- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Guerrilla Girls: The Masked Culture Jammers of the Art World

- Creating for Change: Creative Transformations in Willie Bester’s Art

- Radioactivists -The Mass Protest Through the Lens

- Broot Force

- Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

- Revisiting Art Against Terrorism

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- In the Summer of 1947

- Mapping the Conscience...

- 40s and Now: The Legacy of Protest in the Art of Bengal

- Two Poems

- The 'Best' Beast

- May 1968

- Transgressive Art as a Form of Protest

- Protest Art in China

- Provoke and Provoked: Ai Weiwei

- Personalities and Protest Art

- Occupy, Decolonize, Liberate, Unoccupy: Day 187

- Art Cries Out: The Website and Implications of Protest Art Across the World

- Reflections in the Magic Mirror: Andy Warhol and the American Dream

- Helmut Herzfeld: Photomontage Speaking the Language of Protests!

- When Protest Erupts into Imagery

- Ramkinkar Baij: An Indian Modernist from Bengal Revisited

- Searching and Finding Newer Frontiers

- Violence-Double Spread: From Private to the Public to the 'Life Systems'

- The Virasat-e-Khalsa: An Experiential Space

- Emile Gallé and Art Nouveau Glass

- Lekha Poddar: The Lady of the Arts

- CrossOver: Indo-Bangladesh Artists' Residency & Exhibition

- Interpreting Tagore

- Fu Baoshi Retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Random Strokes

- Sense and Sensibility

- Dragons Versus Snow Leopards

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, February – March 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, March, 2012 – April, 2012

- In the News, March 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Reza Aramesh: Action X, Denouncing!

Issue No: 27 Month: 4 Year: 2012

Franck Barthalemy writes on Reza Aramesh, an Iranian artist

He was born in Ahwaz in 1970. At sixteen, in the midst of the Iran-Iraq conflict, he left his country to try his luck somewhere else where people would be more open- minded and free. Like many others, he had the USA in mind. He stopped in London. He studied a bit of chemistry before joining the Goldsmiths College. Reza is a photographer. He explores the various representations of conflicts and shows the viewers the unseen. Not the blood and the guns, the bodies and the soldiers, but the rest. When one sees a photo by Aramesh, one cannot forget it. I saw my first one at the Art Brussels in 2011 and it is still stuck in my memory. What a photo it was! For its size, I virtually walked into it: three panels, human size, 190x73 cm, 190x92 cm and 190x73 cm. For the location of the shot: The Hall of Mirrors, Versailles Palace. For its subject: sitting migrant-like workers in the opulence of a stateroom. For the emotions it transpires through the gaze of the figures. For its provoking title: Action 108. Palestinians Wait to Cross the Erez Crossing. 20th June 2007. For its air de déjà vu.

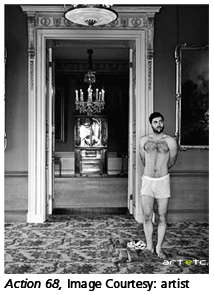

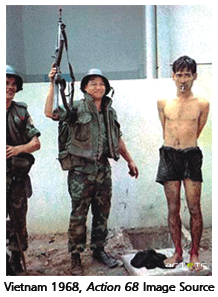

Reza is an observer. He looks at the world through images of conflicts. Whether it is Vietnam, Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Algeria or Korea, he scouts for war photographs in the press and on the net. He finds thousands of them. What do they have in common? Why are the viewers not disturbed by them anymore? They are violent. They are bloody. They show dead people. They display weapons. And nobody seems to see them. Reza studies them carefully. He analyses every composing elements. It happens that very often they show a victim and a victimizer, power and submission. They show people suffering. The artist made it a speciality to de-construct the shots in order to re-construct them and reveal the unseen. Reza replays the historical scene. He chooses a venue. He picks up non professional models. He removes all references to terror. He reframes the shot. In Action 68, Kenwood house in London becomes Ton Son Nhut airbase in Vietnam. The South Vietnamese armed soldiers have disappeared to let the Vietcong prisoner's avatar alone, standing in the same half naked attire, his clothe at his feet. The fear one can feel on the prisoner's face has become an empty stare. While removing the iconic elements of the conflict, Reza reveals the victim's dignity. He makes the viewers focus on the emotion of the instant. He invites the viewers to the intimacy of the scene. Nudity of the model helps creating a close relationship between the seen and the seeing and forces the viewers to unveil another screaming opposition between wealth and poverty. The opulence of the place offers a challenging contrast with the nude body of the model. Reza reminds us the poor help building the wealth of the rich. In this process, the powerful do not suffer, but the powerless do. As a consequence of the restaging, and perhaps as a moral of it, the artist juxtaposes the beauty of the model and the beauty of the place.

