Bolin’s form of protest, a silent and muted approach which some have termed ‘gimmicky’ has nevertheless generated a lot of interest both within China and abroad.

In 2006 Liu Bolin, a prominent Chinese contemporary artist inspired by the Chinese government’s demolition of the Suo Jia Cun Artist Village in Beijing camouflaged himself in the series of photographs, Hiding in the City by painting himself as part of the urban landscape. Bolin has become famous as the invisible man after he decided to use his art as a means of silent protest. Using his own body to paint himself and merge into various urban settings in Beijing, Bolin attempts to comment on the fragile status of artists and their living conditions. Involved heavily with social issues, Bolin has been trying to draw attention to the problems arising as a result of fast paced economic development which is often random and even whimsical. In Hiding in the City, he used slogans (a common tool used by communist parties) as a means to reinforce and review the messages on the slogan. He painted his body into some of the slogans to force the viewer to reconsider and reread not only the slogan but also his individual circumstances. In another series, titled Shadow, Bolin tried to merge with the flat surfaces while it was raining. As he moved away, the dry surface with the human outline disappeared in an instant demonstrating the helplessness and inevitability of human life faced with environmental forces. Bolin’s form of protest, a silent and muted approach which some have termed ‘gimmicky’ has nevertheless generated a lot of interest both within China and abroad.

Wu Yuren

It’s Coming, was the unusual title of an exhibition organized by Wu Yuren in 2010. A photographer, installation artist and political activist involved with the rights protection movement, Yuren’s objective was also to draw attention to the random and swift destruction of the city’s art districts. The title of the exhibition It’s Coming is based on the several SMS messages his friend sent him regarding the approach of the bulldozers and the demolition mob. Earlier that same year, Yuren had organized a march in Beijing to protest against the government’s attempts to target art settlements. In an interview he mentioned that this particular exhibition was a reflection of the current situation in China, especially its cultural environment where the ideology had become increasingly restrictive. He said, “An artist’s creativity and liberty is limited as we have less and less space for free speech. And now they’re even trying to destroy the art districts — the places where we live and work.” The installation that he created comprised of a phone in the gallery which gave off an alarm every minute as a reminder to the current living environment. In another incident involving police atrocities on artists, Wu Yuren organized a group of artists to protest. He also transformed White Box Museum of Art into a large demolition site; however there is very little information available on that installation. The only text available informs – ‘The growth of an artist is a continuous process of self-discovery, and going beyond the self’. Although the protest was fairly successful and managed to get a compensation package for the artists, Wu Yuren was soon arrested on multiple charges. Later when Yuren was released after spending considerable time in prison, Ai Weiwei was arrested on charges that included plagiarism, tax evasion and pornography amongst others. No discourse on Chinese contemporary art and particularly protest art can be complete without a mention of Ai Weiwei who is one of the most prominent Chinese artists in the international arena. A staunch political activist, Weiwei has been campaigning for democracy and human rights in China and has courted many controversies in his long career. Ai Weiwei’s work has been provocative and has needled the Chinese government time and again. When Weiwei was arrested last year, artists and activists from all over the world planned a protest which was inspired by Ai Weiwei’s 2007 Fairytale project in Kassel, Germany. In his Fairytale project, Weiwei had installed a set of 1001 Ming and Qing dynasty chairs in Kassel, one for each of the 1001 Chinese travellers he also brought to Germany to symbolize displacement and to represent the rapidly altering Chinese identity. 1001 Chairs for Ai Weiwei was based along similar lines and involved sitting peacefully in chairs at Chinese embassies and consulates across the globe in support of the artist. A New York City’s Creative Time initiative, the organization stated, “1001 Chairs for Ai Weiwei calls for [Ai's] immediate release, supporting the right of artists to speak and work freely in China and around the world.” The well intended gesture unfortunately did not garner as much support as was expected, at least not on a worldwide scale despite the use of social media. Weiwei was released in June last year with restrictions on his movement and with instructions on refraining from making any political statements.

It’s Coming, was the unusual title of an exhibition organized by Wu Yuren in 2010. A photographer, installation artist and political activist involved with the rights protection movement, Yuren’s objective was also to draw attention to the random and swift destruction of the city’s art districts. The title of the exhibition It’s Coming is based on the several SMS messages his friend sent him regarding the approach of the bulldozers and the demolition mob. Earlier that same year, Yuren had organized a march in Beijing to protest against the government’s attempts to target art settlements. In an interview he mentioned that this particular exhibition was a reflection of the current situation in China, especially its cultural environment where the ideology had become increasingly restrictive. He said, “An artist’s creativity and liberty is limited as we have less and less space for free speech. And now they’re even trying to destroy the art districts — the places where we live and work.” The installation that he created comprised of a phone in the gallery which gave off an alarm every minute as a reminder to the current living environment. In another incident involving police atrocities on artists, Wu Yuren organized a group of artists to protest. He also transformed White Box Museum of Art into a large demolition site; however there is very little information available on that installation. The only text available informs – ‘The growth of an artist is a continuous process of self-discovery, and going beyond the self’. Although the protest was fairly successful and managed to get a compensation package for the artists, Wu Yuren was soon arrested on multiple charges. Later when Yuren was released after spending considerable time in prison, Ai Weiwei was arrested on charges that included plagiarism, tax evasion and pornography amongst others. No discourse on Chinese contemporary art and particularly protest art can be complete without a mention of Ai Weiwei who is one of the most prominent Chinese artists in the international arena. A staunch political activist, Weiwei has been campaigning for democracy and human rights in China and has courted many controversies in his long career. Ai Weiwei’s work has been provocative and has needled the Chinese government time and again. When Weiwei was arrested last year, artists and activists from all over the world planned a protest which was inspired by Ai Weiwei’s 2007 Fairytale project in Kassel, Germany. In his Fairytale project, Weiwei had installed a set of 1001 Ming and Qing dynasty chairs in Kassel, one for each of the 1001 Chinese travellers he also brought to Germany to symbolize displacement and to represent the rapidly altering Chinese identity. 1001 Chairs for Ai Weiwei was based along similar lines and involved sitting peacefully in chairs at Chinese embassies and consulates across the globe in support of the artist. A New York City’s Creative Time initiative, the organization stated, “1001 Chairs for Ai Weiwei calls for [Ai's] immediate release, supporting the right of artists to speak and work freely in China and around the world.” The well intended gesture unfortunately did not garner as much support as was expected, at least not on a worldwide scale despite the use of social media. Weiwei was released in June last year with restrictions on his movement and with instructions on refraining from making any political statements.

Even as several Chinese artists continue to lobby for social and political reforms amidst debates and controversies, recent market reports belie all of that and Chinese contemporary art stands strong in the global art market.

Bibliography

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liu_Bolin

http://hyperallergic.com/22764/ai-weiwei-protest/

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Chinese-artists-fight-studio-eviction/23355

http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/67/MassEvictionOfBeijingArtists

http://shanghaiist.com/2012/02/13/photos_vhils_in_shanghai.php#photo-1

http://www.businessinsider.com/vhils-portraits-shanghai-2012-2?nr_email_referer=1#ixzz1nZkfbddk

http://hk.asia-city.com/events/article/upclose-wu-yuren

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/world/asia/18beijing.html

http://mlartsource.com/blog/57/some-years-installation-by-wu-ren

http://www.chinapost.com.tw/china/national-news/2011/04/07/297731/Chinese-artist.htm

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/24/world/asia/24china.html? _r=1