Reza is an observer. He looks at the world through images of conflicts. Whether it is Vietnam, Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Algeria or Korea, he scouts for war photographs in the press and on the net. He finds thousands of them. What do they have in common? Why are the viewers not disturbed by them anymore? They are violent. They are bloody. They show dead people. They display weapons. And nobody seems to see them. Reza studies them carefully. He analyses every composing elements. It happens that very often they show a victim and a victimizer, power and submission. They show people suffering. The artist made it a speciality to de-construct the shots in order to re-construct them and reveal the unseen. Reza replays the historical scene. He chooses a venue. He picks up non professional models. He removes all references to terror. He reframes the shot. In Action 68, Kenwood house in London becomes Ton Son Nhut airbase in Vietnam. The South Vietnamese armed soldiers have disappeared to let the Vietcong prisoner's avatar alone, standing in the same half naked attire, his clothe at his feet. The fear one can feel on the prisoner's face has become an empty stare. While removing the iconic elements of the conflict, Reza reveals the victim's dignity. He makes the viewers focus on the emotion of the instant. He invites the viewers to the intimacy of the scene. Nudity of the model helps creating a close relationship between the seen and the seeing and forces the viewers to unveil another screaming opposition between wealth and poverty. The opulence of the place offers a challenging contrast with the nude body of the model. Reza reminds us the poor help building the wealth of the rich. In this process, the powerful do not suffer, but the powerless do. As a consequence of the restaging, and perhaps as a moral of it, the artist juxtaposes the beauty of the model and the beauty of the place.

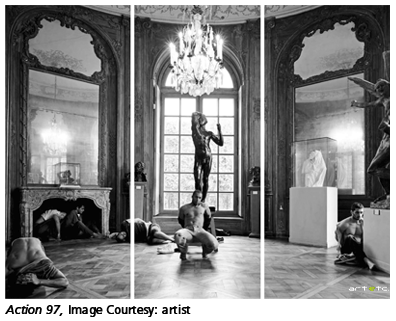

While looking at Reza's photographs, the viewers can be drawn into older memories. The artist not only uses photographic images that have circulated widely as his main source of inspiration, but he composes his shots consciously referring to very famous master pieces. In Action 97, shot at the Rodin Museum in Paris, the artist replays a scene from the Franco-Algerian conflict of the 50s. The main protagonist squats in front of the Rodin historical black bronze L'âge d'Airain, his half removed sweater keeping his hands tied at his back. He is muscular, bear chest. His position reminds us the Belvedere Torso, a nude male white marble kept at the Vatican. The artist does not leave anything to the chance. Each position is carefully studied and demonstrates how the artist can be at ease with old and modern imagery. This rare ability allows him to deal with a beautiful balance between beauty and terror in the same shot. The equilibrium is perhaps reinforced by the only presence of male models, half nude, fit and young. It brings a gay erotic dimension and along with it a surreal sensitivity. It creates an all the more closer relationship between the viewers and the art work, a sort of unsaid secret. Carravagio, another key reference for the artist, was a master in showing the unsaid.

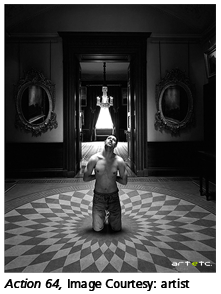

Reza brings the war scenes in the homes of rich owners. He brings inside what belongs to public space. He breaks the peace of the home with the noise of the war. He makes a clear connection between war and wealth. Those who die are not those who own. He once said “war is about money, power and greed”1. When he sets his model in Action 64, Reza creates a martyr in Kenwood House, London. He is kneeling right in the middle of a rosette tile looking up, detached from the reality. Reza urges the viewers to live the scene. He offers them the role of the victimizers. He transforms them into the victors. He plays admirably the questioner: can you, you the viewer, be a victimizer? The question is doubly disturbing that the victim is divinely beautiful. The viewer empathizes with the victim at the same time holds the sword. There is no visible source of violence but the violence is so present. In order to confuse the viewer even more, the artist makes his photographs in black & white. The viewer cannot date them. The viewer cannot locate them. The viewer can identify him/her self with the victimizer or the victim easily.

Reza brings the war scenes in the homes of rich owners. He brings inside what belongs to public space. He breaks the peace of the home with the noise of the war. He makes a clear connection between war and wealth. Those who die are not those who own. He once said “war is about money, power and greed”1. When he sets his model in Action 64, Reza creates a martyr in Kenwood House, London. He is kneeling right in the middle of a rosette tile looking up, detached from the reality. Reza urges the viewers to live the scene. He offers them the role of the victimizers. He transforms them into the victors. He plays admirably the questioner: can you, you the viewer, be a victimizer? The question is doubly disturbing that the victim is divinely beautiful. The viewer empathizes with the victim at the same time holds the sword. There is no visible source of violence but the violence is so present. In order to confuse the viewer even more, the artist makes his photographs in black & white. The viewer cannot date them. The viewer cannot locate them. The viewer can identify him/her self with the victimizer or the victim easily.

Reza's photographs are refined and subtle. They are never aesthetically correct though well charged with emotions, pain, sorrow and despair. They carry a clear message without blood and tears. The artist protests the greed of the politicians who create conflicts. He protests the violence deployed to own. He protests the waste of lives. He challenges the interchangeable victim/victimizer role. He questions the never ending cycle.

Reza Aramesh creates art works that keep us alert. His photographs are the reminders every citizen of the world should keep exposed to make the world a better place.